A UW-Madison building’s namesake supported eugenics. Campus reckons with legacy of Charles Van Hise

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

A history lesson may soon be attached to one of the tallest buildings in Madison.

The University of Wisconsin-Madison is moving forward with the installation of a plaque in Van Hise Hall that would explain the legacy of the building's namesake, Charles Van Hise, and his promotion of eugenics.

Eugenics is selective breeding, often by forced sterilization, to remove "undesirables" from society, such as people of color and those with disabilities.

The intent of the plaque is to spark a broader conversation about a relatively unknown and painful chapter in state history, and the university's role in it, said Kacie Luccini Butcher, director of the UW-Madison Public History Project who conducted research on the topic.

Who was Charles Van Hise?

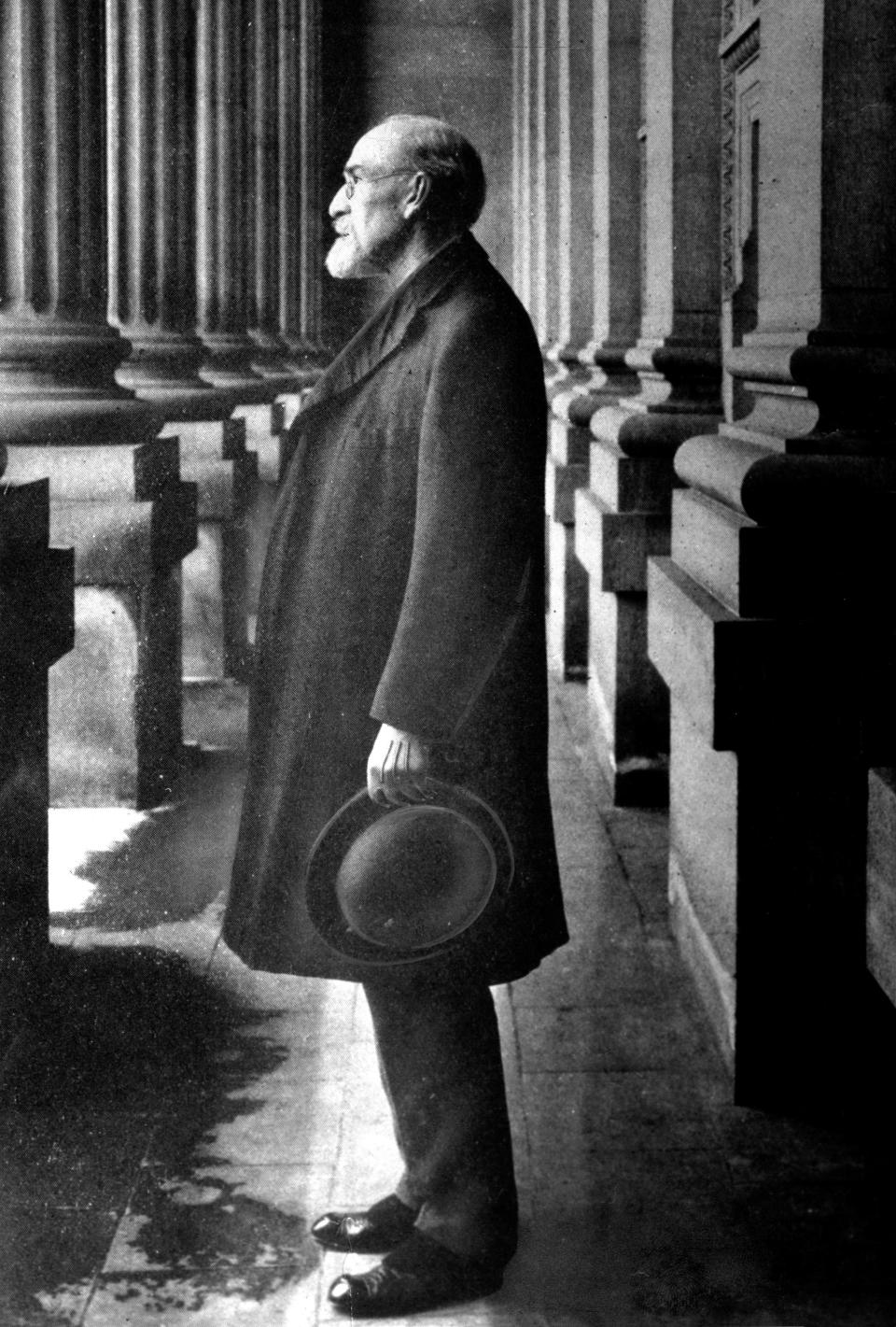

Van Hise received four degrees from UW-Madison, including the first Ph.D. degree granted by the university. He is the university's longest serving leader, serving as president from 1903 until his death in 1918. During his tenure, UW-Madison established a graduate division, founded a medical school and increased its faculty from 200 to 750 professors.

