Vandalism, slurs and a resignation: Antisemitism storm hits Ivy League's 'friendliest' school for Jews

PHILADELPHIA – In the City of Brotherly Love, Gemma Levy sometimes doesn’t feel safe.

Levy decided to attend the University of Pennsylvania partly because of its long history of tolerance toward Jewish students like her. But with recent events – pro-Palestinian protests, antisemitic chants, university President Liz Magill’s perplexing remarks about genocide and her subsequent resignation – the campus hasn’t seemed all that tolerant.

“I’ve felt super-unsafe at times,” Levy, a freshman cognitive science major from Brooklyn, said while hurrying to class along the tree-lined Locust Walk in the oldest part of the campus. “It’s a weird experience to feel that way.”

It’s an unsettling experience for the city, too.

Philadelphia, known as the birthplace of the United States, is where the Founding Fathers met and debated the future of the new country. Founded on the principles of religious freedom, it’s home to one of the largest Jewish populations in the country.

The University of Pennsylvania, founded primarily by Benjamin Franklin and now regarded as one of the nation’s premier schools of higher learning, kept its doors open to Jewish students when Harvard and other Ivy League colleges implemented quotas and other measures to limit their enrollment or keep them out altogether.

Today, though, Philadelphia and the university are at the epicenter of the clash over free speech and antisemitism, the Israel-Hamas war and the right to feel safe and secure.

How did that happen? In Philadelphia of all places?

“We’re a microcosm of society,” said Michael Balaban, president and chief executive officer of the Jewish Federation of Greater Philadelphia.

Antisemitism is a virus that mutates over time and is easily spread through the prevalence of social media, Balaban said.

“We see it online in vicious ways every single second of the day.”

Choosing a college is hard: The Israel-Hamas war is making it harder

'Vile, antisemitic messages'

Antisemitism in Philadelphia has turned up online, on campus and in the streets.

In November, the university responded to what it described as “vile, antisemitic messages” threatening violence against the Jewish community. Antisemitic emails were sent to a number of staffers, and antisemitic language was projected onto several campus buildings. The school said it planned to increase security across the campus, including at Penn Hillel, a Jewish student organization.

A month later, an off-campus protest by pro-Palestinian demonstrators was widely condemned for targeting the Jewish-owned falafel restaurant Goldie. Video posted on social media showed a large crowd gathered outside the restaurant, chanting: “Goldie, Goldie, you can’t hide. We charge you with genocide.”

The Philadelphia Inquirer reported that the restaurant was singled out because its owner, Philadelphia-based Israeli chef Michael Solomonov, had raised more than $100,000 for an Israeli nonprofit that provided emergency relief services to Israeli soldiers after Hamas’ attack on Israel on Oct. 7.

The White House, Pennsylvania Gov. Josh Shapiro and others condemned the protesters’ actions, calling them antisemitic and reminiscent of a dark time in history.

Backlash: Harvard, Penn and MIT presidents ignite furor with 'unacceptable' response to antisemitism

Then came Magill’s downfall.

Magill and the presidents of two other elite universities – Claudine Gay of Harvard and Sally Kornbluth of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology – already had been under scrutiny over how their institutions had responded to a rise in antisemitism on their campuses when they agreed to testify last week before a GOP-led House congressional panel.

Lawmakers lobbed a series of tough questions at the three college leaders, who hedged when Rep. Elise Stefanik, R-N.Y., asked whether calls for the genocide of Jews violated their schools’ code of conduct against bullying and harassment.

Appearing to sense a trap, Magill and the other two presidents gave carefully worded responses that sounded scripted and lawyerly but failed to directly answer the question. In one exchange, Magill called those decisions “context-dependent” but conceded that calls for genocide could be considered harassment “if the speech turns into conduct.”

The backlash was fast and brutal. To some, the presidents’ responses raised questions about whether the schools would adequately protect Jewish students. The White House condemned their answers, donors threatened to withhold millions of dollars, and the House committee announced an investigation into the universities' policies and disciplinary procedures.

Magill tried to walk back her comments, but the damage was done. She resigned last Saturday but will remain at the university as a tenured law professor. Scott Bok, chairman of the university’s board of trustees, also stepped down.

