Uvalde, Texas shooting: I dropped my kids off at school today, hoping I will see them again

Today, Wednesday, May 25, was rough.

There was nothing unusual about it, really. No backtalk from my 10-year-old or procrastination from my 6-year-old or even a meltdown from my 5-year-old. On any other day, that would be considered a miracle.

Today, though, I had to drop them off at their elementary school. I had the overwhelming impulse to turn the car around and just call them out for the day, take the day off work and cuddle with them.

But I couldn't. Because my 6-year-old had a field trip she had been looking forward to for weeks. And my youngest had to get her second COVID-19 vaccination. And my oldest had a doctor appointment in the middle of the day.

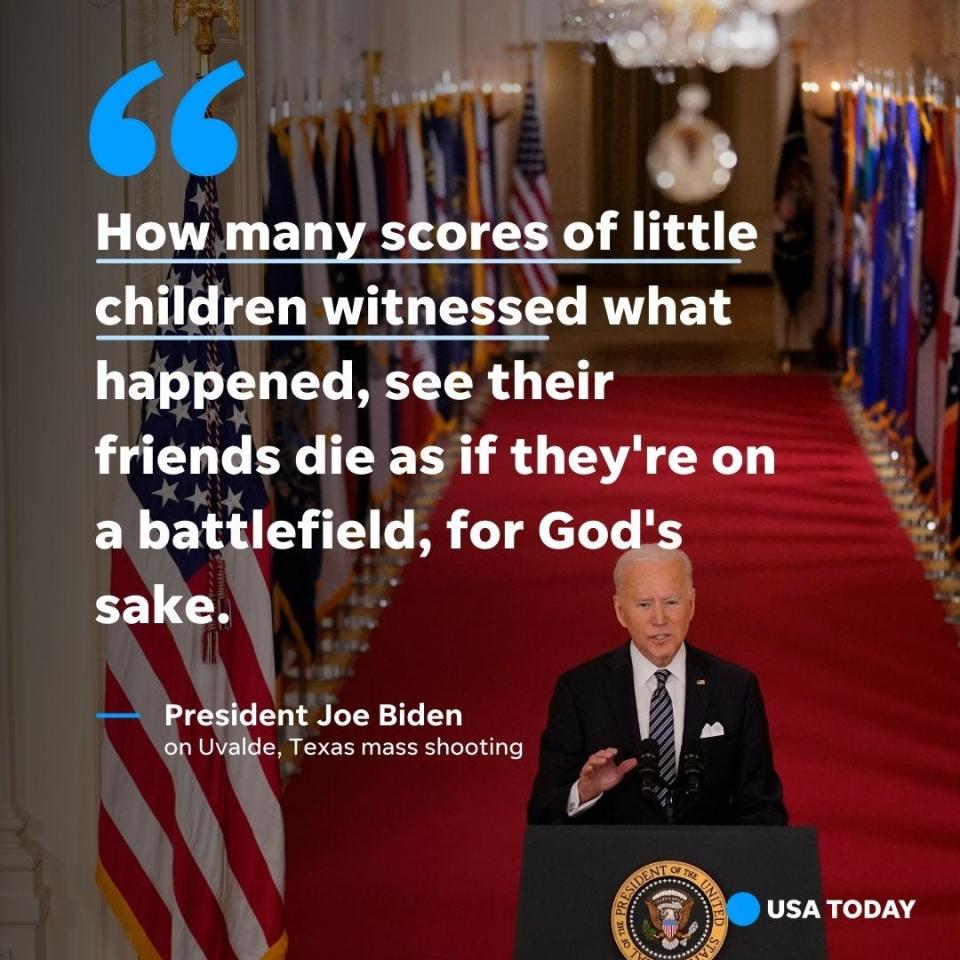

Despite the tragic events of yet another school shooting in the United States — this time at an elementary school in Uvalde, Texas, that left 19 children and two teachers dead — I had to wake up this morning and pretend that everything is fine. And tamp down the maddening knowledge that it is not, in fact, fine at all.

I've gotten pretty good at compartmentalizing, most likely my brain's defense mechanism at dealing with childhood trauma.

I was raised by a single mother who I didn't get to spend much time with when she was pulling 12-hour overnight shifts at Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit. I was an only child, and often left to my own devices with other family to watch me. That led to being a victim of sexual abuse and a devastating experience for my family when law enforcement and courts finally got involved.

