Venezuelan insurgent describes how betrayal in ranks produced failure, summary executions

More than four dozen men who set out in motorboats on the first day of May from Colombia as part of a botched coup known as Operation Gideon, a doomed attempt at ousting Venezuelan strongman Nicolás Maduro, were betrayed by five companions who sold the exact landing coordinates shortly before departure, says a high-ranking insurgent.

In an exclusive interview, the man involved in Gideon broke his silence to detail events that led to the capture of 47 Venezuelans and two Americans, and the execution of six Gideon participants.

The Maduro regime knew precisely where the first boat would arrive and soldiers were waiting for the would-be liberators as they attempted their landing, said the man who goes by the nom de guerre Cacique, noting the mission had been compromised.

An article published by The Associated Press hours before the launch had warned the world of an impending coup attempt by former soldiers from the Venezuelan military, trained by associates of former Green Beret Jordan Goudreau and his company, Silvercorp USA.

The invaders, a rag-tag collection of deserters and political opponents of Maduro, still believed they could succeed. They trusted that the regime didn’t know exactly where in Venezuela they would enter and when, and they were convinced that Venezuelans would rise up in support, Goudreau and Cacique both said.

The broader insurgency effort is believed to have been infiltrated much earlier, but the plotters’ bet was that the regime didn’t know the key details, and they had the confidence of Gideon’s leaders.

“Forty-eight hours earlier, the operation was sold,” according to Cacique, a Venezuelan rebel officer who operated the communications center for the failed incursion from an undisclosed city in the United States. “There is a traitor … who sold the operation two or three days before and who was leading a group of five, who were wrapped up in collecting a reward for tipping to the invaders’ arrival.”

In his first interview since the tragic events in May, Cacique, a Spanish nickname given to a local boss, said the turncoats hoped to receive a reward for the capture of Robert Colina, whose alias was Pantera, Spanish for panther.

Colina led the Gideon advance team, and had been a captain in the National Guard, the military component in Venezuela charged with domestic security.

The identities of the other 10 rebels on the boat with Pantera were unknown by the regime. Pantera was the prize sought by Maduro and offered by the turncoats.

The invaders were intercepted in the overnight hours when they reached the Venezuelan coastline on May 3 near the town of Macuto, just north of Caracas. It did not end well.

The names of the betrayers are a secret carefully guarded by Cacique and the group called Caribe, a loose grouping of about 3,000 Venezuelan military personnel who have deserted the regime’s ranks and from abroad are trying to coordinate to overthrow Maduro.

The day will come to settle scores with the turncoats for their actions, Cacique vowed in the interview.

The official regime version of events, from Venezuelan Information Minister Jorge Rodriguez, is that there was a firefight after Pantera and colleagues began firing on agents who were waiting for them when they touched land.

Opposition lawmaker Wilmer Azuaje investigated the events for a human rights violation case introduced to the International Criminal Court in the Hague. He argues the 11 men were captured alive, but six, including Pantera, were executed by regime forces.

“They captured all of them alive and then to fabricate a ‘false positive’ [a fictitious confrontation], they massacred all those people,” the opposition lawmaker told the Miami Herald and McClatchy on Monday. “They were captured. They were disarmed. They were tortured, and then they were taken to the site, and shot to simulate a confrontation” that never took place.

Azuaje makes the claims based on the forensic reports written by the regime’s own National Investigative Police, which point to inconsistencies in Maduro’s version of the events. For example, the autopsy reports show that some of the victims had friction burns in their buttocks caused possibly by being dragged naked on the sand while they were still alive. Most of the victims had execution-style wounds, some of which were inflicted with two quick shots at very close range, leaving traces of gunpowder on the bodies.

The report, submitted by Azuaje as evidence to the international court on Oct. 13, said the bodies show still other signs of torture such as hard blows and strangulation.

Evidence also suggests that some of the invaders were executed at one site and placed hours later at another location, he said, noting the coagulated blood did not correspond to the position in which the bodies were later found. Additionally, photos don’t show weapons near the bodies, he said.

