Venezuela’s #MeToo movement finds its voice on social media as women share stories of abuse

The accusations that appeared on Twitter were alarming: A woman who identified herself as “Pia” said she’d been sexually abused by a prominent Venezuelan writer when she was 16.

“I thought I had found a mentor,” she wrote. “Some sort of paternal figure in whom I could trust my literary ambitions and that I would receive a guide.”

A day later, Willy McKey responded to the accusations on social media, acknowledging she was his “victim” and writing: “Don’t be this. It grows inside and it kills you. I’m sorry.”

Shortly after in April, authorities said he jumped to his death from the ninth floor of an apartment building in Buenos Aires, Argentina, where he had been living.

Nearly four years after the #MeToo movement set off a reckoning in the United States over sexual abuse against women, Venezuelans have begun taking to social media to share their own experiences, calling out well-known artists, politicians and even family members.

The flood of mostly women posting accounts of abuse began last month when an anonymous Instagram account started publishing the testimonies of women and underage girls who said they were sexually harassed and abused by members of local music bands.

Within days, Grammy award winner Linda Briceno, known as Ella Bric, founded a group called Yo Te Creo Venezuela — I Believe You Venezuela — to gather stories, organize victims and educate the public. Within a week, the group received 565 testimonies, 87 requests for psychological help and 26 seeking legal advice.

Human rights advocate Maria Corina Muskus said that women have turned to social media in part because of their distrust in Venezuela’s justice system. She said many women in Venezuela are living in an environment where violence is tolerated.

“Just because there are no complaints of abuse doesn’t mean there isn’t abuse taking place,” she said. “Usually it means that it’s normalized, that there are no mechanisms to complain.”

Young actresses point to theater director

Stephanie Cardone Fulop describes what is happening on social media as a “snowball effect,” in which years of harassment and abuse are now coming to the surface.

The actress based in Caracas took to Instagram in April to describe her experience with Juan Carlos Ogando, a director at a well-known theater group in Venezuela, after another woman spoke out with a similar account of abuse.

Cardone Fulop, 34, said they were about to premiere a play called “Mafiosical” in 2008 when he entered a dressing room and kissed her, which she perceived as a “huge abuse, because I didn’t have any kind of social, affectionate or educational relationship with him,” she wrote.

“I raise my voice to give visibility to what happened to me, to Andrea and the other girls. It’s not just the two of us, we’re well over 10 women,” she said, explaining that some of the other women who have since come forward are too scared to speak out.

Ogando has not been charged, but Venezuela’s chief prosecutor recently said his office has opened an investigation into the accusations. Ogando declined to comment, stating only that he is “working on the matter.”

Andrea González Cariello, 22, uploaded a video to her Instagram account last month describing how Ogando touched her inappropriately from the time she was 13 until she was 17 years old. She wanted to complain but said she was fearful that nothing would happen.

“I was scared,” she said. “Scared that things would stay the same, that it would be just words. But, thanks to all the girls that have started speaking up, I decided to do it too, so that no other girl has to go through what my classmates and I did.”

Shortly after both women came forward with their accounts, Ogando’s theater group announced he and the staff had “mutually agreed on his separation from the company.”

