The US government once set off nuclear bombs in Mississippi. How bad were the explosions?

During the height of the Cold War, the United States government conducted two underground nuclear weapons tests in the Pine Belt region of Mississippi near Hattiesburg.

These tests, which explored the feasibility of underground weapons testing, set Mississippi as one of only five U.S. states to have experienced a nuclear weapons explosion.

By the 1960s, the Cuban Missile Crisis had nearly brought humanity to the brink of annihilation and the world was on edge. Meanwhile, previous above-ground nuclear weapons testing proved to have devastating environmental consequences.

In response, the Soviet Union and the U.S. signed the 1963 Partial Test Ban Treaty, prohibiting above-ground, underwater, and space-based nuclear weapons tests. However, the U.S. and Soviet Union were unable to come to an agreement on underground tests as both believed it was possible to cheat on such a treaty.

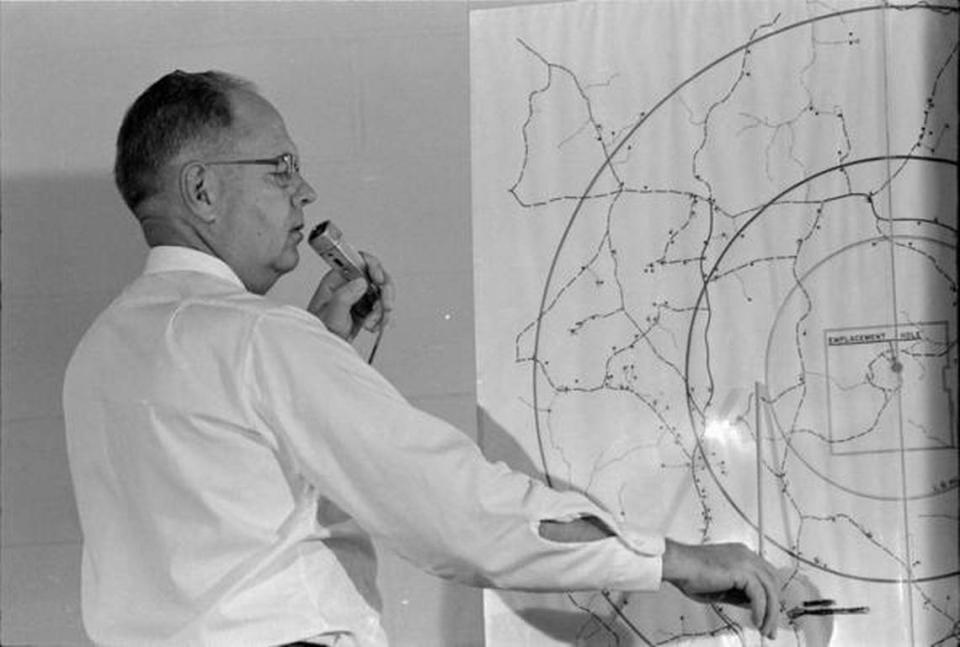

Prompted by this opportunity, the U.S. government launched Project Vela Uniform, a joint effort by the Department of Defense and the Atomic Energy Commission. The project aimed to study seismic activity resulting from underground nuclear blasts and improve the detection of such tests if conducted by the Soviet Union or China.

In a departure from previous tests done in remote locations like island chains or arid deserts, the area near Hattiesburg emerged as an unconventional option. While the state had a smaller population compared to others, it still possessed abundant natural resources and concerns were raised regarding the impact on local communities and the environment.

Underneath Lamar County, Mississippi, lay the Tatum Salt Dome, a unique geological formation with a 2,700-foot depth and a layer of thick salt beneath the sedimentary basin. This site was deemed ideal by the Department of Defense and the AEC, who green-lit Project Dribble to test and record seismic readings from two nuclear explosions within the dome.

Instead of the covert or highly classified nature of previous tests, Mississippi locals, media, and even the Soviet Union were warned of these tests and their purposes. Some Mississippi residents complained of the dangers inherent in such a test, but were ignored and told it was a matter of national security.

On October 22, 1964, local schools and businesses were closed and residents within a 2-mile radius of the blast were evacuated. Journalists, scientists, and even some locals gathered in designated observation points to witness the test. Project Salmon, code-name for a 5-kiloton bomb about a third the size of the one that destroyed Hiroshima, was detonated underground at 12:00PM.

The explosion was drastically worse than local residents were led to believe, with many reporting that the earth’s crust moved like ocean waves. In fact, later reports confirmed that the crust was lifted as high as four inches in some places. Residents as far away as Hattiesburg felt the explosion. Within a week, local wells and creeks had dried up and over 400 residents of the area had filed reports of damages to their chimneys, foundations and windows.

The explosion left a cavity nearly 110 feet wide beneath the crust. Seismic stations as far away as Finland recorded activity from the blast. The test proved successful for the U.S. government, demonstrating that underground detonations could be detected even in distant locations like the Soviet Union.

On December 3, 1966, another test, Project Sterling, was conducted in the salt dome cavity with a significantly smaller bomb. Local residents reported that they barely felt the resulting explosion. This test proved that a damp cavity underneath the earth could muffle the shock-waves of a small nuclear explosion.

With that knowledge, the U.S. came to the realization that detecting underground nuclear tests was possible, but so too was cheating on any underground test ban. These tests were the only known nuclear weapons detonations in the Eastern half of the U.S.

Project Dribble was followed by two additional non-nuclear explosions, referred to as Project Miracle Play, at the Tatum Salt Dome in 1969 and 1970. In the early 1970s, contaminated buildings, soil, and liquids from the area were disposed of.

Over the years, some locals have reported health issues and even attributed cancer deaths to the residual effects of the nuclear weapons tests. However, the government denies these claims, and no scientific correlation has been established between the tests and cancer rates in the area.

Today, no residents live above the area where these tests occurred, now known as the Salmon Site. A small granite plaque serves as a solemn reminder, warning future generations not to dig in the area.