'Vast majority of Americans want to know': Author explores origins of eugenics in Vermont

The U.S. participation in eugenics – the pseudoscientific field predicated on the belief that humanity’s gene pool can be improved through selective breeding – remains opaque almost 100 years after the movement’s devastating heyday in pre-World War II era America.

Even Vermont, which boasts some of the most extensive records on the eugenics movement in the country and is one of the few states that has formally apologized for its participation, still has gaps to fill.

A new history book, released in Septmeber, provides a broader insight into Vermont's sordid past, dispelling many misconceptions residents may have about the scope and origins of eugenical practices in the Green Mountain State.

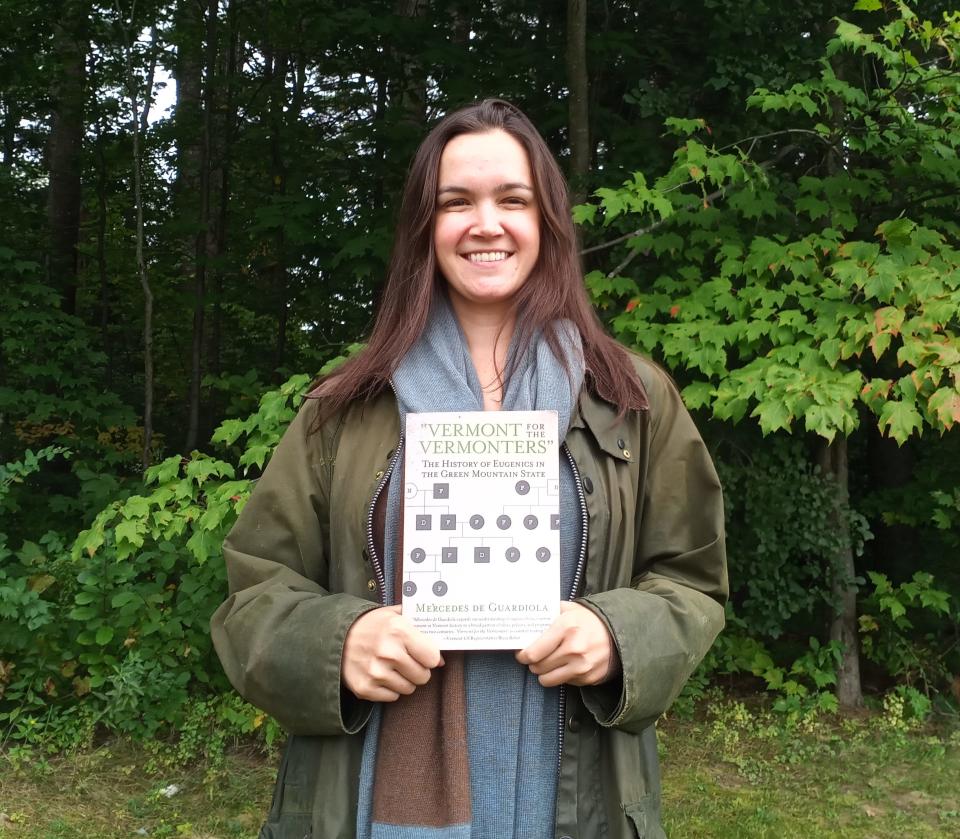

The book, aptly titled "Vermonters for the Vermonters": The History of Eugenics in the Green Mountain State, was written by historian Mercedes de Guardiola, whose testimonies in front of the state Legislature helped pave the way for a formal apology from lawmakers in 2021. De Guardiola's award-winning undergraduate research at Dartmouth College forms the book's foundation.

"The book examines how failing systems of healthcare and public welfare, coupled with pre-existing beliefs on human worth, exploded into support for eugenics," de Guardiola said.

Until now, most research about Vermont's eugenics movement had focused almost exclusively on the Eugenics Survey of Vermont (1925-1936) and the 1931 sterilization law, tools used to track bloodlines and prevent "genetically inferior" individuals (e.g. racial and ethnic minorities, the intellectually disabled, criminals, promiscuous women, the poor, etc.) from reproducing. While both pivotal moments in history, researchers' selective concentration on these two events "has led to (public) misunderstanding on why and how eugenics emerged in Vermont" and perpetuated the idea that public policies were limited to sterilization, de Guardiola said.

'Largely unable to eat': Man sues South Burlington dentist that leaves him without teeth

For this reason, the goal of de Guardiola's "Vermont for the Vermonters" is to elucidate the origins of the state's eugenics movement, all the ways it was practiced and why the general public not only tolerated but supported these efforts. Her research reveals an explicitly human explanation: the need for a scapegoat to explain emerging economic and societal issues.

"Vermont for the Vermonters" can be purchased through the Vermont Historical Society's website.

Origins of Vermont's eugenics movement

The premise behind eugenics − that some types of people are inferior to others and therefore should not exist − dates back to the dawn of mankind.

"In many cases, eugenicists did not reinvent the wheel, instead building onto existing laws, policies, and organizations," de Guardiola said. "We see this in their support for anti-miscegenation laws, joining forces with the 1920s Ku Klux Klan, and use of existing state institutions to carry out eugenical segregation."

