Valerie Harper's death reminded me of my rant about 'Rhoda' and the great response I got

It was 1975 and I was upset. Rhoda had just gotten married and suddenly her career seemed to have disappeared. It wasn’t as if being a free-lance window dresser was an inflexible, 24/7 job, and she didn’t even have any children to keep her busy at home. And yet she was getting subsumed into her marriage to Joe.

It’s true that Rhoda was a fictional character in a TV sitcom, but that made no difference to me. In fact it made it worse in a way: Here was a story that could be told any way the writers wanted, and my hopes for a feminist heroine were fading.

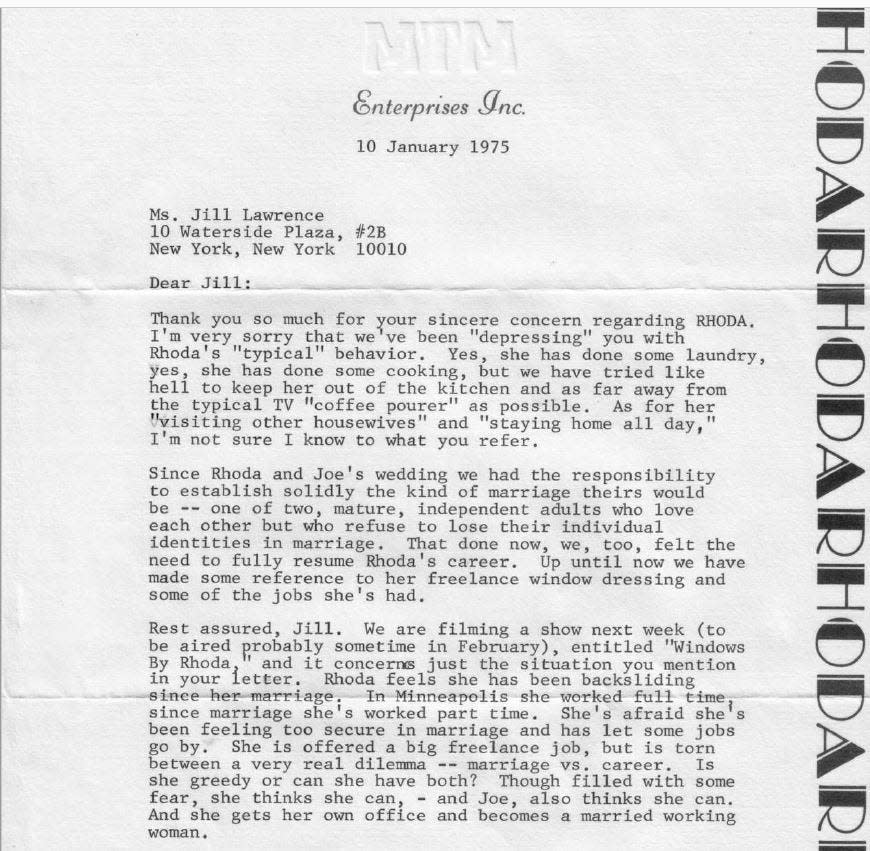

What happened next reveals so much about a time many women today can’t fathom: I typed an earnest, frustrated letter to the "Rhoda" show and received an earnest, frustrated reply from an "executive script consultant" named Charlotte Brown. Also typewritten.

Rhoda's career was 'backsliding'

