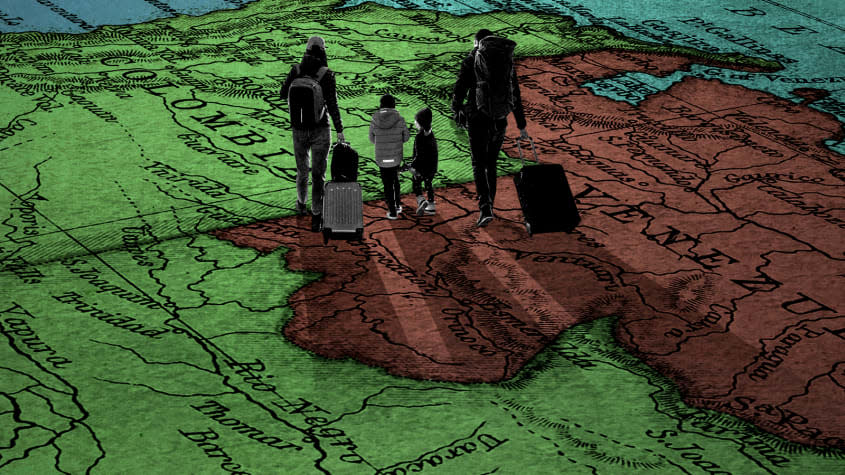

The Venezuelan migrant crisis and the U.S. response, explained

Venezuelans are continuing to flee their country due to economic and political instability, a lack of food and medicine, and enduring violence. The U.N. Refugee Agency estimates there to be at least 6.8 million Venezuelan refugees and migrants worldwide, making it the world's second-largest external displacement crisis. Here's everything you need to know:

What countries have seen an influx of Venezuelan migrants?

Most migrants have been settling in other countries inside South America, but many are crossing the Darién Gap — a dense jungle linking Panama with Colombia, and one of the world's most dangerous migration routes — in order to reach the United States. On Monday, Panama's National Migration Service said a record 151,582 migrants crossed into the country between January and September; most were Venezuelans, and more than 21,000 were minors. At least 18 migrants are known to have died this year while crossing the Darién Gap.

What happens when the migrants arrive at the U.S. southern border?

Relations between the United States and Venezuela are fraught — the U.S. does not recognize Nicolás Maduro as the legitimate president of Venezuela, and Maduro's government often refuses to allow deportation flights from the U.S. and Mexico to land in his country. Because of this, most Venezuelan migrants who arrive at the southern border are screened and then released with permission to remain in the U.S. on a temporary basis while going through deportation proceedings. During this time, they are monitored and can apply for asylum.

Between October 2021 and August 2022, more than 150,000 Venezuelans were apprehended at the southern border, and Customs and Border Protection data shows that, within the last few weeks, about 1,000 Venezuelans cross the border daily. In comparison, almost 48,000 Venezuelans were apprehended at the southern border in the 2021 fiscal year, Reuters reports.

How is the U.S. trying to deter Venezuelans from illegally crossing the southern border?

On Wednesday, the Biden administration announced it is launching a humanitarian parole program for up to 24,000 Venezuelans. To be eligible, migrants must have a sponsor who is already in the U.S. and able to provide financial support for up to two years. Those selected for the program will be temporarily able to work legally in the United States. The program is not open to migrants who enter Panama or Mexico illegally.

At the same time, effective immediately, "Venezuelans who enter the United States between ports of entry, without authorization, will be returned to Mexico," the Department of Homeland Security said in a statement, citing the Title 42 public health authority. "These actions make clear that there is a lawful and orderly way for Venezuelans to enter the United States, and lawful entry is the only way," Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas said in a statement.

Where are the migrants settling in the United States?

Many are remaining in the border states where they crossed, or heading to northern areas to connect with family or friends. In the last few months, the Republican governors of Texas and Arizona have sent migrants to northern cities, including New York City, where Mayor Eric Adams has declared a state of emergency. More than 17,000 asylum-seekers from South and Central America recently arrived in the city, straining its resources. New York City is required under a 1980s legal settlement to provide housing for anyone who needs it, Bloomberg reports, and the GOP officials sending migrants to New York have "manufactured" a crisis, Adams said.

Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis (R) also used state funds to pay for two planes to take migrants from San Antonio, Texas to Martha's Vineyard in Massachusetts; the Treasury Department's inspector general said there will be an investigation into whether DeSantis used funds meant for coronavirus aid to transport the migrants.

Doral, Florida, is a popular destination for many of the migrants, as 35 percent of the city's population was born in Venezuela, The New York Times reports. Most of the migrants arrive with no money and hardly any personal belongings, and there are organizations in the city ready to help those in need, including "Raíces Venezolanas," or Venezuelan Roots. The group has storage units filled to the brim with food, clothes, sheets, towels, pots and pans, toys, car seats, and strollers. "The mission of this is to be ready to help Venezuelans who are arriving and don't have money," founder Patricia Andrade told the Times. "We try to have the minimum things to have quality of life."

You may also like

5 cartoons about Alex Jones' billion-dollar penalty

Holiday season airfare could be among most expensive ever, report says