Julie Platt, the trustees’ interim chair, declined requests for an interview but said in a statement after Magill’s resignation that a leadership change at the university was “necessary and appropriate.”

Though Penn has made strides in addressing the rise of antisemitism on campus, “we have not made all of the progress that we should have and intend to accomplish,” she said.

Magill, who had been president for just a little over a year, was on shaky ground even before her testimony. She had come under fire in September over a Palestinian writers festival at the university and drew criticism for including speakers who have been accused of antisemitism. Magill and others had raised concerns about the program but did not stop it, citing support for “the free exchange of ideas” – even those that are controversial and “incompatible with our institutional values.”

Last week, a pair of Jewish students sued the university, claiming it has become a lab for "virulent anti-Jewish hatred, harassment and discrimination."

Author Jerome Karabel, who has written about the history of exclusion at Ivy League schools, said it is ironic that Penn is facing accusations that it hasn’t done enough to quell antisemitism on campus. At some point, all of the other Ivy League schools tried to limit Jewish enrollment. Penn never had any such limitations, he said.

“You could argue that Penn, historically, has been the friendliest of the Ivy League schools for Jewish students,” Karabel said.

A new level of activism: Israel-Hamas war stirs free-speech battles at college campuses across US

'An inclusive and welcoming community for all students'

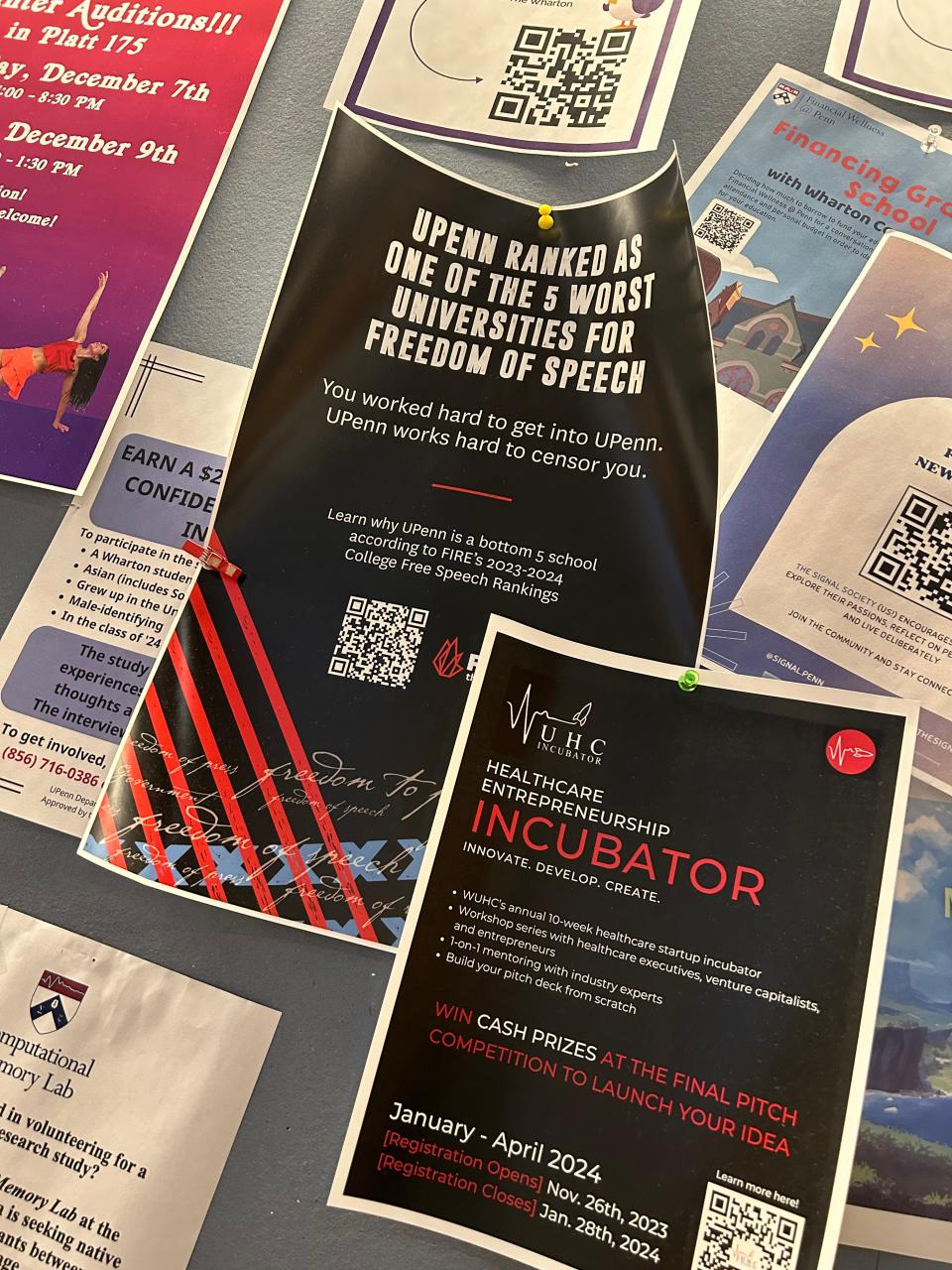

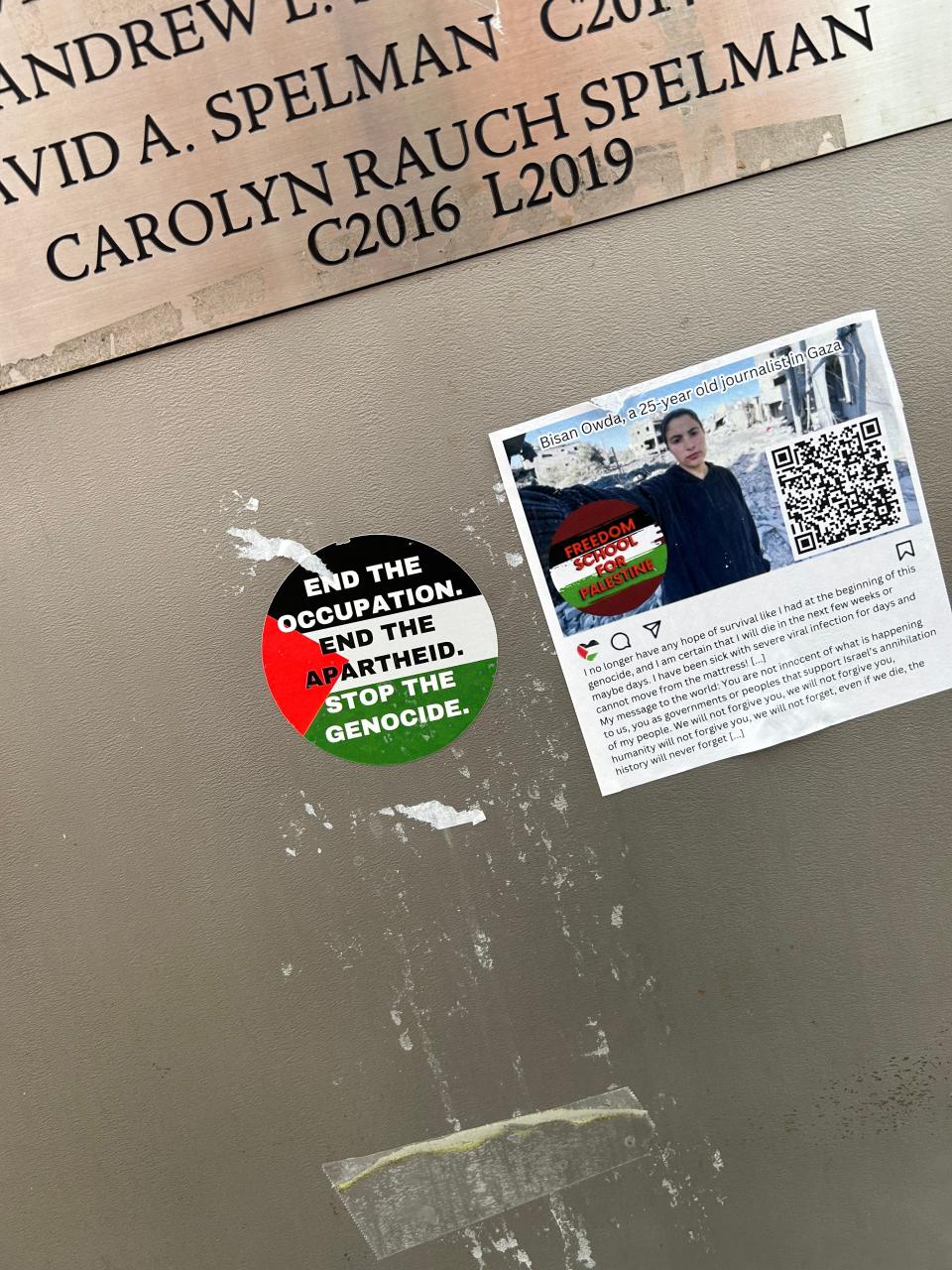

On campus, there were few outward signs of turmoil this week. With final exams under way, students hurried to class on a cold, blustery late-fall morning. Stickers and flyers supporting the Palestinian people and urging a cease-fire in the Israel-Hamas war were posted on billboards and along walkways and pedestrian bridges.