Not long after that, my mother was diagnosed with cancer and died within 18 months. I was 15 years old.

Believe me when I say I learned quickly how to survive many brutal realities children all too often experience in this world we live in. In many ways, it served as a strength later, as I found my calling in the world of journalism.

We are often called to witness, report and interpret many unpleasant things to our readers. We must have the capability to observe and not be overly affected. We must be able to tap into compassion, empathy, triumph and tragedy — but not to allow those emotions to override our rationale.

Life made sure I was custom-made for this industry.

I realized it first on the morning of Sept. 11, 2001, when I was the editor of my student newspaper at Central Michigan University. As the students on staff were struggling to control their panic, fear, confusion and grief (all completely natural reactions), I was calmly organizing meetings, talking through communication plans and guiding them to focus on what we could do to help people find answers quickly.

I'm not a sociopath, I promise. Once the paper was "put to bed" that night, I was driving home and had to pull over on the highway as the devastating emotions I held back all day barreled through me, nearly crippling me with grief. I wept that day. For people I didn't know. For all those stolen lives. For what little innocence we had left as a country that was ripped away.

And so it went for future local and national tragedies. I could be heart-broken for those affected, but maintain a composed distance.

I was appropriately shocked with the nation when Columbine happened. I couldn't believe in my lifetime an incident like Virginia Tech occurred.

The cracks in the facade didn't really appear until Dec. 14, 2012. As I posted a story on our website about how a deeply unstable man shot and killed 26 people — including 20 6- and 7-year-olds — in Newtown, Connecticut, I was startled by the tears streaming down my face.

As my first child, then only 11 months old, played nearby completely oblivious to his mother's turmoil, I felt the inescapable realization that this could have happened to him. To us. It was possible that my child could one day be shot in his elementary school. Before that, it wasn't even a possibility in my mind.

Subscribe: Get unlimited access to our local coverage

Then came Parkland. I couldn't keep rationalizing these away as tragic isolated incidents. As the nation's leaders argued about arming teachers to fend off automatic weapon assaults, I was nervously sending my 6-year-old to first grade and hoping nothing like this would ever happen in West Michigan.

Then COVID-19 came and a different threat arrived with it. Do I send them to school with the chance they could contract a deadly virus we knew little about? How do I weigh my obligation to them to make them well-rounded, educated people who can successfully socialize with their peers while in equal measure keep them safe from a disease that hadn't even been on the Earth for a full year?

Then came Oxford and my walls crumbled completely. While weathering the COVID-19 exposures (three times last fall), I also had the joy of three days canceled over threats of violence to the district. In no way do I feel like my children are safe now.

I realize now that my childhood traumas, while awful to experience (and I don't share them with you lightly), were isolated situations that could be attributed to bad people and bad luck. Despite everything I had seen by the time I was 18, I can safely say my mother never had to worry that I would be murdered on any given day at my school. Or contract a virus that could kill me. In some ways, I'm luckier than my own kids.

Our children today live with open-ended threats to their lives — and they don't even know it. It's not one bad person to fear or the long-shot odds of the genetic lottery to fret about: It's a culture crippled by twisted political discourse and too many people afraid to have real conversations about real problems to find real solutions.

Which brings me to today. More babies snuffed out this week. They were taken before they even had a chance to make their mark.

I feel incredible guilt that I have my babies while those parents don't. I feel incredible anxiety sending them off like it's a normal day when they can't possible understand the risks they take every day simply taking the bus to school.

I can't wrap them in bubble-wrap. I also can't allow it to overrule my reasoning, although that is getting more difficult each week, month and year of my children being of school age. Even as I write this, I am fighting the urge to drive to the school to check on them.

Today was rough. And there will be more days like it to come. Because our country won't take any quantitative steps to stop this from happening. I simply have to cross my fingers that today, they will be alright and cross them again tomorrow.

As a citizen, as a journalist, and most importantly as a mother, that is unacceptable. And I'm not sure how much more parents like me can take.

— Sarah Leach is executive editor of the Holland and Petoskey groups for Gannett Michigan. Contact her at sarah.leach@hollandsentinel.com or @SentinelLeach.

This article originally appeared on The Holland Sentinel: Uvalde, Texas shooting: Leach: how much more stress parents can take