US says only 'weeks' remain to revive nuclear deal with Iran

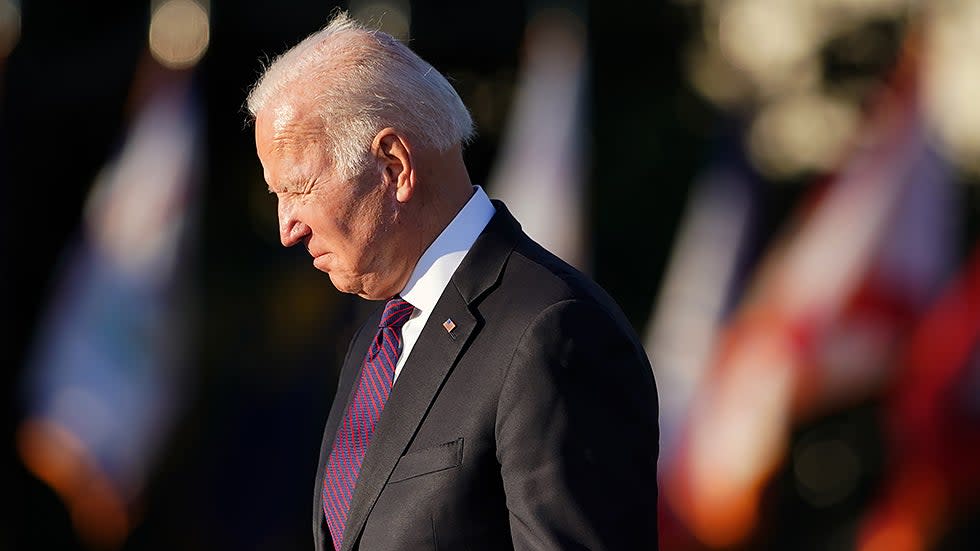

President Biden is reaching a make or break moment in his pursuit of reviving the 2015 nuclear deal with Iran.

One year into the Biden administration, officials say that only a few weeks remain to save the agreement before Iran advances its nuclear capabilities beyond reversal, raising fears it will build a weapon of mass destruction.

A senior State Department official told reporters on a call Monday that the U.S. and Iran only have "a handful of weeks left to get a deal."

"We are in the final stretch," the official said. "This can't go on forever because of Iran's nuclear advances."

The White House has said it is committed to diplomacy to revive the agreement, formally called the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), but is "preparing alternative options," in particular with Israel, should the talks collapse.

But experts and analysts are encouraged that an initial agreement is forming among the parties as the eighth round of talks in Vienna concluded over the weekend and officials are back in their respective capitals to discuss concrete decisions on moving forward.

"Now is the time for political decisions," the official said. "Now is the time for Iran to decide whether it's prepared to make those decisions necessary for a mutual return to compliance with the JCPOA."

Iranian officials have raised the possibility of engaging directly with the U.S. after nearly a year of European, Russian and Chinese diplomats shuttling between the two sides as negotiating intermediaries. The senior official suggested Monday that direct talks could accelerate an agreement, though stressed that a deal is not guaranteed.

Critics are likely to sharpen their opposition as the U.S. and Iran move closer to reviving the JCPOA. They argue the pathway to an agreement - relieving sanctions and allowing Iran to access to international markets - will only serve to enrich their ballistic missile program and support for terrorist proxies throughout the region.

Two top officials on the U.S. negotiating team have stepped down - deputy special envoy for Iran Richard Nephew and Ariane Tabatabai, a senior adviser in the State Department arms control bureau - reportedly over concerns that special envoy for Iran Rob Malley's team is being too dovish on sanctions relief with Iran.

The State Department has said that Nephew is moving to another job in the agency and the official on Monday said that while it's a "regret" that he is moving on, it's not unusual and that the policy of the administration remains tightly focused on returning to the JCPOA.

"It's not a matter of personal differences. It's a matter of policy that the administration has settled on and that everyone serving the administration is pursuing," the official said.

The Biden administration argues that the JCPOA is the best chance to immediately impose strict limits on Iran's nuclear activity and open it up to intrusive international monitoring.

