‘Very evil.’ Trans teen from SC was lured from home, murdered on first date

On June 30, 18-year-old Jacob Williamson was supposed to go to Carowinds on his first ever date. He’d never been to the amusement park, but in the last month Williamson had done a lot of things for the first time.

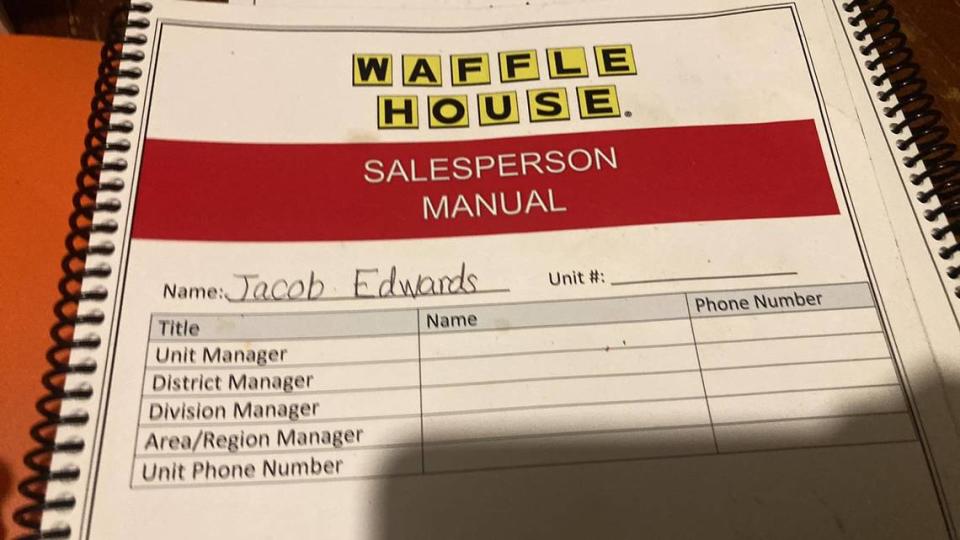

He had moved out of his parents’ house, started a job at a Waffle House and became more comfortable in his identity as a publicly out, trans man in the conservative small town of Laurens, S.C.

Williamson had also met a man online and they talked incessantly. He offered sympathy and support to Williamson, who had left home with only the clothes he had on him and was sleeping on a couch belonging to a family friend, Promise Edwards.

When the man found out that Williamson had never been to the amusement park, which straddles the North and South Carolina border, he said he’d drive them to the park for a date, according to Edwards.

“I told Jacob I’m not really comfortable with you going,” Edwards said.

Her worst fears were realized when Williamson disappeared the night the man picked him up for a date.

On July 4, Williamson’s body was found on the side of a road in Pageland, South Carolina, roughly eight miles from Monroe, N.C., where Edwards and police say 25-year-old Joshua Newton lived. Less than two days later, deputies from the Union County, N.C., Sheriff’s Department arrested Newton and his girlfriend, 22-year-old Victoria Smith, in Williamson’s death. Newton has been charged with first degree murder and obstruction of justice.

Law enforcement officials have said that the case is not being investigated as a hate crime.

“This just appears to be a very evil individual or individuals that took the life of (Williamson),” said Lt. James Maye, a Union County Sheriff’s Department spokesperson.

The story of Williamson’s life and death has taken on a life of its own nationally, with #JusticeforJacob trending on TikTok and coverage from national news outlets including CNN.

But in South Carolina, where lawmakers have introduced bills to ban gender affirming care, Williamson’s death is a grim reminder of the precarious and often marginalized lives of LGBTQ+ teens. Many of them are forced to navigate the world with little to no support from their families or communities that might have ostracized them.

“When someone is rejected by family, by church, by community, there is a desire to seek out love and acceptance — we all have that innately within us. What is really scary when you think about transgender young people is that the quest for love and acceptance can put them in danger,” said Jace Woodrum, the executive director of the ACLU in South Carolina.

