US Supreme Court to hear Brackeen v. Haaland, a case challenging Indian Child Welfare Act

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The U.S. Supreme Court recently announced it will grant cert to, or hear, Brackeen v. Haaland, a case that challenges the Indian Child Welfare Act.

The Indian Child Welfare Act, also known as ICWA, establishes federal standards for the placement of Indigenous children in foster or adoptive homes. Sometimes referred to as a “gold standard” for child protective services, ICWA aims to protect Indigenous children by giving the child’s tribe and family the opportunity to be involved in decisions they previously may have been excluded from, including determining services and placement for a child.

In a joint statement released on Monday, Chuck Hoskin Jr., principal chief of the Cherokee Nation, Charles Martin, chairman of the Morongo Band of Mission Indians, Tehassi Hill, chairman of the Oneida Nation, and Guy Capoeman, president of the Quinault Indian Nation, said they "look forward to once again seeing ICWA fully upheld, as courts have repeatedly done for over four decades."

"As leaders of our respective tribes, we know the importance of keeping our children connected with their families, communities and heritage. ... We will never accept a return to a time when our children were forcibly removed from our communities and look forward to fighting for ICWA before the court," they said in a statement.

Subscription sale: Get 6 months of unlimited access for just $1. Subscribe today!

Opponents of ICWA, generally argue that the law is discriminatory, as it imposes "race-based" restrictions on foster care and adoption, which may not be in the child's best interest.

But some legal experts say that idea is misguided.

"ICWA is very clearly based on citizenship rather than race," said Buddy Rutzke, an assistant public defender in Bozeman, told the Tribune in January 2020. "Membership in a Native American nation means that a child is both a citizen of the United States as well as the nation in question. Whether ICWA applies to a case does not depend on a child’s race, it depends on whether he or she has, or is eligible to have, citizenship status with a Native American nation."

What is Brackeen v. Haaland?

Plaintiffs Chad and Jennifer Brackeen, a couple from Texas, and state attorneys general in Texas, Louisiana and Indiana, sued the Department of the Interior and former Secretary Ryan Zinke, challenging ICWA in 2017.

At the time, the couple sought to adopt a child who is eligible for membership in the Navajo and Cherokee nations. Their request was initially denied after Navajo Nation found a potential Native American home in New Mexico, according to The Associated Press. But, in 2018, the couple was able to adopt the child after the placement fell through.

Plaintiffs challenge the constitutionality of ICWA, arguing that it violates the equal protection clause, which guarantees equal protection under the law, and the anti-commandeering doctrine, stating that the federal government cannot require states to adopt or enforce federal law.

'It's about time!': Tribal members in Montana celebrate Deb Haaland's historic confirmation

Four tribes — the Cherokee Nation, Oneida Nation, Quinalt Indian Nation and Morengo Band of Mission Indians —intervened as defendants in the case. And in December 2019, 486 federally recognized tribes filed an amicus brief to the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals defending the constitutionality of ICWA. Montana tribes defending ICWA's constitutionality include: the Assiniboine and Sioux Tribes, Blackfeet Nation, Chippewa Cree Tribe, Crow Nation, Fort Belknap Indian Community, Northern Cheyenne Tribe and Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes.

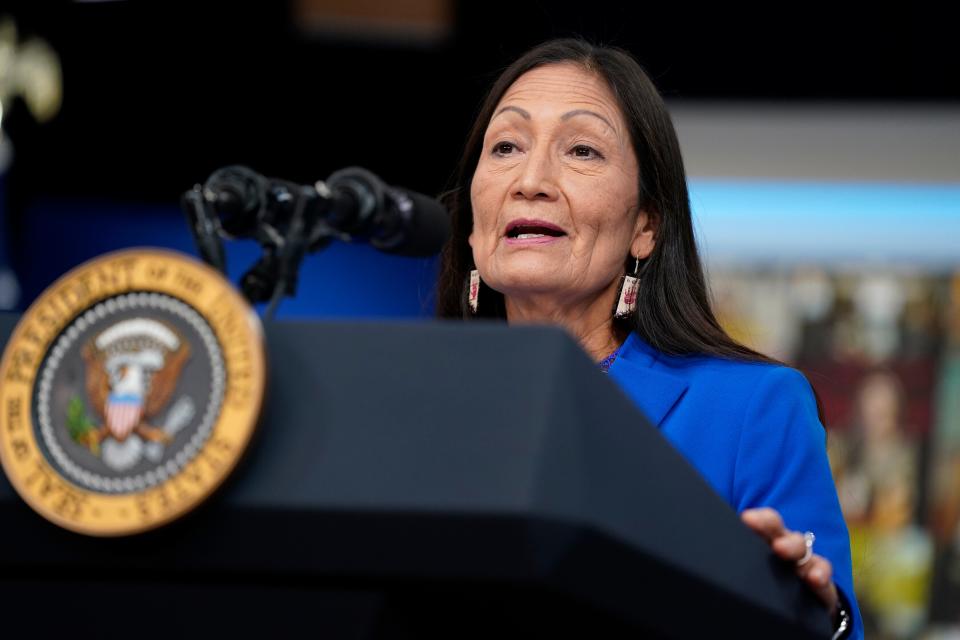

Plaintiffs sued the U.S. Department of the Interior and previous Secretary Ryan Zinke (who was also a Montana congressman). The case was later transferred to David Bernhardt, who succeeded Zinke as Interior Secretary in April 2019, now to Deb Haaland, who was appointed Interior Secretary last March. A member of the Laguna Pueblo Tribe, Haaland became the first Native American to serve as a cabinet secretary.

In August 2019, the Fifth Circut Court of Appeals upheld ICWA's constitutionality in the case, but in October 2019, plaintiffs requested an en banc rehearing before the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals. In April 2021, the court upheld some aspects of ICWA, recognizing that it is generally within Congress' authority.

How does the Indian Child Welfare Act work?

For decades, state child welfare and private adoption agencies separated Indigenous children from their families and communities.

In response to the disproportionately high number of Indigenous children separated from their families, ICWA was enacted in 1978 to establish federal standards for the placement of Indigenous children in foster or adoptive homes, giving preference to Native American families.

Local Connection: A deeper look into the Indian Child Welfare Act and its possible role in Antonio Renova's death

According to the National Indian Child Welfare Association, or NICWA, the Act requires that states place Native American children in foster care first with their extended family. If that is not possible, they should be placed with a foster family licensed or approved by the child’s tribe. If that’s not possible, the child should be placed with a non-Indigenous agency.

When handling ICWA cases, caseworkers are supposed to provide “active efforts” (or thorough and timely efforts intended to maintain or reunite a Native American child with their family) to identify a placement that aligns with ICWA provisions and notify the child’s tribe and the child’s parents and extended family in the case.

Why does it matter?

Forty-four years after ICWA was enacted, Indigenous children are still overrepresented in foster care.

According to NICWA, Indigenous children are four times more likely to be removed by state child welfare systems than non-Native children, even when their families have similar presenting problems. Native children are also overrepresented in the foster care system at a rate 2.1 times greater than their proportion of the population, according to the same report.

In most cases, Child Protective Services aims to connect children with their family members. Studies show that children cared for by relatives or close family friends experience greater stability, report more positive perceptions of their placements and demonstrate fewer behavioral problems compared to children in foster care.

For Indigenous children, living with family members can be especially important because much of Indigenous culture and tradition is based in a family context.

This article originally appeared on Great Falls Tribune: US Supreme Court will hear challenge to Indian Child Welfare Act