Pence and Erdoğan agree on ceasefire plan but Kurds reject 'occupation'

The Turkish president, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, has agreed with the US vice-president, Mike Pence, to suspend Ankara’s operation on Kurdish-led forces in north-east Syria for the next five days in order to allow Kurdish troops to withdraw, potentially halting the latest bloodshed in Syria’s long war.

Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) fighters would pull back from Turkey’s proposed 20-mile (32km) deep “safe zone” on its border, Pence told reporters in Ankara on Thursday evening after hours of meetings with Turkish officials.

“It will be a pause for 120 hours while the US oversees the withdrawal of the YPG [a Kurdish unit within the SDF] … Once that is completed, Turkey has agreed to a permanent ceasefire,” Pence said, adding that preparations were already under way.

“Great news out of Turkey!” Donald Trump tweeted just before Pence spoke. “Millions of lives will be saved.”

The arrangement, however, appeared to be a significant US embrace of Turkey’s position in the weeklong conflict, and did not publicly define the safe zone’s borders.

General Mazloum Kobane of the SDF confirmed the ceasefire deal in comments to local television on Thursday night, but said it only applied to the area between the towns of Tal Abyad and Ras al-Ayn, both of which have seen heavy fighting.

Damascus and Moscow, who have since also moved troops into the contested border zone, also had no immediate comment. Erdoğan is due to meet his Russian counterpart, Vladimir Putin, in Sochi on Tuesday, where it is expected more concrete talks on the size of Turkey’s planned buffer zone will take place.

The initial plan was met with scepticism by many Syrian Kurds on Thursday night, as it gives the Turks what they had sought to achieve with the military operation in the first place: removal of Kurdish-led forces from the border.

When asked, Pence remained silent on whether the agreement amounted to a second abandonment of the US’s former Kurdish allies in the fight against the Islamic State.

A statement released after the meeting reiterated the US understanding of Turkey’s need for a safe zone which will be “primarily enforced by the Turkish Armed Forces” after the Kurdish withdrawal, implying that Ankara still intends to occupy the 270m (440km) stretch of land, which includes several important Kurdish towns and parts of a major highway.

It also made no mention of the presence of Syrian government and Russian troops, who were invited to the area by the SDF to help defend against the Turkish attack, and are not bound by the terms of the US-Turkish agreement.

“Our people did not want this war. We welcome the ceasefire, but we will defend ourselves in the event of any attack … Ceasefire is one thing and surrender is another thing, and we are ready to defend ourselves. We will not accept the occupation of northern Syria,” the Kurdish political leader Saleh Muslim told local television.

Who is in control in north-eastern Syria?

Until Turkey launched its offensive there on 9 October, the region was controlled by the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), which comprises militia groups representing a range of ethnicities, though its backbone is Kurdish.

Since the Turkish incursion, the SDF has lost much of its territory and appears to be losing its grip on key cities. On 13 October, Kurdish leaders agreed to allow Syrian regime forces to enter some cities to protect them from being captured by Turkey and its allies. The deal effectively hands over control of huge swathes of the region to Damascus.

That leaves north-eastern Syria divided between Syrian regime forces, Syrian opposition militia and their Turkish allies, and areas still held by the SDF – for now.

On 17 October Turkish president, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, agreed with US vice-president Mike Pence, to suspend Ankara’s operation for five days in order to allow Kurdish troops to withdraw.

How did the SDF come to control the region?

Before the SDF was formed in 2015, the Kurds had created their own militias who mobilised during the Syrian civil war to defend Kurdish cities and villages and carve out what they hoped would eventually at least become a semi-autonomous province.

In late 2014, the Kurds were struggling to fend off an Islamic State siege of Kobane, a major city under their control. With US support, including arms and airstrikes, the Kurds managed to beat back Isis and went on to win a string of victories against the radical militant group. Along the way the fighters absorbed non-Kurdish groups, changed their name to the SDF and grew to include 60,000 soldiers.

Why does Turkey oppose the Kurds?