Nationwide, the impact of marginalization can be seen in sobering statistics: Roughly 40% of teens experiencing homelessness identify as LGBTQ+, according to the National Network for Youth. One 2015 survey found that more than half of transgender and non-binary respondents experienced intimate partner violence in their lives.

“He was a loving, caring soul that only wanted to be loved and accepted by everyone,” Edwards said.

Who was Jacob Williamson?

When Williamson arrived at Edward’s home at the end of May, he had nothing but the clothes on his back, Edwards said.

“He called me and he just asked me, ‘Hey can I come and stay with you? Please, I don’t have anywhere to go,’” Edwards said.

In the month that followed, Edwards said that she helped Williamson get a job at the Waffle House where she worked. In his employee paperwork he filled out his name as “Jacob.” He’d taken the name from a popular character in the Twilight Saga and it represented a happy time in his life, Edwards said.

When reached, Williamson’s mother, Brittney Patterson-Shealy, said she did not believe Williamson was transitioning and said she only knew her child by one name.

When speaking with reporters, Patterson-Shealy exclusively referred to Williamson with feminine pronouns. She said it was Williamson’s decision to leave home.

“She was 18 and done what she wants,” Patterson-Shealy said.

But at 18, Williamson often seemed much younger. Both Edwards and Patterson-Shealy described him as having the mind of a 14-year-old.

He was the type of person who would get in a mud puddle with 5- and 6-year-olds rather than sit on the porch and have conversations with adults, Edwards said.

Williamson was Patterson-Shealy’s first-born child and ”helped me learn to be a mom,” Patterson-Shealy said. “We both grew up together.”

Williamson was “ innocent,” said Patterson-Shealy, but that also made him “real gullible.”

Willamson slept with a stuffed miniature owl every night, was an “anime fanatic,” loved to draw, was an avid gamer, and would belt out Christmas carols in the dead of summer, Edwards said.

With one of his first paychecks, Williamson bought headphones, a fidget spinner and his first ever chest binder online. Edwards remembered that he spoke about it daily, ecstatic about when it would arrive. The package was delivered three days after his body was found.

“He never met a stranger, and if he did, you wouldn’t be a stranger for long,” Edwards said. “He was gonna make you laugh. He was gonna make you talk to him. He was gonna get your attention.”

One of Edwards’ fondest memories of Williamson is from right before he died, she said.

She was using the restroom in her house, watching TikTok, when she saw a snake.

“I just ran out of the bathroom, I didn’t even pull my pants up, screaming ‘it’s a snake, it’s a snake!’ and Jacob jumped up off the couch going ‘Where? Where?’” Edwards said.

He ran into the bathroom to find the snake for her and spent an hour searching for it. He was determined to keep it as a pet, she said. He named it Mr. Slithers and told Edwards he was convinced if he formed a bond with it, it would come to him.

What happened?

The spiral of exclusion and marginalization that often begins when transgender teenagers feel that their identity is rejected by their family often leads them on a search for acceptance and validation elsewhere, said Chase Glenn, the former head of LGBTQ+ Health Services at MUSC Charleston and current executive director for the Alliance for Full Acceptance.

“It’s our human nature, we’re going to seek that out,” Glenn said.

Williamson seemed to find that in Newton. The two began talking before Williamson left home, according to Patterson-Shealy, who said that she and Williamson’s stepfather tried to put a stop to the relationship. The two had met online, according to investigators.

Edwards said the relationship developed over their phones, through text messages and apps like Snapchat, Discord and Twitch. They played video games together and talked about the rejection they had both faced.

After moving in with Edwards, Williamson resumed contact with Newton and the two spent up to ten hours a day on video calls, Edwards said.

In late June, after Williamson had been living with Edwards for three weeks, he said that he wanted to meet Newton in-person, go on a date to Carowinds, and stay with him overnight in North Carolina.

When Williamson insisted on visiting Newton, Edwards said she spoke with a woman who claimed to be Newton’s mother who said that she would be right next door the entire time Williamson stayed with Newton, Edwards said.