"We still believe that if we can get back in the weeks ahead - not months ahead, weeks ahead - to the JCPOA, the nuclear agreement, that would be the best thing for our security and the security of our allies and partners in the region," Secretary of State Antony Blinken told NPR earlier this month, adding, "The runway is very short."

Amid the time crunch, administration officials and experts appear cautiously optimistic about the prospect of a deal.

"After months of uncertainty, of delay - a path over returning to the deal is coming into view," said Suzanne DiMaggio, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace where she is an expert on diplomacy with Iran.

"Wide gaps on key issues, particularly assurances on sanctions relief and sequencing remain, but there appears now to be a focused effort to bridge those gaps through creative diplomacy," she said.

Dennis Ross, a former special assistant to President Obama and expert in Middle East policy, said that the Iranians have signaled in public comments that they are more interested in coming to an agreement than they were in the previous year.

"Being ready to do a deal is not the same as being anxious to do it," Ross added. "Do they feel sufficient pressure to get sanctions lifted enough to do a deal?"

Participants to the Vienna talks are working to finalize an "outcome document," Russia's lead negotiator, Mikhail Ulyanov, tweeted last week - a sign that concrete agreements on some issues are being put in writing.

Iran's foreign minister has also indicated Tehran is open to engaging in direct talks with the U.S. in Vienna.

The negotiators in Vienna have so far managed to isolate themselves from broader geopolitical tensions playing out - between the U.S., Europe and Russia over threats to Ukraine; poor relations between the U.S. and China over the battle for global supremacy; and closer ties between Moscow and China in opposition to the U.S. and its western allies.

Still, there is a threat that ties between Iran, China and Russia may grow stronger as tensions with the U.S. and Europe further pull the world apart.

Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi has made economic recovery a pillar of his administration, and looked to strengthen Tehran's relations with China and Russia to realize that. Raisi met with Russian President Vladimir Putin on Jan. 19 and China is importing Iranian oil despite sanctions from the U.S.

DiMaggio says that these closer relations are still reliant on sanctions relief, which can strengthen the hand of the U.S. in the Vienna talks, but that the diplomatic balance is delicate.

"Any shift in Iran's currently depressed commercial relations with these countries, hinges on the lifting of U.S. extraterritorial sanctions, so this is a very key incentive for the Iranians to revive the deal," she said.

If the talks fail, one of the contingency options is strengthening sanctions, and that include targeting more forcefully China's imports of Iranian oil. But DiMaggio says that these options don't address the most troubling issue, Iran's buildup of its nuclear capabilities.

"For the Biden team, versions of potential plan B are being contemplated, and they are naturally more coercive in scope and they include a range of more economic pressure, but the problem is there's no evidence to suggest that such approaches would produce a different result," she said.

"In fact, Iran's nuclear program is more advanced today than it's ever been, even in the face of 'maximum pressure,' " she continued, referring to the campaign name used by the Trump administration to impose an estimated 1,500 sanctions on Iran to force it to negotiate a better deal that never materialized.

Any alternative plan for the Biden administration is likely to be tightly coordinated with the Europeans, said Naysan Rafati, senior analyst on Iran with the International Crisis Group.

"There's virtually no daylight between the E3 and U.S. position, and if we get to a point where we come to a judgment where the existing framework doesn't work, I think the odds are that whatever the Europeans do, and whatever the Americans are going to do, are going to be fairly, tightly coordinated," Rafati said.

As the Vienna talks progress, Republican critics of a potential nuclear deal could use any breakthrough of an agreement as fodder to criticize Biden and Democrats leading up to the midterm elections.

Republicans and even some Democrats were opposed to the 2015 deal brokered by the Obama administration, which they argued was insufficient in curtailing Tehran's nuclear ambitions. Trump withdrew the U.S. from the pact in 2018 in a break with European allies.

The senior State Department official said Monday that Iran is "weeks, not months" away before it has enough fissile material to make a nuclear bomb.

"It doesn't mean they've given up their nuclear weapon option, it means they are closer to where they would have been and they're agreeing to effectively put it on hold until 2030," Ross said of a renewed agreement. "If you don't stop their current advance, you are left with nothing short of use of force."