For years, Turkey has watched the growing ties between the US and SDF with alarm. Significant numbers of the Kurds in the SDF were also members of the People’s Protection Units (YPG), an offshoot of the Kurdistan Workers’ party (PKK) that has fought an insurgency against the Turkish state for more than 35 years in which as many as 40,000 people have died. The PKK initially called for independence and now demands greater autonomy for Kurds inside Turkey.

Turkey claims the PKK has continued to wage war on the Turkish state, even as it has assisted in the fight against Isis. The PKK is listed as a terrorist group by Turkey, the US, the UK, Nato and others and this has proved awkward for the US and its allies, who have chosen to downplay the SDF’s links to the PKK, preferring to focus on their shared objective of defeating Isis.

What are Turkey’s objectives on its southern border?

Turkey aims firstly to push the SDF away from its border, creating a 20-mile (32km) buffer zone that would have been jointly patrolled by Turkish and US troops until Trump’s recent announcement that American soldiers would withdraw from the region.

Erdoğan has also said he would seek to relocate more than 1 million Syrian refugees in this “safe zone”, both removing them from his country (where their presence has started to create a backlash) and complicating the demographic mix in what he fears could become an autonomous Kurdish state on his border.

How would a Turkish incursion impact on Isis?

Nearly 11,000 Isis fighters, including almost 2,000 foreigners, and tens of thousands of their wives and children, are being held in detention camps and hastily fortified prisons across north-eastern Syria.

SDF leaders have warned they cannot guarantee the security of these prisoners if they are forced to redeploy their forces to the frontlines of a war against Turkey. They also fear Isis could use the chaos of war to mount attacks to free their fighters or reclaim territory.

On 11 October, it was reported that at least five detained Isis fighters had escaped a prison in the region. Two days later, 750 foreign women affiliated to Isis and their children managed to break out of a secure annex in the Ain Issa camp for displaced people, according to SDF officials.

It is unclear which detention sites the SDF still controls and the status of the prisoners inside.

“We’ve previously stated that Turkey’s proposal of entering a depth of 30km inside Syrian territories is rejected,” Aldar Xelil, another senior political figure, was quoted by local media as saying after news of the Ankara agreement broke.

The deal was “a great day for civilisation”, Trump told reporters before praising Erdoğan as “a hell of a leader”.

Trump seemed to endorse Turkey’s aim of ridding the Syrian side of the border of the Kurdish fighters who fought Isis on behalf of the US – but who Ankara regards as proxies for the Kurdistan Workers’ party (PKK) that has waged a 35-year insurgency against the Turkish state. “They had to have it cleaned out,” he told reporters.

But the deal was condemned by the Republican senator Mitt Romney, who said Trump’s decision to abandon Kurdish allies in Syria “will stand as a bloodstain in the annals of American history”.

In Ras al-Ayn, one of the two border towns under attack by Turkey, warplanes and drones were still flying overhead and ground fighting between the SDF and Syrian rebels allied to Turkey continued.

The US and Turkey have “mutually committed to peaceful resolution and future for the safe zone”, Pence said. In return, the US will not impose further sanctions on Turkey and remove those that were imposed last week once the permanent ceasefire takes hold.

The senior US delegation had travelled to Ankara with the stated task of pressuring Turkey to halt its offensive in north-east Syria or face sanctions, hours after Donald Trump said his country had no stake in defending Kurdish fighters who died by the thousands as the US’s partners against Isis.

On Wednesday Trump hailed his decision to withdraw US troops in Syria, paving the way for the Turkish offensive, as “strategically brilliant”, declaring that the Kurds he had abandoned were “much safer now” and were anyway “not angels”.

His remarks not only undercut the mission to Ankara but contradicted the official assessment of both the state and defence departments that the Turkish offensive was a disaster for regional stability and the fight against Isis.