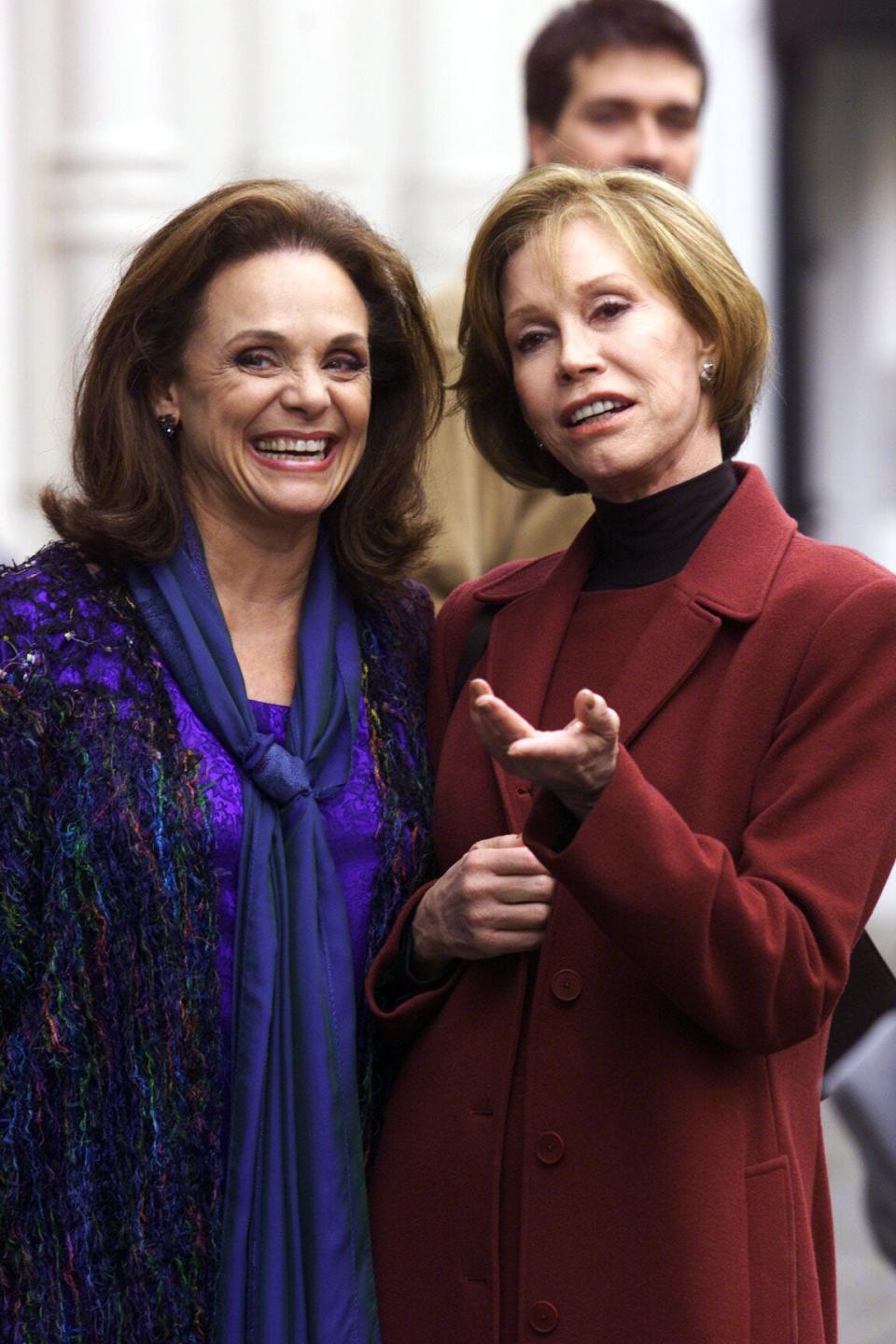

All this resurfaced like a message in a bottle with the death of Valerie Harper, the star of "Rhoda."

“Thank you so much for your sincere concern regarding RHODA,” Brown wrote. “I’m very sorry that we’ve been ‘depressing’ you with Rhoda’s ‘typical’ behavior. Yes, she has done some laundry, yes, she has done some cooking, but we have tried like hell to keep her out of the kitchen."

The letter goes on to explain the responsibility the show felt to define Rhoda’s new marriage as two people “who love each other but who refuse to lose their individual identities in marriage.” Brown went on, “Rest assured, Jill. We are filming a show next week … and it concerns just the situation you mention in your letter.” That is, Rhoda’s concern about “backsliding” in her career.