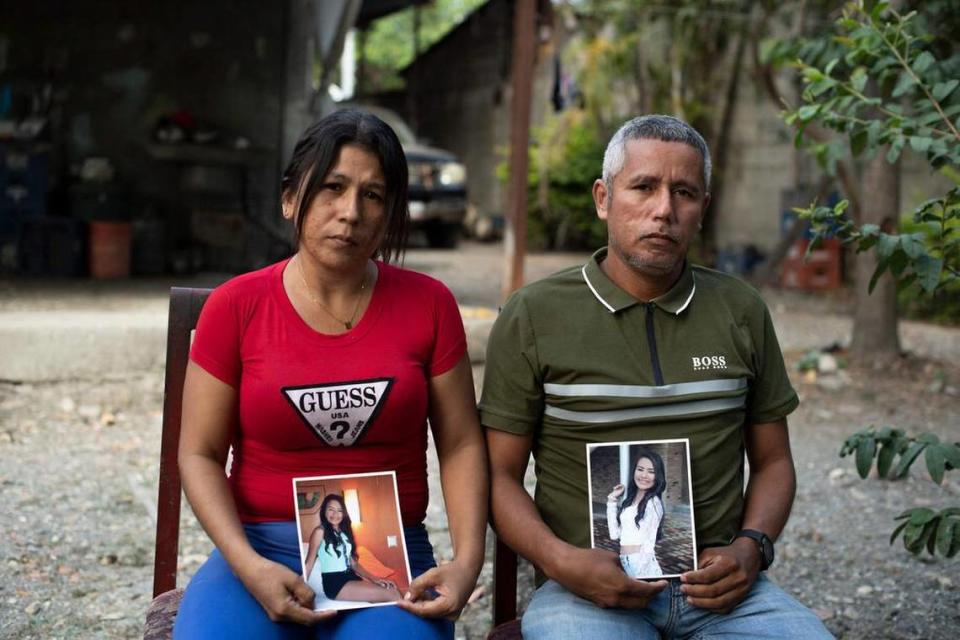

Femicides in Venezuela spark alarm

Lawyer Carolina Godoy said Venezuela’s legal system is missing opportunities to halt violence against women, often only acting when someone is killed.

“They focus attention on the last step of a chain of abuse, which is femicide,” she said, adding that if investigators paid more attention to other cases, the country would potentially see a decrease in murders.

Femicides in Venezuela rose from 167 in 2019 to 256 in 2020, according to a private initiative called Femicide Monitor, created by the digital platform Utopix. The group gathers accounts reported in local media because official statistics are not published. They have reported 73 femicides in Venezuela in the first four months of 2021.

Latin America is considered one of the most dangerous places in the world to be a woman. At least 4,555 women were victims of femicide in 2019, according to the Gender Equality Observatory at the United Nations’ Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean. Though more recent figures are not yet available, many individual cities and nations reported upticks in 2020, as pandemic lockdowns forced many women to stay in close quarters with their aggressors and made getting help harder.

Throughout the region, women have begun decrying abuse and demanding greater reproductive rights. Argentina became Latin America’s largest country to legalize elective abortion last December, a vote that was considered a victory for the nation’s feminist movement. Some anticipate it could lead to similar laws in a region that is heavily Roman Catholic and socially conservative.

In Venezuela, abortion is still a crime in nearly all cases. The country’s new activists are calling attention to a range of issues, from daily harassment on public transportation to sex crimes.

Venezuela accusations signal harassment across industries

Outside of the entertainment industry, Venezuelan women and men have shared stories of abuse involving everyone from politicians to romantic partners and relatives.

Marcel López, a lawyer who now lives in Chile, accused a politician with a prominent opposition party of taking advantage of young men, promising to help their careers. He said the stigma that accompanies being gay in Venezuela made coming forward even more difficult.

“I avoided him, but I tried to be discreet because if people saw that there was a strange relationship between us, they would’ve never believed me,” he said.

Paola Ruiz took to social media to call out her former partner and the father of her daughter after she says he physically attacked her during her pregnancy and after the birth. Frustrated by his bouts of jealousy and control issues, Ruiz told him she was leaving with their then three-month-old daughter, she said. He reacted by pushing her to the floor and hitting her while she protected the baby with her body, she recalled

“I started calling for the police, screaming at the top of my lungs for help,” she said. After eight hours of on and off fighting, a group of six female neighbors knocked on the door and confronted the man when they saw her beat up and with a swollen face, she recounted.

She filed a complaint with police, but said she was told that cases like hers can take years to resolve.

“I felt frustrated and sad. I then knew nothing would happen,” she said.

She filed a report anyhow in August 2020, but said there have been no developments. She said that because no one directly witnessed the aggression, police said her case would not proceed.

After she published a Twitter thread accusing her abuser, Ruiz said other women have come forward with their own stories of abuse and assault with the same man.

In response to the recent accusations, chief prosecutor Tarek William Saab announced in late April that he was opening investigations into McKey, Ogando and José Arceo, another theater director, among others. He said prosecutors have filed 8,450 charges for sex abuse crimes since 2017 and that his office is proposing a “revision” to Venezuelan law to ensure aggressors don’t escape justice due to “gray areas” in the law.

Organizations like Yo Te Creo and survivors such as Cardone Fulop, who now considers herself an activist, say that they believe their cause will continue to gather momentum.

“This has started and I will not stop,” she said. “I won’t stop because I want a world that’s free of violence.”