USA TODAY's Harrison Hill tells migrant stories through portraits

My assignment for USA TODAY’s ambitious project on the migrant crisis was to cover immigration court in Los Angeles. I knew this would be a tough assignment to visualize as photography and videography are not allowed inside of a federal courthouse.

For the project, the USA TODAY Network wanted to show, not tell, what was happening in real-time. Reporting spanned one week in June and took place across the U.S., Mexico, El Salvador and Guatemala. I was one of almost 30 journalists who reported during that week. My assignment: Tell our readers what it's like to face a judge and ask for asylum in the U.S.

After spending a day getting background from legal representatives at the courthouse in L.A., I learned that the number of asylum cases had grown exponentially, and that more than likely I would not see the same person twice during my week of reporting. I knew every person coming through immigration court had a unique story to tell, I just needed to find the best way to tell it visually.

After a couple of days on the assignment, fellow USA TODAY reporter Jared Weber and I found ourselves at El Rescate, a non-profit that offers legal services for individuals seeking asylum in the United States. That day they were offering walk-in consultations for families looking for asylum in the United States. With the opportunity of being around that many migrant families looking for legal advice in a single day, I asked if I could set up a photo studio in their building to interview and capture portraits of individuals after their consultations.

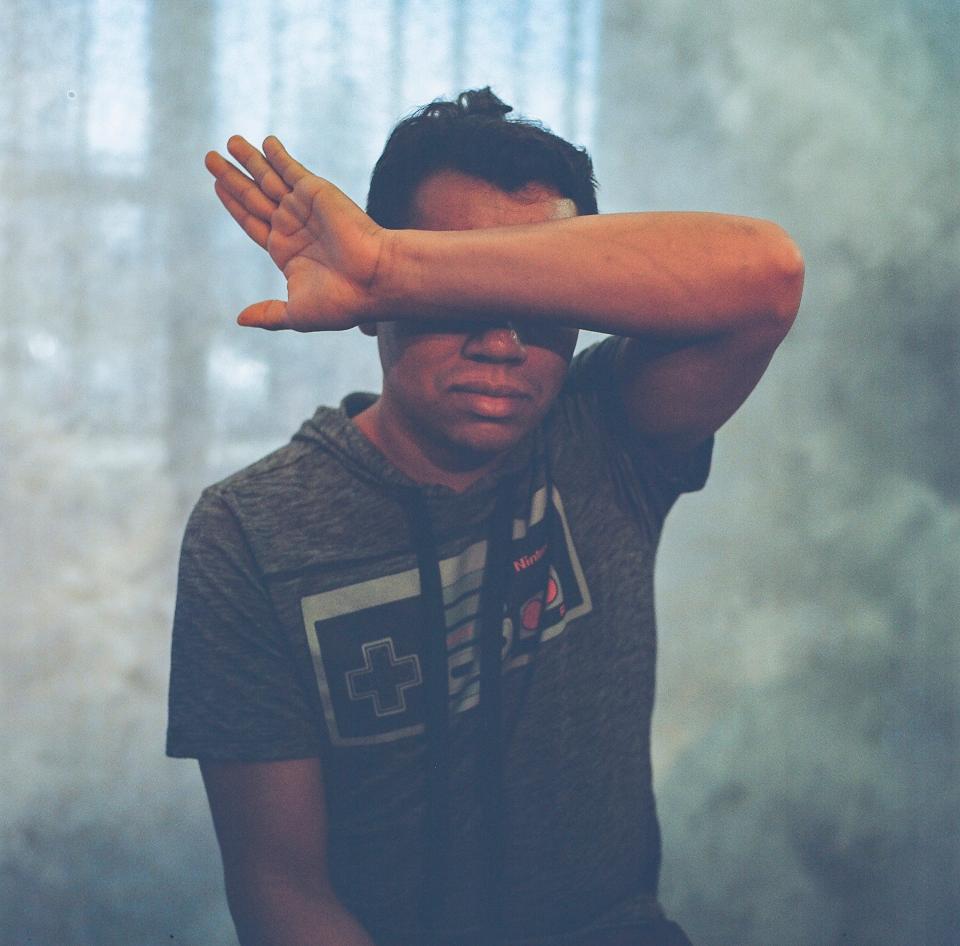

I received approval for the studio, which consisted of a Fiilex dual power LED light and a grey translucent backdrop that I placed in front of a window in the back room of El Rescate. After their legal consultations, every family had the option to be photographed and interviewed. Many individuals stopped and spoke with us, but some did not want their faces shown.

I had to come up with a creative way of photographing some of these subjects in a way that maintained their anonymity. Jared and I listened to each person as they told us their reasoning for making such a strenuous journey to the United States and the obstacles they faced during their journey.

I chose to shoot the portraits digitally, but also on film with a Hasselblad medium format camera. I then had the film digitally scanned and chose to showcase the film portraits over the digital originals because the film gave the portraits a sense of timelessness.

There was a lot of uncertainty and fear in the voices of the migrants, but also a sense of hope. I wanted the portraits to humanize a broad issue that often renders people as a statistic.

![Jacqueline, 38, from El Salvador, left home for the United States with only $70 dollars.

On her seven-month journey, she was kidnapped by narcos in Mexico and put to work for two and a half months in the city of Champas. She only said escaped with the help of several men from a nearby church. “A miracle from God” was how she summed up her arrival in the United States. In El Salvador, she was a shopkeeper, selling shoes and clothes back home to support her three children. Once a gang began to extort her for money, it was only three months before she had to close her shop. When she fled, she left much of her money with her three children. She said she constantly worries about their safety back home. “I need to bring my kids [here],” Jacqueline said, tears streaming down her face. “I need to work. I need to do something for them.”](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/ETCOwwLgG93B9UCIOTOVIA--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTk0Ng--/https://media.zenfs.com/en-us/usa_today_news_641/d6be39b4c6f49a2ea4bf550a9f3602c1)

More in this series

What happens to migrant children detained by the US government? One immigrant's story

How the USA TODAY Network spent a week reporting on the border to learn more about migrants

More migrants arrive from Guatemala than anywhere else. A dangerous flower is partly to blame

Local governments spend millions caring for migrants dumped by Trump's Border Patrol

US border crisis: Who are the migrants, why are they coming and where are they from?

Under surveillance: The lives of asylum-seekers and undocumented immigrants in the US

Is President Trump provoking illegal immigration by cutting aid to Central America?

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: I spent a day in LA immigration court, these powerful portraits tell the story