At the time, this gave Edwards a sense of security. Now, she wonders if it was Smith on the phone with her.

Smith, who has been charged with obstruction of justice and accessory after the fact, is featured prominently on Newton’s social media accounts. The couple had been dating since June 2022 and started living together less than a month later, according to Facebook posts.

They live-streamed video games and posted about each other on Facebook and TikTok accounts, where Smith adopted the handle “HisMaster_” and Newton used “Her.demon.”

They paired these gothic personas with heavily edited profile pictures (Smith described herself on Facebook as a graphic designer) featuring flames, skulls and glowing eyes.

Edwards knew none of this before Williamson left, but she still had her concerns. “You don’t just go with people you don’t know, overnight, that’s not safe,” Edwards remembered telling Williamson.

“I asked Jacob the obvious question: why would a straight man want to pick up a transgender female to male if he’s straight,” Edwards said. “That’s a red flag for me as well. And I try to be respectful of the community but that I didn’t understand.”

Williamson assured her it was fine and said Newton is pansexual, telling Edwards: “It’s very sweet, he’s been through a lot of the things I’ve been through.”

“He felt like they were kindred spirits,” Edwards said.

Before he left, Williamson downloaded Life360 — an app that allows family members to track one-another — onto his and Edwards’ phones. This app ultimately helped police locate Williamson’s body, Edwards said.

On June 30, when Newton arrived in a green Saturn at the Waffle House to pick up Williamson, Edwards said she had her 19-year-old daughter make Newton stand in front of one of the restaurant’s new cameras.

That night Edwards called Williamson to check on him. It was nearly 11:30 p.m., and Williamson sounded annoyed, she said.

She asked him where they were, and Williamson said Newton was showing him the woods behind Newton’s house. “I said red flag, red flag,” Edwards remembered, and took a screenshot of his location.

At 12:13 a.m. Williamson’s phone went offline. She never heard from him again.

Remembering Jacob

Starting the next day, Edwards searched desperately for Williamson, she said. She filed missing persons reports and for three days she didn’t sleep or brush her teeth.

Law enforcement officers interviewed Newton twice at the trailer on Bethphage Lane in Monroe, North Carolina. In one video shared to social media, it appears that Newton live-streamed part of one of these conversations.

Edwards said she and Williamson’s father stayed overnight in their cars in a Walmart parking lot in Monroe so they could search for him as long as possible without making the trek back to Laurens. She put out pleas on social media for help in the search and with gas money.

“It was tragic for everybody,” Patterson-Shealy said, saying that Williamson was taken too soon but that she drew comfort from the knowledge that Williamson was now in heaven.

Both Edwards and Patterson-Shealy agreed with law enforcement that they didn’t believe Williamson’s death was a hate crime. But without a clear motive, those who loved Williamson are left wondering why he was killed.

“The only reason my child got in the car with that man is that he promised to take (Williamson) to Carowinds,” Patterson-Shealy said.

Along with several LGBTQ+ organizations, Edwards is arranging a vigil in Williamson’s memory with help from city officials and the community of Laurens. The town, with just more than 9,000 residents, traces its history to the mid-1700s and was named after a prominent slave trader. For years, it was home to The Redneck Shop, which called itself the “world’s only Klan museum.” The shop closed in 2012 after a Black pastor won a lawsuit proving he owned the building.

The vigil is scheduled for Monday at 6:30 p.m. at The Ridge at Laurens, a local community center. Attendees are asked to wear purple, according to PFLAG in Spartanburg, which is helping to organize the vigil along with the Alliance for Full Acceptance and the Uplift Outreach Center in Spartanburg. Purple often symbolizes support for LGBTQ+ youth.

“Jacob was a vibrant young soul who touched the lives of many and left us far too soon,” PFLAG of Spartanburg said in a statement. “We stand together as a community, devastated by the loss of this young man. Jacob’s life was tragically cut short, reminding us of the urgent need for acceptance, understanding, and equality for all.”

“Jacob is getting the amount of love and support in his death that he deserved in his life,” Edwards said.