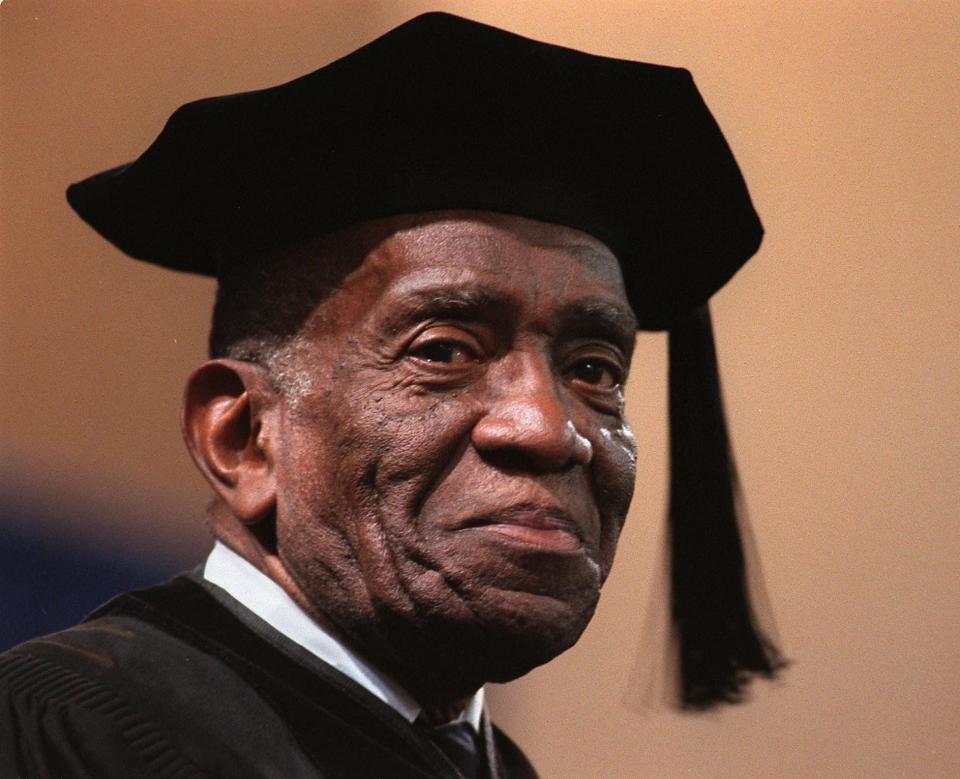

'An upstanding man': The formerly enslaved Savannah man who ignited W.W. Law's love of history

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Albert Oetgen is a retired journalist. He worked as a reporter for the Savannah Morning News from 1976-1980, and also reported for newspapers in Richmond, Virginia, and Tallahassee, Florida. He served as a producer for ABC World News Tonight, NBC and CBS Evening News. He is working on a biography of Savannah civil rights icon W. W. Law.

Slavery was a central theme in W.W. Law’s pioneering efforts to chronicle the history of Savannah’s African American community. As an adult, he read extensively on the topic.

But the Civil Rights Movement leader’s knowledge of slavery was by no means limited to books. His knowledge of slavery was rooted in his early childhood.

It began with Abraham Barnard, a 90-year-old former enslaved person.

W.W. Law: Activism and education began with grandmother of Savannah civil rights icon

More:Home of Savannah Civil Rights leader W.W. Law honored by Historic Savannah Foundation

Happy birthday, W.W. Law: Savannah civil rights icon would have turned 100 on New Year's Day

Barnard was an iconic figure in Savannah’s African American community and one of the earliest important influences on Law outside of the young child's immediate family. “Little West” Law was born on January 1, 1923, in a West Gwinnett Street house, just two blocks from the home where Barnard had lived for more than 40 years. Barnard and Little West’s grandmother, Lillie Belle Wallace, became neighbors in 1910, but their families had known each other far longer. They were fellow members of First Bryan Baptist Church. The church’s records show Barnard and Lillie Belle Wallace’s mother, Sarah Johnson, both contributed to the church’s building fund in 1873. Both had been born into slavery.