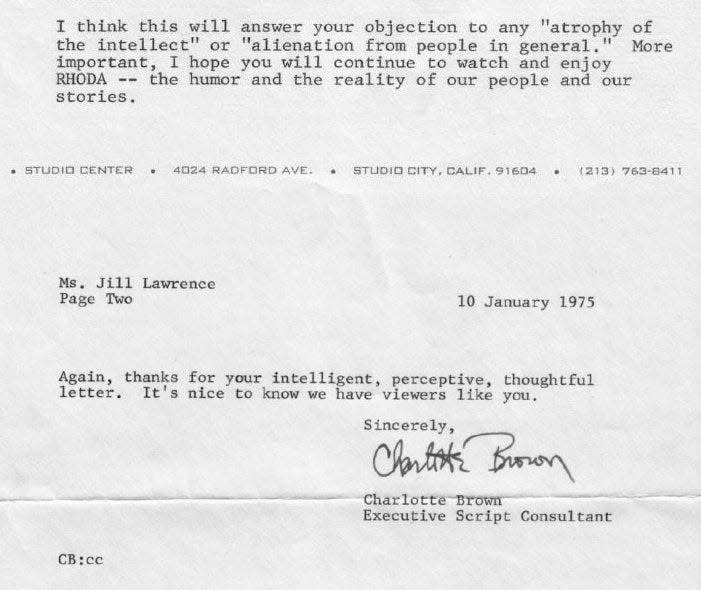

“I think this will answer your objection to any ‘atrophy of the intellect’ or ‘alienation from people in general,’ ” Brown said, and thanked me for watching.

I don’t have my own letter, but this and other sections of Brown’s response make my mood and tone pretty clear: young, annoyed, fiercely feminist and extremely disappointed.

The 1970s 'Squad' wimps out

Why was I so put out? Twitter user Freddie Johnson got at part of it when he said of a photo of Mary Tyler Moore, Valerie Harper and Cloris Leachman, “In 1974, this was The Squad.” And The Squad, in my view, was wimping out.

March of women's progress: #MeToo and inclusion riders are great. But should I worry about my son?

Strange but true, young and not-so-young women, it was not always the norm for married women to work. And when they did, before changes over “the past several decades,” the Labor Department noted in 2011, “women's work outside of home and marriage was restricted to a handful of occupations such as domestic service, factory work, farm work and teaching.” It wasn’t until the very late 1960s that newspapers like The New York Times and Pittsburgh Post-Gazette stopped running separate male and female “help wanted” ads.

So it was unusual in the 1970s for women to work in a TV newsroom (like Mary Tyler Moore’s Mary Richards) or dressing windows (like Harper’s Rhoda). And it was especially revolutionary to see women like this on television. You need only look at the fare from the 1960s (with the possible exception of "Get Smart") to see what a departure these shows represented. In Moore’s role as a housewife during that decade on "The Dick Van Dyke Show," one of her revolutionary contributions apparently was wearing capri pants and flats at a time when most housewives still wore dresses and heels. At least on TV.

Letter writer was a feminist pioneer

Charlotte Brown, it turns out, was a full-fledged member of the 1970s Squad. “Virtually every series that I was hired to write on, I was the first woman the producer had ever hired,” she said in a WHOA! Network interview posted on YouTube, and the first woman in the writers' rooms “that wasn’t taking dictation or a lunch order.” Though she never checked it out, she said, "when I started producing 'Rhoda,' I was supposedly the first woman writer-producer of a multicamera comedy.”

Oscar nominee Regina King: My commitment to gender equality must only be the beginning

Brown is now 75 and no doubt has long forgotten the letter she wrote to an anxious young woman trying to escape a dead-end job and break into political journalism, another field that was not exactly overrun with women in 1975.

But America was on the cusp of a transformational era in the lives of women. Feminists like Brown and me and Valerie Harper were fortunate to be around at that moment, pushing for change and benefiting from the opportunities we helped create.

Jill Lawrence is the commentary editor of USA TODAY and author of "The Art of the Political Deal: How Congress Beat the Odds and Broke Through Gridlock." Follow her on Twitter: @JillDLawrence

You can read diverse opinions from our Board of Contributors and other writers on the Opinion front page, on Twitter @usatodayopinion and in our daily Opinion newsletter. To respond to a column, submit a comment to letters@usatoday.com.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Valerie Harper death: My 'Rhoda' rant drew historic feminist response