Van Hise is most remembered for working with a former classmate, Robert La Follette, to develop the Wisconsin Idea, the principle that the university should serve the entire state.

Van Hise advocated for eugenics

Less known is Van Hise's vocal promotion of eugenics. His interest in it came from reading Charles Darwin's book, "On the Origin of Species." Letters between Van Hise and his wife show he was curious about how to apply the ideas of animal evolution and natural selection to the human race, according to Luccini Butcher.

Van Hise lectured on eugenics, gave public speeches and talked to legislators. In one of his speeches, he said “[h]uman defectives should no longer be allowed to propagate the race" and sterilization "might be the proper method."

In another speech, Van Hise said “[w]e know enough about the breeding of animals so that if that knowledge were applied to man, the feeble minded would disappear in a generation, and the insane and criminal class be reduced to a small fraction of their present numbers.”

Most students are unaware of this part of Van Hise's history, Luccini Butcher said.

Wisconsin was a national leader in eugenics

Van Hise wasn't the only academic espousing eugenics during this time. Edward Ross, a UW-Madison sociologist, also advanced the idea.

UW-Madison in 1910 established the country's first department of experimental breeding, which was initially led by Leon Cole, another eugenicist. The department is today called the genetics department.

Academics gave the eugenics movement legitimacy and helped drive the Wisconsin sterilization law passed in 1913. The law forced sterilization for "undesirables" at the discretion of medical professionals. The state conducted nearly 2,000 sterilizations, the 11th highest in the country.

"These people have a ton of credibility," Luccini Butcher said of academics like Van Hise. "It's their great minds who are saying this is actually sound science."

Wisconsin repealed its sterilization law in 1978.

Eugenics was not widely supported when the law was in place, Luccini Butcher said. Many people saw it as an overstepping by the state. The Catholic Church, in particular, opposed forced sterilization.

Chancellor supports plaque

UW-Madison Chancellor Jennifer Mnookin supports the plaque and expects to finalize plans by the end of the semester, university spokesperson John Lucas said.

"UW-Madison acknowledges the complicated legacy of Charles Van Hise, who played an important role in the history of the institution, but also held views, especially around the field of eugenics, that are abhorrent to us today," Lucas said. The campus community over the last year has "carefully considered how it might both recognize Van Hise’s complex history and encourage engagement with, rather than erasure of, the past."

Proposed plaque is short

The six-sentence bronze plaque approved last week by the campus planning committee would read:

"Charles Van Hise was a Professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison from 1879 to 1903, after which he served as President until 1918. As President, Van Hise offered the best-known articulation of the Wisconsin Idea. He was also an advocate of eugenics. Eugenicists seek to justify discrimination against marginalized people whom they deem unfit based on individual and group characteristics and identities. The impact of eugenics can be seen not only in the genocides of the 20th century but also, for example, in discriminatory immigration practices and involuntary sterilization laws. As UW-Madison strives to serve the people of Wisconsin and the world, the legacy of Van Hise reminds us that we must acknowledge and grapple with all parts of our past and our present to move forward together."

A QR code may be included on the plaque, which could be scanned with a smartphone to take people to a website where they could learn more.

Why doesn't UW-Madison rename Van Hise Hall?

A faculty committee focused on disability access and inclusion considered renaming the 19-story building constructed in the 1960s. But the Van Hise name is everywhere in Madison, including on an elementary school, a street and a university teaching award.

The committee concluded in its most recent annual report that a plaque inside the bulding's first-floor lobby would be a better approach.

If the goal is education, renaming is often a missed opportunity, Luccini Butcher said.

"What will happen in a renaming debate, and what has happened before, is that you will take the name down, there'll be a kind of big backlash or controversy and lots of people will talk about it for a year or two or three, and then it kind of fades away, right?" she said. You get a whole new group of students or a new group of community members, and nobody remembers what the building used to be called, or nobody remembers that the monument was up."

Contact Kelly Meyerhofer at kmeyerhofer@gannett.com or 414-223-5168. Follow her on X (Twitter) at @KellyMeyerhofer.

This article originally appeared on Milwaukee Journal Sentinel: University of Wisconsin-Madison to add plaque to Van Hise Hall