At Houston Hall, which the university says is the oldest student union in the country, a small group of students has been staging a sit-in since mid-November to show support for the Palestinians. Early one afternoon this week, protesters nestled in big chairs and slept under sheets on cushions. Others painted posters and flyers listing their demands: A cease-fire in the Gaza Strip. The protection of freedom of speech on campus. “Critical thought” on the subject of Palestine. A place for Palestinian studies.

“Nobody here is calling for the genocide of Jews,” insisted Clancy Murray, who is working on a Ph.D. in political science.

Murray said several Jewish students have joined the sit-in but acknowledged that some feel unsafe in the current environment. Some Palestinian students on campus aren’t comfortable being visible either, Murray said, because of threats and the possibility of doxing, harassment and even violence and hate crimes.

As for Magill’s departure, Murray said it’s concerning “that she was driven out” and that “there are a handful of donors who are empowered to dictate what is and what is not acceptable speech on campus.”

David Donovan, who was on his way to his daughter’s graduation from Penn’s nursing school, said emotions surrounding the Israel-Hamas war are charging tensions on campus like never before.

“We are more sensitive to the feelings of other people, and that’s a net positive, I believe,” said Donovan, a history teacher from Morristown, N.J.

When it comes to deciding what constitutes free speech versus hate speech, Donovan said, “we still have to be very apprehensive and think very carefully that our positions are backed by reason.”

“We need to err on the side of free speech,” Donovan added, acknowledging, “That’s an easy thing for me to believe as a straight, white man.”