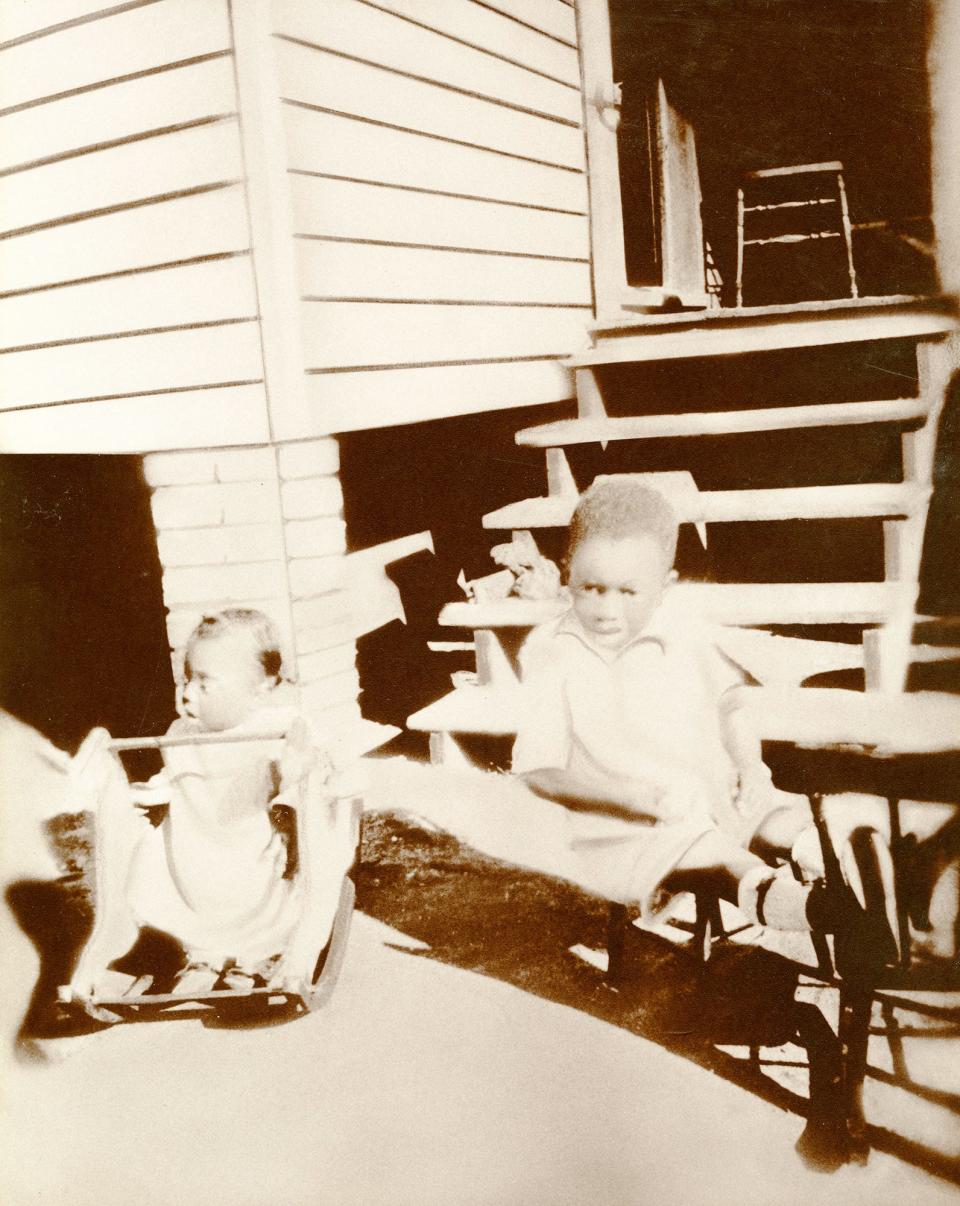

Shortly after Little West turned three years old in 1926, his family –– grandmother Lillie Belle, father Westley “Big West Law, mother Geneva and sister Dorothy –– moved to 33rd Street. Their new house was tucked in the middle of a block-long row of identical rentals in the busy Cuyler-Brownsville neighborhood. There were four rooms and a small kitchen for the three adults and two children in the Wallace/Law family.

Another baby was on the way. To make ends meet, they rented one of the rooms to Abraham Barnard.

Sharing lessons on the steps of 33rd Street

There is no known documentation of his exact birthdate, but U.S. Census records suggest Barnard was about 92-years-old when he moved into the house on 33rd Street. He captured Little West’s attention and cultivated the youngster’s imagination with his descriptions of plantation life on the nearby coastal islands, the coming of the Civil War and his later adventures encountering exotic sailors from faraway places while loading and unloading ships on the busy Savannah River.

Little West Law's world was safe and stable compared to the chaotic world of plantation slavery and civil war that Barnard described to him.

The depth of suffering Barnard’s family endured is documented in the records of the Savannah Branch of the Freedmen's Savings Bank. Authorities at the Reconstruction Era bank routinely quizzed formerly enslaved account holders about their lives before emancipation and recorded the answers alongside routine entries of deposits and withdrawals.

