Like Utah, California has had pipeline dreams to save its drying Salton Sea

This article is published through the Great Salt Lake Collaborative, a solutions journalism initiative that partners news, education and media organizations to help inform people about the plight of the Great Salt Lake — and what can be done to make a difference before it is too late. Read all of our stories at greatsaltlakenews.org.

Most people don’t know that California’s largest lake — the Salton Sea — was a mishap.

Birthed in 1905 when the Colorado River experienced massive floods, the accidental lake soon became a community commodity. It once was a recreation destination, filled with fish and migratory birds, that supported the surrounding agricultural communities throughout the Imperial and Coachella valleys.

“Even in the last 10 years, the changes that have taken place have been pretty dramatic,” said Patrick O’Dowd, the executive director of the Salton Sea Authority. “The types of birds that frequent the sea have changed. The water level has changed. The water quality has changed.”

Other than its origin story, the Salton Sea and Utah’s Great Salt Lake share some commonalities. Both are drying terminal lakes hurt by the West’s drought and where water is siphoned off for human needs before water levels can replenish. In both places, dust is a consequence of the exposed lakebeds — and both have a pungent aroma. The ecological, environmental, and in Utah’s case, economic, impacts of the lakes’ declines have pushed both states into varying degrees of action to save them.

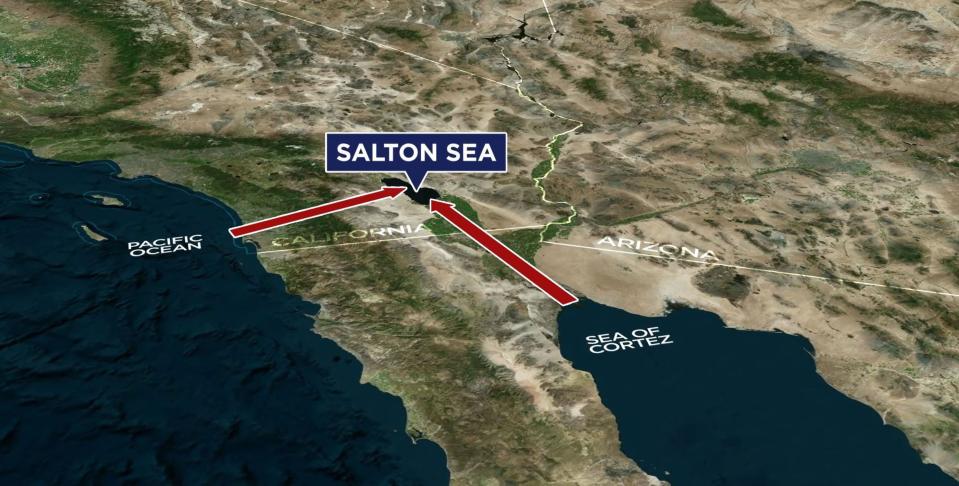

As more water is sucked out of the Salton Sea than replenished, Californians are looking for solutions. One of those lofty ideas is to build a canal or pipeline from the Sea of Cortez in Mexico to shepherd water to the ailing terminal lake — a different version of the pipeline ideas that have been floated in Utah.

The Sea of Cortez, otherwise known as the Gulf of California, is 125 miles south of the Salton Sea. From an engineering standpoint, it would be fairly easy to funnel ocean water to the depleted lake because it “would flow here naturally by gravity” thanks to the difference in sea level, O’Dowd said.

O’Dowd doesn’t “discourage its pursuit” because it’s “almost certainly achievable.” It’s more of a question of if it’s practical.

The Salton Sea is twice as salty as the ocean. Officials would need to invest in infrastructure to desalinate the ocean water because it would otherwise increase lake salinity, making it even more inhabitable. Additionally, there’s a question of where the money to construct and maintain the pipeline would come from. A 2022 independent review of the concept estimated it would cost billions to complete.

“The technologies that might make a seawater importation project feasible haven’t been invented yet,” O’Dowd said. “So we’re having to deal with tomorrow’s problems with today’s dollars and today’s technology.”

That same study, conducted by the University of California Santa Cruz, rejected the pipeline proposal for the Salton Sea. But that didn’t end the discussion. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers has plans for a three-year feasibility study on filling the lake, which includes exploring the pipeline idea.

The Salton Sea Coalition, an advocate in favor of the pipeline, believes it’s a viable option. Coalition member Chuck Parker thinks it would solve the most pressing problem: dust and the health impacts associated with it.

“The only way to prevent that is to refill it (the Salton Sea) with water,” he said.

Parker believes it’s worth the potential billions of investment because the state and local governments are “probably going to spend enough money on these little band-aid projects over 50 years.”

“It’s just there’s no, there’s no leadership. There’s no political will to. Let’s get the money together and do this.”

Tom Sephton, president of Sephton Water Technology, a desalination company, isn’t convinced the project would cost billions of dollars as the previous independent study projected. The construction of a canal and not a pipeline, Sephton said, would cost “a little over $1 billion.”

While he is confident importing water would reverse some of the negative effects of the ailing Salton Sea, Sephton acknowledges it wouldn’t return the lake to its glory days.

“You can’t turn back the clock. What you can do, however, is make a plan to create something that restores wildlife and at the same time restores an environment for wildlife (and) is a safe place for people to live and work.”

Sephton said his canal proposal has faced “fierce opposition” from public agencies, and it’s been a struggle to convince officials “that the people here are worth protecting, the environment is worth restoring, and the Salton Sea is worth saving.”

The difference between the Salton Sea and Great Salt Lake, Sephton said, is there is “much greater political will in Utah” to address the shrinking lake.

“Great Salt Lake is part of the cultural history and definition of the state,” he said.

Utah’s federal delegation has sponsored and supported legislation that allocates money to study solutions, including a pipeline. But a pipeline is not a simple solution — at least not for a landlocked state like Utah.

“You’ve got to pump water up much more elevation. You have to go over multiple mountains,” Sephton said. “It is going to be much more difficult and expensive, but that does not make it impossible.”

Despite the economic and geographical hurdles, Great Salt Lake Commissioner Brian Steed said water imports are still on the table. Importing water “would solve a lot of problems,” Steed told KUER’s “RadioWest,” but it’s unknown where the water would come from because “water in the West is a precious resource.”

And if water isn’t readily available to bring to the Great Salt Lake now, Steed told reporters during a Great Salt Lake question and answer session on Feb. 7, “then we really have to focus on what we can focus on, which is the conservation efforts.”

It would also take years to get a pipeline up and running and it’s unclear if the lake has that much time.

Charlie Diamond and Caroline Hung, both researchers with the Salton Sea Task Force at the University of California Riverside, note that “engineered” solutions are necessary to rehabilitate the Salton Sea. However, they are skeptical that ocean water is the best option. They’re more concerned with the sea’s water quality, since its primary source is agricultural run-off, which includes “additional salinity, nutrients and other pollutants.”

Ocean water doesn’t solve “the root problems,” Hung said. In other words, even if a pipeline filled the Salton Sea to healthy levels, there’s still a question of whether ecosystems could survive because of the excessive agricultural nutrients in the water.

“So just adding sea water and not treating the agricultural return flow won’t improve the problem of water quality that makes it unlivable for species and decreases the quality of life for communities nearby,” she said.

To Diamond, the idea of a Salton Sea pipeline is a “very highly engineered band-aid.”

Contributing: Alex Cabrero, KSL-TV