Valley fever killed my mom and brother. Without new drugs, it'll likely take me

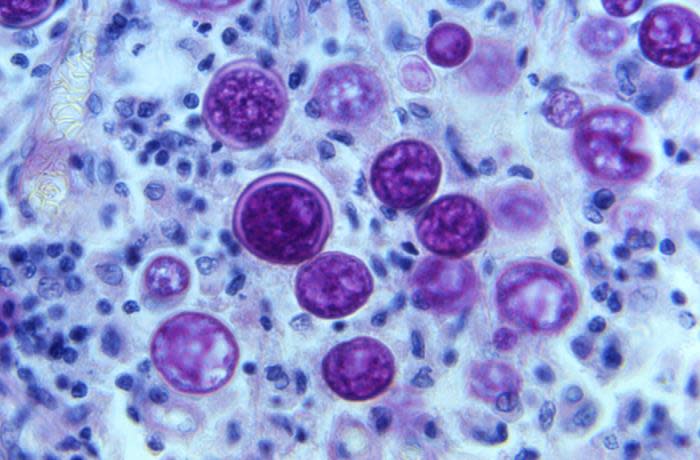

Arizonans face a uniquely high risk from the respiratory infection known as Valley fever. Contracted from airborne particles of the coccidioides fungus, which normally lives in the soil, the disease typically causes flu-like symptoms.

But while most cases remain mild, a few lead to pneumonia, meningitis and even death. At least five of my family members and I have contracted Valley fever. I’ve lost my mother and brother to it and will likely die of it myself.

Of the 20,000 reported U.S. Valley fever cases in 2019, more than two-thirds were in Arizona, where the heat and dust are particularly hospitable to the fungus. Wind and human activity like construction kick it up out of the ground.

You would think that elevated chance of exposure should motivate our federal lawmakers to help fight the disease, cases of which have risen steadily since 2014. I’ve not been wowed by the response to this increasing threat, but I am glad to see that the conversation is amping up and that there is a constructive path forward.

Drug resistance makes Valley fever hard to treat

Part of what makes Valley fever such a challenge is that the main way to treat moderate to severe cases – a course of antifungal medication like fluconazole – is steadily losing its effectiveness against some fungi. This is part of a wider crisis known as antimicrobial resistance, or AMR, in which certain microbes, known as “superbugs,” stop responding to the medicines we have to treat them.

Two existing bills could help solve the problem.

One, the PASTEUR Act, would create financial incentives for drug makers to develop new antibiotics and antifungals, which because they need to be used sparingly, don’t otherwise provide much return. The bill would establish a subscription model under which developers receive a fixed payment in return for supply, regardless of total quantity needed.

Another proposal, called the FORWARD Act and sponsored by Arizona’s Sen. Mark Kelly, would direct support to research on antifungal medicines, Valley fever in particular. The bill includes a requirement that the Food and Drug Administration fast-track the approval process for these treatments.

Battling dust:Residents near rock quarry struggle with Valley fever

Caused in part by overuse and misuse of antimicrobials, drug resistance is a massive and growing problem. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports nearly three million drug-resistant infections in the United States each year, leading to more than 35,000 deaths. Worldwide, antimicrobial-resistant bacteria killed 1.27 million people in 2019 and was a contributing factor in another 4.95 million deaths, making it deadlier than either HIV/AIDS or malaria.

This tragedy is taking an economic toll as well. Drug-resistant infections cost the United States about $55 billion each year in health expenses and lost productivity, according to the CDC. Here in the Grand Canyon state, the cost of Valley fever over the lifetime of infected Arizonans was estimated at $789 million in 2019. Worsening drug resistance could soon push that figure higher.

We need new medicines, and quick

The rise of superbugs is worrisome for many reasons.

They are particularly dangerous to people with chronic illnesses like diabetes, heart disease or cancer, who often need effective antibiotics simply to manage their health. In Arizona as well as nationwide, about 6 in 10 people are living with one chronic condition and 4 in 10 are living with two or more. Some 7 million immunocompromised American adults rely on antibiotics to keep infections at bay.

But AMR does not discriminate, and the reality is, everyone is at risk. Even the most routine medical treatments, like joint replacements and C-sections, will become far riskier if antimicrobial resistance continues to grow.

Thankfully, researchers, including many here in our state, are working to develop the next generation of antifungal and other antimicrobial drugs. Northern Arizona University’s Pathogen and Microbiome Institute, Arizona State University’s Biodesign Institute and the University of Arizona’s Valley Fever Center for Excellence are all making progress against superbugs.

Still, solving antimicrobial resistance is no small task. Preventing overuse and misuse of treatments via better drug stewardship could buy us some time. Less exposure will give dangerous microbes less opportunity to evolve into hardier versions of themselves.

But we also must fund research and development into the next generation of medicines – before our antimicrobials stop working altogether.

Both the PASTEUR Act and FORWARD Act would help provide a sustainable infrastructure for the development and delivery of novel antimicrobials to protect Arizonans.

More than two years later we are still navigating COVID-19, but by taking lessons learned to better prepare for another health crisis we would be making an essential investment in the people in Arizona and across the country. It certainly makes a lot of sense to me.

Pat White has been living with Valley fever for 17 years. She is the director of Education for Arizona Victims of Valley Fever, Inc. Reach her at pat-valleyfever@live.com.

This article originally appeared on Arizona Republic: Valley fever killed my mom. Without new drugs, it could take me