Barnard's bank record shows that his mother, Charlotte, died an enslaved woman around 1840, when Abraham was five- or six-years-old. His brothers, Richard and Alex, were sold away to New Orleans. Two sisters, Hagar and Sarah Ann, were both dead by 1870. His father, James, migrated to Liberia, where he died, never to see his surviving children again. What James Barnard had to do to get to Africa and how the news of his death traveled back to Georgia are unknown. It is the legacy of the instability of enslavement that none of the dates are concrete, none of the places certain, none of the circumstances were recorded in real time.

Barnard told Little West he was a Civil War veteran, a drummer boy in a Confederate militia unit. If Barnard ever identified his unit, or who was responsible for his attachment, Law didn't recall. No details of Barnard's involvement in the war survived him. It was not unusual for wealthy Confederate slave owners to bring their enslaved people with them when they went off to war, and it's possible that is what happened in Barnard's case.

Column: Savannah sets the standard for addressing ugly history of slavery, Civil War

Barnard owned a trunk that he kept under the cramped house on 33rd Street, where there were no closets and nails served as coat hangers. W.W. Law said Barnard would take the trunk out and display its contents to dramatize his stories about the Civil War. Inside was a trove of military and fraternal order regalia that fueled Little West's imagination. Among the clothes Barnard kept in the trunk were remnants of what he told the youngster was his Civil War uniform.

"I'd put on the uniform and march around the yard," Law said. Imagining what Barnard's Civil War experience had been, he said, "was one of the things that whet my appetite for the history of our people."

Barnard's trunk also contained sashes, ribbons, medals and other emblems of his membership in the Prince Hall Masons, the oldest and largest predominantly African American fraternity in the United States. He would sort through the artifacts and explain to Little West what they were and what they symbolized, withholding the secrets he had pledged to keep while enticing the child with their mysteries. "From my earliest years, I heard history," Law said. "The old folk talked about black leaders. Most were preachers, mainly Baptist. A few were businessmen and fraternal leaders."

Barnard, he said, was one of those fraternal leaders, "an officer of the lodge." The fraternal lodges were among the most important institutions that shaped Law's traditionalist ideology. Their members frequently were at the center of the oral histories he recited to diverse audiences, emphasizing the accomplishments of Savannah's African American community. The stories Law told functioned as counterpoints to the dominant narratives spun out for generations by white historians and journalists, which largely ignored black history.

A full life

Barnard’s personal stories were among Law’s first encounters with narrative style and racial pride.

Although no clear records of Abraham Barnard's enslavement have been discovered, records of his account at the Savannah Branch of the Freedman's Bank show he was living on Skidaway Island in 1870. U.S. Census enslaved people schedules from 1850 and 1860 include slave owners named Barnard. Other records indicate a prominent family of slaveholders named Barnard owned plantations on Skidaway and adjacent Ossabaw going back to the early 19th century, maintaining a few parcels and retaining some of the farmhands in the early years after Emancipation.

Freedmen sometimes took the names of the families that had enslaved them. Barnard could have been attached to a slave holder who fought in the Civil War, but there are no official records of such arrangements; and no letters or other private accounts of what he did and where he might have traveled have surfaced beyond W.W. Law's recollections.

Real estate records show Barnard regularly paid taxes on land and livestock he began to accumulate soon after being freed and into the 1920s. He is variously listed as a farmer and a longshoreman in city directories in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. He appears to have alternated between farming land on and near Skidaway Island, and working as a longshoreman on the Savannah River.

Law worked to make rights denied to Barnard a reality

In his later years, Barnard still owned and maintained a small plot of land adjacent to the segregated city cemeteries near his home on Gwinnett Street. The old man continued to raise vegetables there after he moved in with the Wallace/Law family. He named Lillie Belle Wallace executor of his will and she took care of him in his final years.

Barnard first registered to vote during Reconstruction, when the federal government forced Georgia officials to allow Freedmen to vote. He continued to pay poll taxes and cast ballots in general elections into the early 20th Century, when draconian literacy tests imposed by Georgia officials made it impossible for the former enslaved person and others like him to vote anymore.

From the Archives: Savannah’s W.W. Law

A bond application Barnard signed with business partners who intended to open a tavern in 1889 reveals why: For all his financial and civic accomplishments, Abraham Barnard never learned to read or write. He signed the application for a license to open a tavern with an "X."

W.W. Law spent his life fighting the legalized discrimination that limited the civil rights that Abraham Barnard and thousands of others were denied with the advent of the Jim Crow era.

More than 70 years after Abraham Barnard's death, Law described him simply, in the reverent tone he reserved for few people beyond his mother and grandmother. "He was an upstanding man," Law recalled. He said Grandmother Lillie Belle instructed the children "to be respectful and stay in your place" around the old man.

Abraham Barnard died when Little West was barely four years old, but the memory of the stories he told never faded, nor did the significance of the life he lived in the face of persistent adversity.

This article originally appeared on Savannah Morning News: Formerly enslaved Georgia man inspired Civil Rights activist WW Law