An urban Mexican American finds a sense of belonging in nature

The desert plants and animals that inhabit Hueco Tanks State Park and Historic Site have taught Nicole Roque important lessons in adaptation.

Mesquite trees can sprout roots more than 100 feet deep in search of water. Texas horned lizards change colors to blend into their environment. Desert crustaceans lay eggs that can stay dormant for decades before hatching.

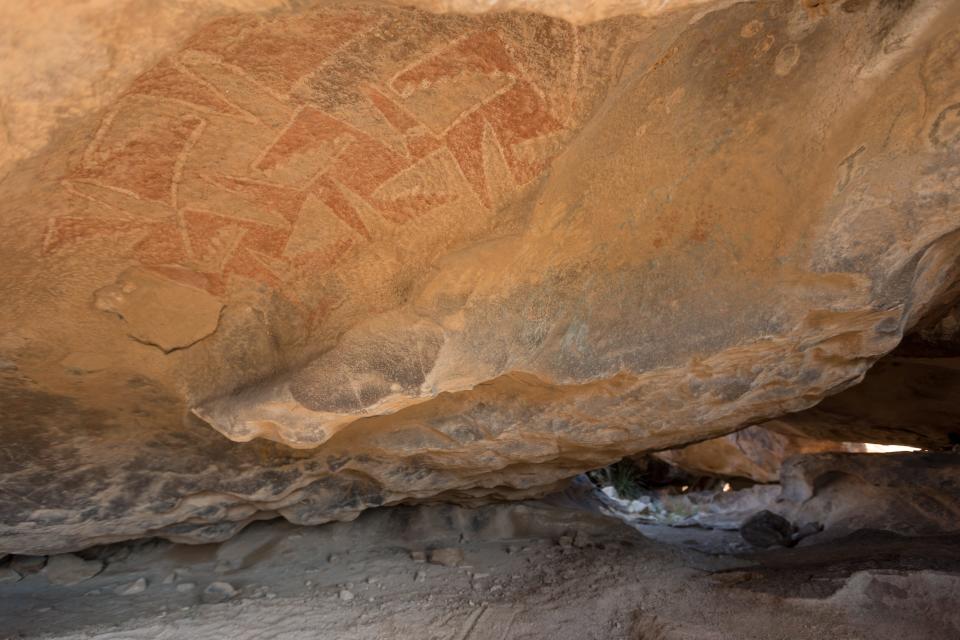

Roque, 32, is an interpretive guide at Hueco Tanks, a world-renowned destination for rock climbing and prehistoric pictographs 36 miles outside El Paso. Her journey to the job required a series of adaptations that now inform how she welcomes guests to the park — particularly those who are the least likely to visit.

“I really make an effort to help people feel more comfortable in coming to experience a place like this,” she said.

The rock formations at Hueco Tanks resemble giant knuckles on a clenched fist. Nestled within the park’s hardened surfaces is a fragile ecosystem of “living fossils” — tiny aquatic animals that date back to the era when dinosaurs roamed the Earth. They live in shallow water-filled depressions, the namesake huecos, in the rocks. Hueco Tanks limits its visitation to 70 people at a time to protect this ecosystem. Rock climbers, who tend to come from more affluent backgrounds and know how to use the park’s permitting system, often fill the park’s capacity in the cooler months of November through March.

“We have a line out at the gate to get into the park,” Roque said. “A lot of times, that prevents your average family from visiting. But we make every effort to educate people on how to do it. We keep talking to them, keep them excited. We show them pictures, give them brochures and … offer guided tours and that don’t count against the 70-person capacity.”

A city girl discovers her love of nature

Roque can relate to the average El Paso family.

She was raised by her single father, who braided her hair with help from a how-to book and dressed her in sandals and socks. He worked in an auto shop down the street from the East El Paso apartments where they lived. Roque spent weekends at the shop playing with tools and gadgets whose names she didn’t know. To this day, the smell of oil and rubber brings her comfort.

Her love of the natural world came from hours of watching the Animal Planet channel on TV. But finding nature in the city proved to be a challenge. The drainage ditch behind her apartment building became her playground. She and her friends would sometimes sneak into a neighboring golf course and watch geese waddle in an artificial pond.

“That’s where we found trees and grass, and that’s where we saw lizards and heard frogs,” she said. “To us, it was magical.”