And another indication of a staged firefight, according to Azuaje, comes from photos of the boat used by the invaders. The small vessel shows numerous bullet holes, some of them below the waterline, yet none of the bullets struck gasoline-filled barrels on board.

Pantera was among the dead in Macuto and was one of the three people hired to pilot the first, advancing boat, said Cacique, who said he served as a link between Caribe and the men who participated in Operation Gideon.

The five survivors from the first vessel are among the 47 would-be invaders that the regime now has behind bars. They are said to be under special watch and moved from time to time.

“These people, of course, have them under extreme security measures because they are the only witnesses to the execution of those guys,” Cacique said.

Filling in Blanks

The events described by Cacique, who is in hiding in the United States, are a puzzle piece in a story whose details are only now beginning to fit together.

Two American associates of Goudreau, former special operations soldiers Luke Denman and Airan Berry, were captured and hastily sentenced in Venezuela to 20-year prison terms. Former New Mexico Gov. Bill Richardson has been working on behalf of their families to seek their freedom.

The two Americans were aboard a larger second vessel that carried the bulk of the invading force. The turncoats were believed to be on the second vessel carrying the Americans and 46 people in all.

Cacique and others believe the regime was unaware of this second boat during the May 3 incursion, because naval patrols did not immediately go out looking for it. It was found late in the afternoon about an hour from Macuto, adrift at sea and idling as it was almost out of fuel.

“Pantera was killed on Sunday at 3:30 in the morning. It was many hours later, in the afternoon of that same day, that there was information about the other boat,” said Cacique, who added it had lagged behind after stopping in the state of Falcón state to avoid a naval frigate.

When the men returned to sea from Falcón, they lost one of the two large engines. They were forced to run the remaining one at full throttle to push the heavily loaded vessel in an attempt to compensate for the engine loss.

That quickly depleted fuel reserves, Cacique said. By the time they were chased by regime forces, their boat was virtually dead at sea, the remaining engine barely running. The only photo from the 40-hour passage shows Berry and Denman on the boat.

“They ran out of gas, and had no choice but to get closer to shore. By that time, they were looking at the shoreline and they knew they were being watched. There was movement of vehicles from the coast. You could see the road. They looked for a less dangerous place to approach and saw this village of civilians. By that time, helicopters were already coming behind,” Cacique said.

Upon landing, the men separated and tried to flee but most were captured that same day. Others were captured in the following days as the regime forces hunted them down.

Of the 50 men who left La Guajira, a coastal city in Colombia, only four managed to escape into the mountains and evade search operations.

Telling the Story

Goudreau broke a months-long silence in an investigative report published on Oct. 30 by the Miami Herald, el Nuevo Herald and their parent company McClatchy, all of whom were given the entire contents of his phone, showing texts, emails, chats, photos and videos.

The contents show the frantic communication from men in the field back to Goudreau, confirming the chaotic events described by Cacique.

At 2:23 p.m. on May 3, a man identifying himself as Antonio wrote Goudreau asking if Pantera was dead.

“It is not confirmed; be ready hermano,” he responded. “We are engaging the enemy in Caracas.”

Around 20 minutes later, Goudreau sent another message: “Attack any of your objectives.”

By the next day, text and voicemail messages started pouring in to Goudreau — some from Venezuelan well-wishers, some from people who wanted to join up and still others from journalists.

The phone logs show Goudreau frantically trying to get Denman and Berry out safely.

At 5.40 a.m. on May 4 he wrote a friend that the “pilot boat was hit bad” but the “majority of the force made landfall.”

“The boys [Denman and Berry] are alive,” he wrote around two hours later to the same friend. “Escape and evading in Venezuela.”

The only communication between Cacique and Goudreau on the phone dates to 3:30 p.m. on May 4.

“I need the last name of Luke and Aaron,” Cacique wrote, misspelling Berry’s first name.

