The US isn’t ready for stronger hurricanes, experts say. How structures are built could help.

As southwestern Florida reels from Hurricane Ian’s devastation, residents can look to recovery efforts following other recent major storms for a roadmap back.

It could take years, experts say — and as hurricanes get stronger and buildings nationwide remain outdated, that may be the norm.

Hurricane recovery can last at least a decade and sometimes longer, said Tracy Kijewski-Correa, an engineering and global affairs professor at the University of Notre Dame who has worked on several major disasters, including 2017's Hurricane Harvey in Texas.

TROPICAL STORMS GETTING WETTER: Is climate change fueling massive hurricanes in the Atlantic? Here's what science says.

“We worked in communities after Sandy, they were still — and still are — trying to recover,” Kijewski-Correa said, referencing the "superstorm" that hit New Jersey's coastline in 2012.

A similar lengthy timeline could be in store for Ian survivors, said University of South Florida College of Public Health instructor Elizabeth Dunn.

“Having to rebuild all these homes, grocery stores, the infrastructure, it's going to be years for that recovery process to occur,” she said.

The cost of a hurricane

Taking into account individual payouts, federal disaster funds allocated to impacted states and agricultural losses, NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Information lists 2005’s Hurricane Katrina, which slammed coastal Louisiana and Mississippi as a Category 3 storm, as the costliest hurricane to strike the U.S. It totaled over $186 billion in damage.

As of Aug. 10, more than 73,000 Katrina survivors were getting assistance through FEMA's direct housing program, spokesperson Jaclyn Rothenberg said.

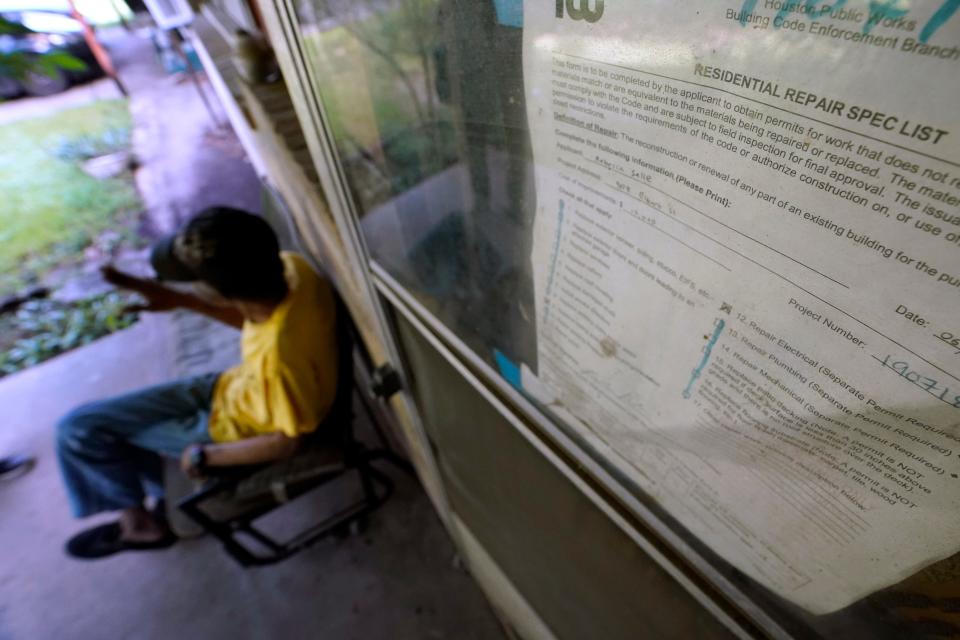

More recently, a 2022 University of Houston study found 82% of Houston's households have recovered from Hurricane Harvey's flood and wind damage in Texas, but over 18% of respondents — mostly in marginalized communities — reported ongoing recovery struggles five years later.

Hurricane Harvey is the second-costliest hurricane on record, hitting Texas for $148 billion in damage.

'NIGHTMARE' IN PUERTO RICO: Hurricane Fiona knocks out power, floods homes

5 YEARS LATER: Puerto Ricans are still struggling with Hurricane Maria's devastation. Then came Fiona.

Andrew Barley, disaster rebuild manager of Houston-based nonprofit West Street Recovery, called the weather events that have plagued the city post-Harvey, including a 2021 ice storm, a “perpetual chain of disaster.”

“The year after (Harvey), we had another storm that flooded a lot of the same areas,” Barley told USA TODAY, adding that in 2022, the organization continues Harvey-related repair work in marginalized parts of Houston.

