Urban renewal planners didn't care about destroying Black structures | Opinion

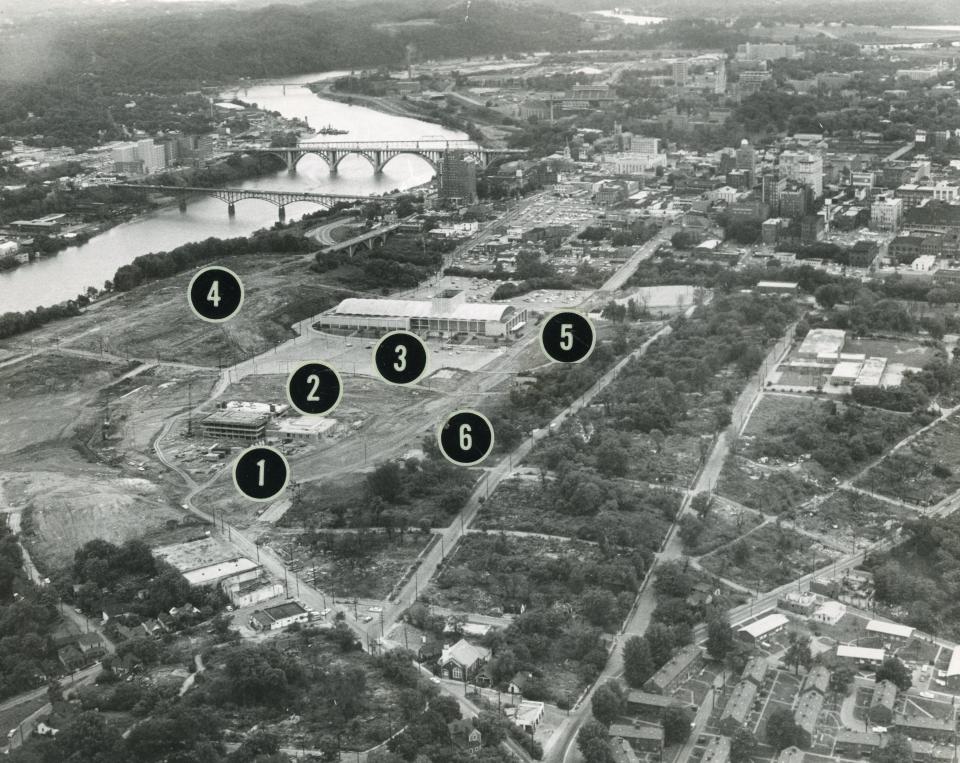

During the 16-year period of urban renewal projects between 1958 and 1974, historic Black structures were not considered for preservation. The mansion on Butler Street of Dr. James Henry Presnell, who had served as the "Bronze Mayor" of Knoxville, was destroyed like many of the substandard houses in the area. The list of iconic businesses that should have been saved is long.

One can read of and visit Black churches in Philadelphia, Baltimore, Charleston and other places, but the most historic and storied ones in Knoxville were destroyed. Mount Zion Baptist, which was established in 1860; Mount Olive Baptist, an 1869 church; and Shiloh Presbyterian Church, which was organized in 1865, were among those taken. There was no regard for what those places of worship meant to the community.

A long article in the Knoxville Journal of June 22, 1886, describes one of the local churches and its importance to the Black community: "The colored race of the south is just now beginning to rally from the effects of degeneracy imposed upon it by a long servitude and the late Civil War. To keep abreast of the times and progress in keeping with the civilization demanded, the colored people of Knoxville must have churches and school houses.

"The colored Methodist people, who have been worshipping in the old church in Marble Alley, decided last fall to erect a new church. The building is a handsome structure. The finish is first class in every respect and is nearly finished inside. This is one of the finest colored churches in the south and is the third largest in the country belonging to the colored people."

Hear more Tennessee voices: Get the weekly opinion newsletter for insightful and thought-provoking columns.

Yet that church, Logan Temple A.M.E. Zion, meant nothing to those who destroyed the Black business community along with 13 other Black churches. A lot of valuable land was in the offing, and those who made the rules did not care about Black pride of home ownership, business achievement or any other entity that stood in their way to affect a huge land grab with mostly federal dollars.

Your state. Your stories. Support more reporting like this.

A subscription gives you unlimited access to stories across Tennessee that make a difference in your life and the lives of those around you. Click here to become a subscriber.

Those rule makers were keenly aware of the irreparable harm they were causing but gingerly tiptoed around the one Black business that could disrupt the city's social norms. Closing the Gem Theatre would loose thousands of Black patrons on downtown movie houses, so it was was the only Black-patronized business left standing.

What those planners did not know was that the desegregation of downtown facilities would come in 1964 and render the Gem Theatre defunct as its patrons left to see first-run movies for the first time at the Tennessee and Riviera. The Gem became a popular nightclub before it was taken by the James White Parkway.

THE LATEST NEWS RIGHT AT YOUR FINGERTIPS

Get the latest local news, sports scores and more directly on your phone. Download the free Knox News mobile app.

Knoxville's Black community will never fully recover from the upheaval caused by urban renewal projects. The words from observers like me will never be adequate to describe the loss of a hundred years of history and economic growth.

Robert J. Booker is a freelance writer and former executive director of the Beck Cultural Exchange Center. He may be reached at 865-546-1576.

This article originally appeared on Knoxville News Sentinel: Urban renewal planners didn't care about destroying Black structures