Utah’s clawing way out of an extreme water deficit. Will it last?

It was with some pleasure Gene Shawcroft, chairman of the Colorado River Authority of Utah, was able to point to a stop sign buried under nine feet of snow at a high mountain pass.

It was only discovered after a snow machine hit it, so a scraggly bit of vegetation was placed next to it to warn others of its presence.

As he detailed a presentation to members of the Federalism Commission Tuesday, he showed a slide depicting a vent pipe from a Forest Service outhouse barely poking out of the snow at Bald Mountain Pass in Duchesne County.

This, he told them, is what the Upper Colorado River Basin needed to desperately see last winter, and it did. The trick is if it will happen again this year.

“We’re not still anywhere close to being out of the woods,” said Shawcroft, who also serves as the general manager of the Central Utah Water Conservancy District.

In that extremely dry year from August 2021 to August 2022, system storage dropped to 34%, or the loss of nearly four million acre-feet of water in the Upper Colorado River Basin. To put that in perspective, an acre-foot is enough to cover a football field by a foot of water and is roughly enough to serve one water-wise household.

Related

Drought intensifies in Utah and the West amid searing heat, no rain

Anatomy of a drought: How the West may change for decades to come

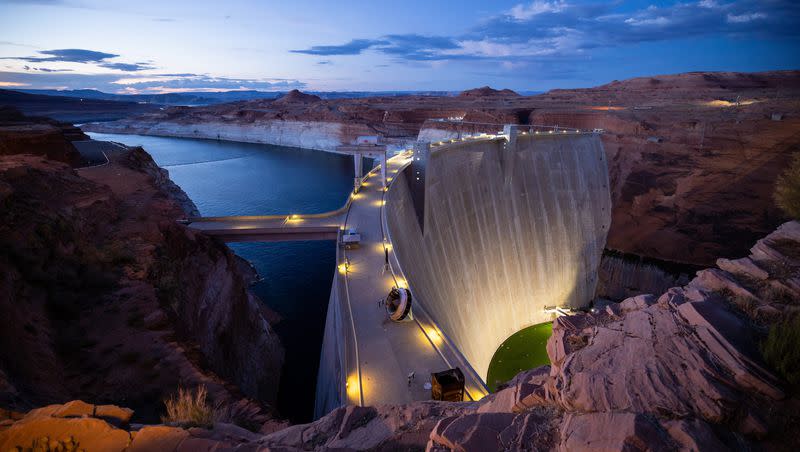

The situation at Glen Canyon Dam at Lake Powell was critical, hovering near an elevation of 3,490 feet which means dead pool and power generation from the dam no longer happens.

Hydroelectric power produced by the dam’s eight generators helps meet the electrical needs of the West’s rapidly growing population. With a total capacity of 1,320 megawatts, Glen Canyon produces around five billion kilowatt-hours of hydroelectric power annually which is distributed by the Western Area Power Administration to Wyoming, Utah, Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada and Nebraska. In the immediate vicinity, without the dam, the lights in Page would go dark.

“Elevations are critical,” Shawcroft said. “If the elevation gets below that there is no capacity to generate power. And there’s the question of whether or not we can make deliveries downstream because the (equipment) is what allows it to push water through the pipe.”

Drastic measures

The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, the Upper Colorado Basin states and, for that matter, the Lower Basin states, Shawcroft added, scrambled to bring resolution.

Through a series of complex water management steps, decisions were made to release water from upstream Flaming Gorge and Blue Mesa to keep the water flowing, delivering 1.6 million acre-feet of water to the ailing Lake Powell.

“If that would not have happened, we would have not been at power pool,” he told members of the Federalism Commission. “That’s how critical things were.”

With that incredible winter, steps were taken to replenish Flaming Gorge so it can overcome a deficit of 436,000 acre-feet, he added.

Against the backdrop of the lingering drought, the bureau remains convinced the states do not have the tools or political will to meet sustainable operational guidelines for the Colorado River, which has been described as the “Workhorse of the West.”

Whether a blessing or a curse, the river’s allocations were decided in a compact forged more than 100 years ago. It was the first time that so many states had come to a tenuous agreement that was reached via complex negotiations over a river’s resources and it was later endorsed under federal law.

Related

Now, states and the bureau are dealing with a new reality in a different century.

The bureau last year proposed severe cuts to the lower basin states that include Arizona and Nevada. And California — by far the river’s largest consumer — may have been on the hook as well.

States came up with their own plans, however, taking even deeper cuts while the bureau continues to work on a temporary plan to keep the river flowing until permanent operational guidelines are slated in 2026.

Related

The drying Colorado River needs your voice. Here’s how to make it heard

Feds propose cutting Colorado River water to California, Nevada and Arizona by up to one-fourth

The bureau, Shawcroft added, is still pursuing its course of action in which a draft of that plan will be released by the end of the month. After that, states have 45 days to weigh in.

What saved the entire basin this last summer is that bountiful snowpack.

Shawcroft said he checked the data the other day, and the reservoirs in the Upper Colorado River Basin were sitting at a combined storage of 82%.

“A year ago, it wasn’t probably even at 50%.”

A winter of hope

When forecasters were looking at what might happen this last water season, they were looking at scenarios in the 65% of normal range for snowpack, Shawcroft said. In a best case scenario, it sat at about 120% of normal and “maximum” probable was 121%.

Mother Nature, however, delivered 142% of normal for the Upper Basin states.

That, Shawcroft said, is what they’re hoping to see for this season, although being in the 180% of normal would be even better.

“That is what I would like to see,” he said, adding it is tough to manage such a complex river system based on unpredictable forecasts, which means there are possibly more changes in store.

The U.S. Drought Monitor says 100% of the Colorado River Basin is expected to see a probability of above normal precipitation this month, so at least that is a start.