Tropical cyclones over the past 41 years have each caused an average of $20.5 billion in damage, according to NOAA's Office for Coastal Management.

FEMA: Outdated building codes put lives at risk

A 2020 FEMA report showed 65% of U.S. counties, cities and towns have not adopted modern building codes.

“Building codes generally are not providing the level of protection a family needs to be able to return to an occupiable home after a hurricane,” Kijewski-Correa said.

FEMA's study found that updated hazard-resistant building codes could avoid at least $32 billion in losses from disasters including hurricanes, which accounted for the most losses of all disasters over a 20-year period.

Hazard-resistant upgrades include improved roof construction standards like roof tie-downs and coverings, mandated use of impact-resistant windows and window covers and strengthened walls, according to FEMA.

Communities not built according to modern standards are left “exceptionally vulnerable," Kijewski-Correa said.

"(Experts) routinely communicate the risks communities are facing and the measures they should take to protect themselves, but we don't see uptake,” she said. Engineers update model building codes about every four years, leaving it up to individual communities to adopt the latest recommendations, Kijewski-Correa said.

HURRICANE IAN AFTERMATH: This woman survived her 'biggest mistake' in Ian. Why experts say many others didn't.

HURRICANE SEASON CONTINUES: Forecasters warn Central America to watch new tropical system

A 2021 Insurance Institute for Business and Home Safety report ranked eight states along the hurricane-prone Gulf and Atlantic coasts — Texas, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, Delaware, New York, Maine and New Hampshire — with poor ratings on a zero-to-100 scale based on their adoption and enforcement of modern building codes.

Mississippi and Alabama scored the lowest at 29 and 30, respectively, and none of the eight lowest-ranked states have mandatory statewide building codes, the report found.

Florida — the hurricane capital of the U.S., according to the International Hurricane Research Center — and Virginia were ranked highest for having most updated building codes against loss prevention, the study showed.

'Reactive' versus 'proactive' investment

The U.S. will never get on the right track if remains a "reactive country," not proactively investing in measures to make hurricane-prone areas safer, said Kijewski-Correa.

“We let things get broken and insurance pays for it; we let communities be destroyed and then FEMA comes in and we rebuild it,” she said. “We rarely come and say, ‘we're going to come in and strengthen these things before the storm,’ proactive investment.”

Newer structures in much of Florida, especially in the south, were built to stronger codes after hurricanes like 1992’s Andrew and 2004’s Charley, according to the Insurance Institute for Business and Home Safety and the Florida Housing Finance Corporation.

The Insurance Institute's post-Charley study found Florida's building code improvements in 1996 reduced residential property damage claims by 60% and dropped the severity of damage to buildings by 42%.

However, parts of the Florida Panhandle decimated by Category 5 Hurricane Michael in October 2018 were under building code exemptions that left them vulnerable. Some buildings in the Mexico Beach area weren't designed to withstand winds from a Category 5 storm, a report from the Florida Department of Business and Professional Regulation found.

"Poor siting and elevation" also led to the extent of Michael damage in the area, according to the report.

Building codes in the area had been allowed exemptions because they had not been hit before by a major storm, Kijewski-Correa said, who added storms are taking paths they historically had not.

“In a changing climate, I don't know how long those historical precedents are going to hold,” she said.

When a region hasn’t fully recovered from previous storms and gets affected by additional natural disasters soon afterward — which researchers call compounding disasters — Kijewski-Correa said an area’s vulnerability drops with each impact.

“Now, we’re getting hit more often,” she said, and it’s not just by hurricanes. Flooding, heat waves, tornadoes and cold snaps all weaken a community’s resilience, according to Kijewski-Correa.

Better building codes? Or more consumer education?

In addition to adopting updated codes, Kijewski-Correa recommended a societal shift to performance-based building standards where homeowners can choose the level of their home’s safety.

“I could say to my builder, ‘I want a home that will be standing after a Category 4 hurricane,’ and they would design the home to that standard,” she said.

The Life Safety Code applied to buildings in the U.S. and globally is designed to get people out alive, and doesn’t mean the building won’t be significantly damaged in an event like a hurricane, which could "max out" building codes, Kijewski-Correa said. Performance-based designs would allow homeowners to build above code standards, she said.

Building codes aren’t retroactive and only apply to new construction, she noted. The lag in catching up to code standards is why the engineer said she doesn’t believe building codes are necessarily the answer.

“I actually think the answer is educating consumers about their risk and giving them products in the market that allow them to make choices to better protect their family, and that allow them to voluntarily upgrade their home or retrofit it,” Kijewski-Correa said.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Future after Hurricane Ian? Some buildings aren't ready for new storms