However, the eugenics movement, which first became popular in the early 20th century, marked the first time humans attempted to use science to legitimize these beliefs.

Mercedes de Guardiola

Vermont government officials and scientists began advocating for eugenics policies as a solution for the state's recent economic and social hardship (e.g. population decline, brain drain, increased debt and poverty, overcrowding and underfunding of poor farms and state institutions, etc.), which they claimed resulted from a decline in Vermont's "old stock" − the highly mythologized versions of the men and women who founded the Green Mountain State.

"The resulting biased statistics and fundamental misunderstanding of the contributing factors, at hand, led a number of leading Vermonters to believe that the people sent there (to asylums and poor farms) were incurable and had poor heredity, and that eugenics offered a scientific and humane solution," de Guardiola said. "Their own existing personal convictions also predisposed them to not seriously interrogate this conclusion."

Not everyone was a major proponent of eugenical practices, however; some people simply had no other options.

"We have the letters from parents and guardians begging for institutions to take their loved ones because they did not have the means to care for them," de Guardiola said. "We know of requests for sterilizations where parents and guardians feared that a pregnancy would prevent full-time care or that their charge could not understand pregnancy."

What are some examples of eugenics in Vermont?

The eugenics movement in Vermont extended beyond forced sterilization, a policy most Vermonters typically think of in relation to eugenics. In fact, records indicate that "segregation through institutionalization" was much more commonplace, de Guardiola said, although documentation on sterilization is admittedly incomplete.

To prevent "degenerates" and the vaguely defined "feeble-minded" from reproducing, children and adults were locked away in Vermont's public and private institutions, including Waterbury Hospital, the Brandon Industrial School and the Reform School, otherwise known as either the Vermont Industrial School or the Weeks School.

"We also know that Vermont eugenicists pushed for eugenics through things such as marriages—both civil and religious ceremonies—education programs, and family separation," de Guardiola said, adding that proponents also had ties to the Ku Klux Klan, which experienced a resurgence in the 1920s.

Due to Vermont's overall racial and ethnic homogeneity, the populations Vermont eugenicists targeted differed slightly from other states.

In addition to people of color and immigrants, eugenicists pursued individuals and families who failed to adhere to cultural traditions (in this case "expectations of rural agricultural success") or moral norms, such as celibacy for unmarried women and girls, regardless of if abuse was involved. Other vulnerable groups included the impoverished and people with intellectual disabilities and mental and physical health problems.

Does eugenics and 'forced sterilization' still happen in the United States?

According to de Guardiola, eugenics never officially ended in the U.S., "it was simply reinvented."

After World War II, the term "eugenics" fell out of favor due to its association with Nazi Germany, but even so, eugenical policies did not necessarily disappear.

"The backlash that followed World War II and the public knowledge of Nazi Germany's horrors ruined the term 'eugenics' and forced American eugenicists to nominally disavow the term," de Guardiola said. "They quickly rebranded, with many joining fields such as genetics as eugenic policies remained in place, including institutionalization, marriage restrictions and anti-miscegenation laws, and sterilization."

Art, antisemitism and a woman's legacy: History causes modern controversy in Vermont

The omission of the term eugenics in post-war records has made tracking its legacy difficult and a definitive end to adjacent policies uncertain. Eugenicists instead had resorted to using "dog whistles" in documents, or language that only people highly familiar with the movement would understand as references to eugenical practices.

Even pre-war records sometimes hid intent.

"We know that in some cases, including through education campaigns, eugenicists encouraged the public to practice eugenics while deliberately hiding the eugenical reasoning," de Guardiola said.

Even though many Americans are appalled by the eugenics movement today, support for the ideology persists.

"Even today, eugenics support pops up here and there across the country, whether it's intermittent cases of sterilization, neo-Nazi rallies, or calls to have more 'desirable' humans procreate at higher rates," de Guardiola said.

What are the effects of the eugenics movement today?

Additionally, the consequences of the movement continue to be felt today. For instance, de Guardiola said that eugenics practices have contributed to contemporary problems such as the nationwide homeless crisis, the lack of sufficient long-term mental health treatment facilities, and skepticism of the medical system among some communities.

"Understanding how it contributed to these modern-day issues will be key to determining how we can avoid the issues of the past while building strong, humane responses and addressing intergenerational harm from eugenical policies designed to destroy families," de Guardiola said.

"Land sovereignty" fund: Black people own just 17 of the 7,000 farms in Vermont

Although "Vermont for the Vermonters" heavily expands what locals know about their history with eugenics, de Guardiola admits there is still much to learn about the movement due to incomplete and missing records and encourages other historians to keep digging.

"Most people do not realize how widespread and long-ranging American eugenics was," de Guardiola said. "I do believe the vast majority of Americans want to know what happened to people who were family, friends, and neighbors, and we're seeing that push to address eugenics today."

Megan Stewart is a government accountability reporter for the Burlington Free Press. Contact her at mstewartyounger@gannett.com.

This article originally appeared on Burlington Free Press: Vermont author's new book on eugenics reveals details, VT examples