Veterans Voice: As we celebrate Victory Day today, here's what it means to me

Today, Rhode Islanders observe the holiday known as Victory Day.

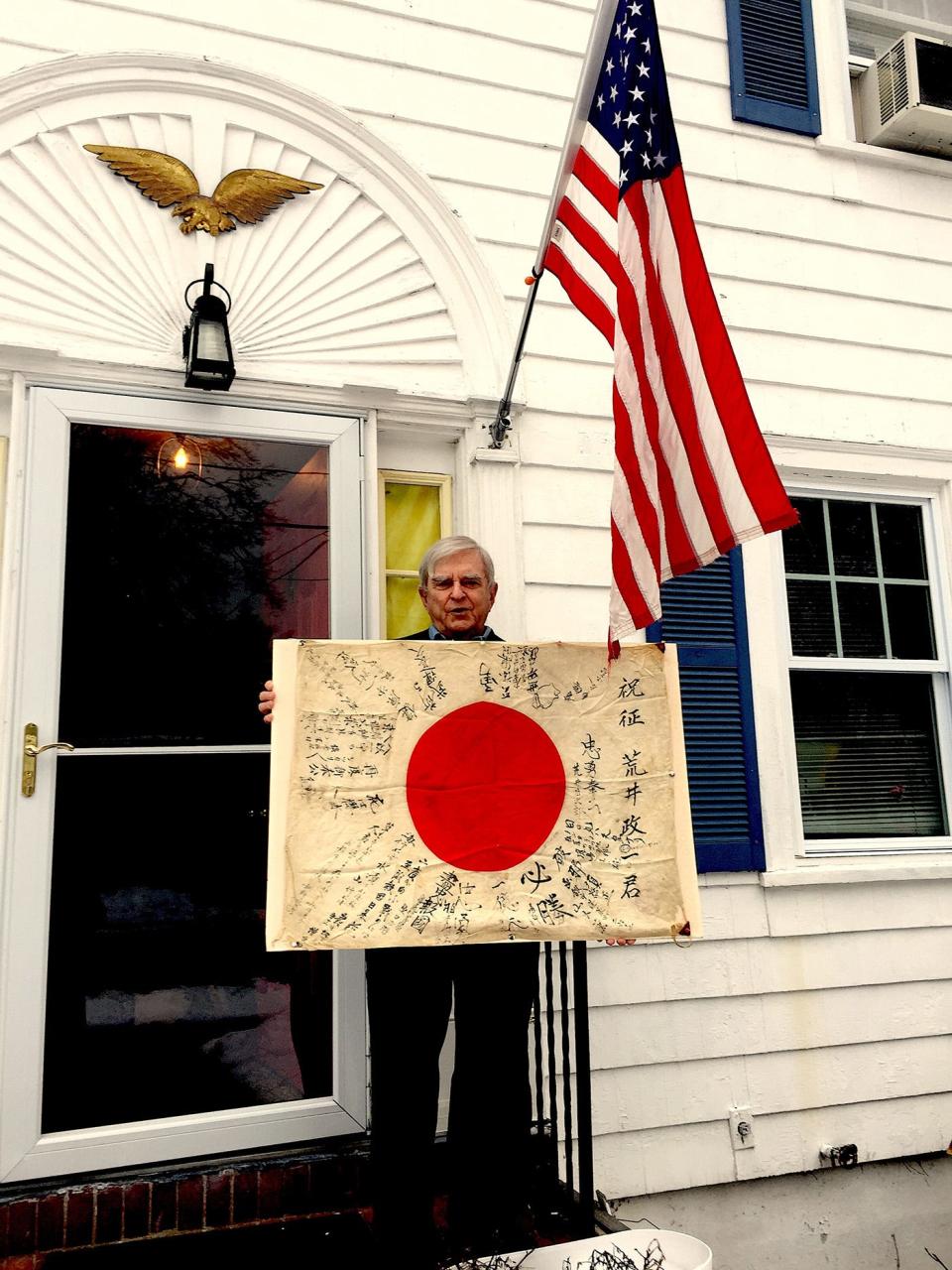

I will spend a few minutes contemplating a World War II Japanese flag, collected on some forgotten Pacific island and brought home by an American GI as a war souvenir. The aging flag features the famous Rising Sun in the center, surrounded by calligraphy radiating out from the red center like a sun’s rays.

This flag is now the focus of a personal quest.

On Aug. 14, 1945, President Harry S. Truman announced the unconditional surrender of Japan.

RI establishes Victory Day as a state holiday in 1948

A year later, Truman declared Aug. 14 as Victory Day, although it was never designated a national holiday. In 1948, Rhode Island lawmakers established Victory Day as a state holiday.

Contrary to popular belief, the official name has always been Victory Day, not “Victory over Japan Day” or “V-J Day” — even though most locals have referred to it that way for generations.

Every few years, there’s talk of eliminating the observance, or at least changing its name. Some consider it to be racially insensitive, because it singles out Japan, now a staunch ally.

They have a point. When the war ended in Europe, that celebration was called V-E Day, for Victory in Europe — not V-G Day, for Victory over Germany.

Why continue to single out Japan? Why promote needless anti-Asian sentiment and make Asians, especially the Japanese, the enemy again, even if it is only for one day?

As Victory Day approached this year, my own internal battle with this question resurfaced.

Veterans Voice: Celebrating new benefits for military pensioners

My Japanese connection

I worked for 20 years to bring a retired aircraft carrier into Narragansett Bay as a world-class family attraction and education center. That effort focused initially on the USS Saratoga.