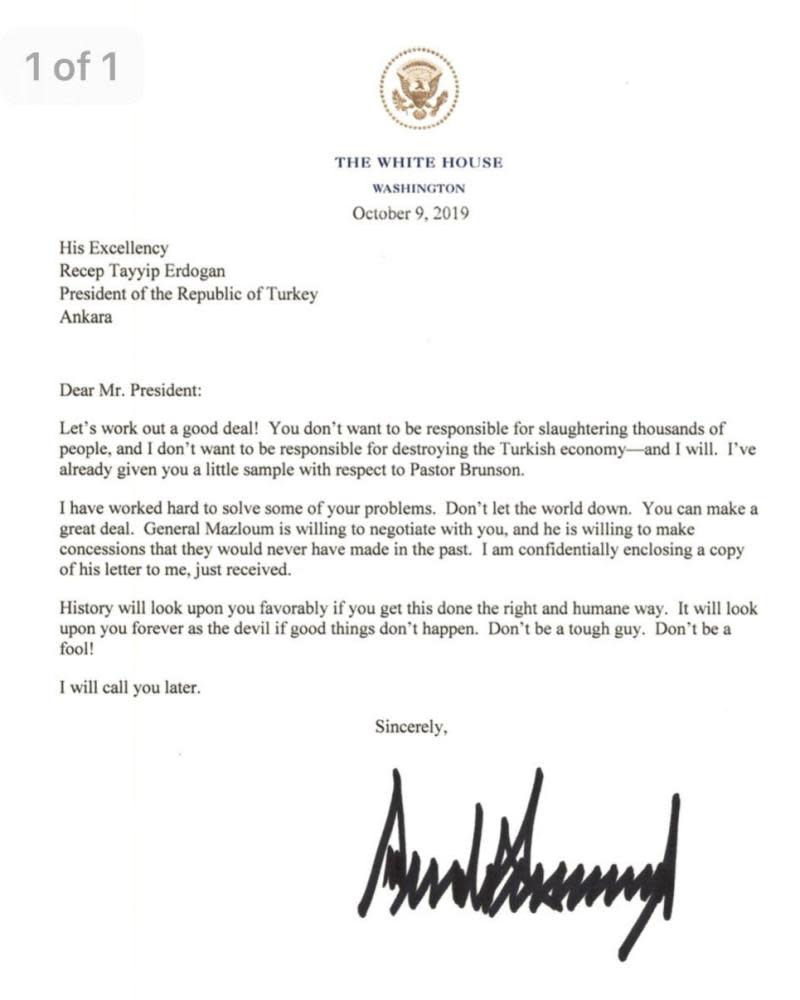

In two further extraordinary developments, a bizarre letter from Trump to Erdoğan emerged in which the US president warned his Turkish counterpart “don’t be a fool”, and a White House meeting with Democratic lawmakers descended into mutual accusations of “meltdowns”.

The letter was sent on 9 October – three days after a phone call in which Erdoğan informed Trump of his plans, and understood the US president had given a green light. Trump issued a statement announcing the offensive was about to happen and that US troops would be moved out of the way. He also invited Erdoğan to the White House.

Trump wrote: “History will look upon you favourably if you get this done the right and humane way. It will look upon you forever as the devil if good things don’t happen. Don’t be a tough guy. Don’t be a fool!”

On the day the letter was received, Erdoğan launched his offensive to create a buffer zone between Turkey and territory held by the SDF.

The Turkish president had insisted earlier on Wednesday he would “never declare a ceasefire”.

While Erdoğan has faced global condemnation for the operation, it is broadly popular at home, and any pathway to de-escalation probably needed to avoid embarrassing him domestically.

On Wednesday, two-thirds of House Republicans supported a resolution condemning Trump’s decision to withdraw troops.

Related: Democrats walked out of Syria meeting after Trump had 'meltdown', Pelosi says

The vote triggered what the House speaker, Nancy Pelosi, described as “a meltdown” by the president when she and other members of Congress visited him in the White House.

Pelosi and other top Democrats said they walked out of a contentious White House meeting after it devolved into a series of insults and it became clear the president had no plan to deal with a potential revival of Isis in the Middle East.