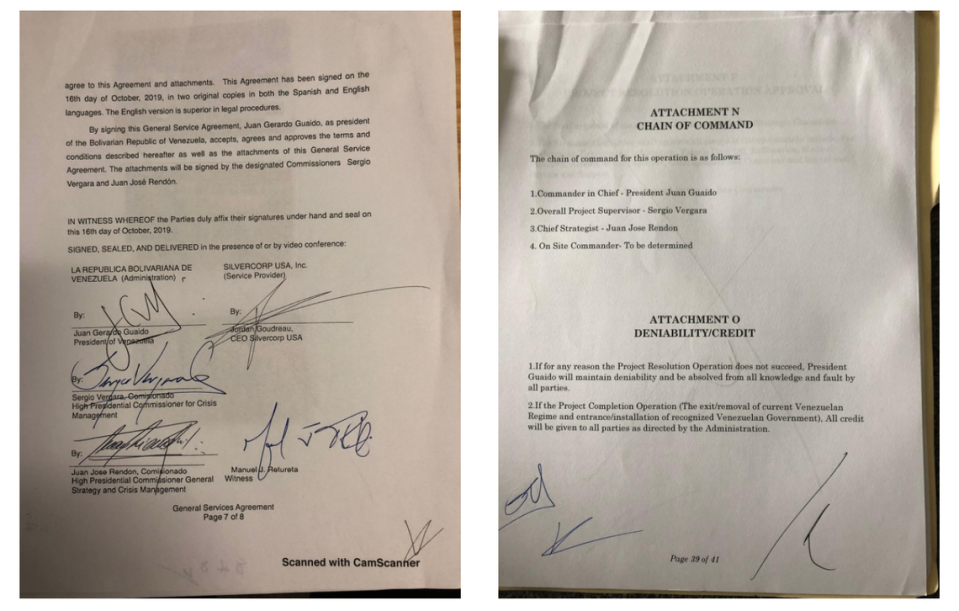

In a lawsuit filed in South Florida on Oct. 30, Goudreau identified Trump administration officials Andrew “Drew” Horn and Jason Beardsley, who he alleged were aware of his plans to topple the Venezuelan government and encouraged him. These officials declined to comment, as did the State Department.

A former U.S. special operations fighter awarded three Bronze Stars for valor, Goudreau also identified participation by former Trump bodyguard Keith Schiller. Through an associate, Schiller acknowledged bringing Goudreau to a single meeting about humanitarian aid to Venezuela but denied any additional relationship with him or helping in a coup effort.

The story behind the botched coup is full of intrigue, with Goudreau claiming to have held meetings at the Trump Doral golf resort in South Florida and at the Trump hotel blocks from the White House. Another source described meetings at dusk on the 12th fairway of the Red Course of Trump Doral in the back of rolling limousines and in restaurants.

Weeks after everything went awry on the Venezuelan coastline, agents from the Tampa office of the FBI raided a Boca Raton apartment on May 21 where Goudreau was visiting and seized nearly $57,000 in cash. Multiple people with knowledge of events said a federal investigation was ongoing.

Miami attorney Gustavo J. Garcia-Montes brought the $1.4 million breach of contract lawsuit on behalf of Goudreau against Juan Jose Rendon and others who he said purported to represent Juan Guaidó, the Venezuelan lawmaker the Trump administration recognizes as the legitimate president of Venezuela

Weeks after the report, the lawyer shared a Nov. 6 letter from the FBI noting that the Justice Department “declined to file a civil forfeiture complaint” and that Goudreau’s money would be returned.

The FBI “does not comment upon the existence nor the nonexistence of any investigation,” the agency said in a statement to the Herald and McClatchy.

Still, the letter appeared to send a signal about prosecution.

“They are not moving forward, or they are moving forward very slowly on the investigation and have not been able to get to a moment where they can indict,” Garcia-Montes said.

“Because, had they come out with an indictment, they would probably have assigned the funds to a criminal case. And they were coming up on a deadline on the administrative forfeiture case.”