The community at large is also grappling with issues of free speech. Some Jewish families are rethinking outward expressions of Judaism, Balaban said.

At his home in the Wynnewood suburb, Balaban flies both the Israeli and American flags in the front of his house and displays a menorah in the window. Before, “that would never have been a question in my mind to do it or not to do it,” he said. But with everything that has happened, “in my household, the question was, ‘Are we OK doing this?’” he said.

“Of course, the answer is, yes, we're going to,” Balaban said. “But did we worry that someone may do something? The answer is yes. I think we will always display an Israeli flag with pride. We will always display symbols of our Judaism. But there was a pause of what does that mean.”

'We will come through this difficult moment'

So what's next? How do the community and the university heal after the trauma of the past few months?

"This is a strong community built on a sturdy foundation. We will come through this difficult moment," the university promised in an email message to students this week.

The university pledged to redouble its commitment to ensuring that Penn is a place where “intellectual growth is cultivated” and students are “supported as a person.”

“Initiatives recently launched to address bigotry and hatred on our campus will continue, and this will be an inclusive and welcoming community for all students,” the message said.

Levy urged school administrators to be more proactive and less reactive.

“I hope,” she said, “instead of being on the defensive and apologizing after things happen, they’ll take steps to actually stop these incidents in the first place.”

Speech police? Supreme Court asked to enter fray on confronting bias on campus.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Antisemitism at Penn pushes city toward free speech reckoning