Turning that awe into a career put Roque in unfamiliar territory. When she enrolled in New Mexico State University’s wildlife science program, she found most of her classmates were white and had grown up on ranches. Going to the sporting goods store to buy camping gear for her first field trip in Arizona’s Pinaleño Mountains, Roque felt overwhelmed.

“I was like, ‘I do not know what I’m doing and everyone is going to know I’m a fraud,’” she said. “But I definitely felt the support of my professors.”

One professor, in particular, recognized that Roque — an urban working-class Mexican American woman — was an underrepresented minority in the natural sciences field. The professor encouraged her to stick with the program.

Roque graduated in 2016 with a degree in wildlife science and conservation ecology. She started volunteering at the Franklin Mountains State Park and transitioned to a paid position via AmeriCorps. When a job opened up at Hueco Tanks in 2019, she applied and was hired.

“I empathize with people who are intimidated by the outdoors,” she said. “A lot of times there’s this image of what outdoors people look like, you know, the dudes with the gear and the hats and the glasses. That’s not what it needs to be. I hope that people see me and think, ‘Oh, she’s just a girl from El Paso. I can do that too.’”

Roque likes to emphasis that enjoying nature doesn’t require fancy gear, remote destinations or extreme sports.

“My love of the outdoors is sitting in a cave. It’s stopping and looking at flowers, listening to the birds, feeling the wind. That doesn’t require any sort of special knowledge or skills,” she said.

Racial inequalities limit access to the outdoors

A history of racial oppression in the U.S. has disconnected many minorities and people of color from nature. Minorities are more likely to live in cities and low-income neighborhoods that lack public green spaces. Minorities are also more likely to work in jobs that don’t allow them enough free time or disposable income for outdoor recreation.

Roque has visited with school children in El Paso who don’t know the name of the mountain range, the Franklins, that cuts through the center of their hometown.

“People don’t realize ... there are trails out there. You can climb there, you can hike there,” she said.

Another barrier she confronts is fear, which may be passed down subconsciously from a legacy of racial violence and discrimination. A century ago, Blacks and people of Mexican descent in the South and Southwest were lynched in the outdoors. During segregation, they were denied full access to public lands, including national forests and parks. This century, thousands of immigrants from Mexico and Central America have died traversing the American desert.

Examples of racial tension and violence in the outdoors continue. In 2020, a white woman made national headlines when she called the cops with a false accusation against a Black man who was birdwatching in New York’s Central Park. This year, three white men were sentenced to life in prison for killing Ahmaud Arbery, a Black man who was jogging in a suburban Georgia neighborhood.

More:For many Black Americans, the outdoors feel off limits. Black birders want to change that.

Roque said her relatives worry that her job means she’s sometimes outside by herself.

Fear manifests itself in a unique way in a southern border city such as El Paso. When doing community outreach, Roque is keenly aware that some locals might confuse her park ranger attire with a Border Patrol uniform.

“I get asked a lot, ‘Is (Hueco Tanks) past the Border Patrol checkpoint?’” she said. She tells them it is not. “I make an effort to be a welcoming presence for people and hopefully quiet some of those apprehensions.”

Finding a welcoming presence in nature

Roque found a welcoming presence while crawling between the stone crevices at Hueco Tanks: evidence of her ancestors embedded within the rocks. She identifies as Chicana, an American of Mexican descent who takes pride in her indigenous heritage.

Indigenous groups, including the Kiowa, Mescalero Apache and Tigua, consider Hueco Tanks a sacred place. An ancient people known as the Jornada Mogollon settled in Hueco Tanks around 1150 CE and grew squash, corn and beans. In Mexican culture, that trio of crops is known as milpa. Scattered throughout the park are deep holes carved into smooth stone.

“Archeologists call them bedrock mortars. We’ve always called them molcajetes,” Roque said.

These remnants revealed to Roque that she was not a stranger in these lands.

“It’s helped me feel this sense of belonging that I didn’t know I needed so deeply,” she said. “We don’t often see ourselves as Chicanos or as Mexicans, especially we who live in the city, as being connected to the environment, but we’ve been here and always have been.”

Mónica Ortiz Uribe can be reached at monica.ortiz@elpasotimes.com

This article originally appeared on El Paso Times: A Hueco Tanks park ranger helps more Latinos access the outdoors