The name “Saratoga” commemorated the American Revolutionary War victory at Saratoga, New York, in 1777. The third U.S. Navy warship named Saratoga was launched in 1842 and was part of Commodore Matthew Perry’s famous “Black Ships” squadron during his missions in 1853 and 1854 to open relationships between the United States and Japan.

Recognizing this significant connection, we linked up with the Japan America Society and began participating in activities involving the two countries. I joined the advisory board of JAS and was a member of the Newport delegation to Japan for the 2007 Black Ships festival in Shimoda.

Meanwhile, we collected artifacts for museum displays. While developing a World War II exhibit in 2006, I acquired the signed Japanese flag that is the subject of this story.

The flag, presented by the auction house as signed by war criminals, went into storage and was not translated for almost 14 years.

Although our aircraft carrier dreams came to naught, we developed a backup plan. To ensure a location for all the artifacts collected over the years, as well as to provide a permanent home for the Rhode Island Aviation Hall of Fame, we began to develop a land-based facility at Quonset.

Just as this Hall of Fame project began to gain momentum, the coronavirus hit in 2020, closing off our normal fundraising activities. We decided to sell assets to generate operating capital.

One asset we decided to sell was the Japanese flag. The flag is not what it seemed. To sell it, however, we needed to find out exactly what it was.

The flag, measuring 34 inches by 26 inches, was described as an "Imperial flag signed in Japanese by at least 20 men under indictment for war crimes.” The auction house did add the caveat, “This example, however, is lacking a firm provenance and is yet to be translated.”

I reached out to William R. Farrell, chairman of the National Association of Japan-America Societies. Farrell had also taught Japanese history at the U.S. Naval War College in Newport.

I was also introduced to Capt. Yukiko Bito, liaison officer for the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force and military professor, International Programs at the War College.

Bito explained that this was a “good luck” flag, called “Yosegaki Hinomaru,” given to a Japanese soldier by his family and friends as he went to war.

It was not signed by war criminals.

Farrell concurred, saying that such flags always contain uplifting messages such as "Congratulations on your expedition,"Be victorious" and "Serve honorably."

Bito explained that these flags usually were carried into battle by the recipient, because they were filled with the best wishes of his loved ones, hoping and praying for his safe return.

“Being Japanese," she wrote, "I can’t look at this flag without tears coming to my eyes as I pray for him and his family.”

Clearly, this flag was no longer an impersonal asset that the museum could sell. This was not a battle flag, designed to inspire men to fight to their deaths in fanatical banzai charges. It was a talisman from a soldier’s family, hoping to keep him alive.

Our mission changed — with the help of Bito and others, we set about to find this soldier’s family.

Veterans Voice: Navy vet left his mark as a philanthropist

She published the story in the Japan America Navy Friendship Association newsletter. In February 2021, I heard from Yutaka Mitsuo of the Yomiuri Shimbun, the largest daily newspaper in Japan: “I was impressed by the writing about the Japanese flag … by CAPT Bito in the JANAFA bulletin.

“We, the Yomiuri Shimbun, might be able to help return the soldier’s flag to his family by writing a story.”

This was great news! The largest newspaper in Japan? Surely someone would see this and respond.

Mitsuo began researching the flag’s history, searching for clues in the notations marked on the flag. The soldier’s name was Seiichi Arai, and there was reference to the city of Hokedate on the island of Hokkaido.

He reached out to the Japan War-Bereaved Families Association, and also asked for help from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare. To his surprise, the search came up empty. That name did not appear on the official list of war dead, and no Seiichi Arai seemed to have lived in Hokkaido.

The feature appeared in June 2021. It showed a picture of the flag and asked that anyone with further information come forward.

To date, no one has.

The Obon Society

Keiko and Rex Ziak began their mission in 2009. Their inspiration came after the Good Luck Flag of Keiko’s grandfather, lost in the jungles of Burma, was returned to her family.

A Canadian visiting Japan left it at his hotel, hoping it might be traced. It took the hotel a year to find Keiko’s family. Seeing the reaction of her grandmother and other family members, Keiko and her husband began to research these Yosegaki Hinomaru. They learned there are thousands of them out there — perhaps as many as 50,000 in the United States alone.

The Ziaks created the nonprofit Obon Society, based in Astoria, Oregon, to assist others who wanted to return personal items taken as war souvenirs. They took their name from the Obon festival, commemorating deceased ancestors.

Over the years, Obon has grown into an international organization. They receive items from all over the world.

The Obon group has returned some 470 heirlooms — mostly Good Luck Flags — to families in Japan. More than 400 other items — “nonbiological remains,” as Keiko Ziak calls them — are pending identification and family location.

“Our team consists of 14 specialists, spread out across five states and five prefectures in Japan,” Ziak wrote in an email.

The Ziaks believe Yosegaki Hinomaru are more than just possessions lost on the battlefield.

Keiko Ziak makes the impassioned argument that these flags have just as much significance to Japanese families as do bodily remains of military personnel missing in action that are returned to American families.

Ziak emailed that Obon conducted a detailed study of the reactions of American families who received the biological remains of their missing relatives. “We discovered they matched exactly what the Japanese say and feel when they receive a Yosegaki Hinomaru, or other personal [heirloom].”

Whether the return is part of the soldier’s biological remains or a Yosegaki Hinomaru, the item “provides the same relief, closure, joy and sense of completeness.”

Turning point for me

The military memorabilia market is booming, with buyers and sellers engaged in a brisk commerce of relics found on battlefields or among the possessions of deceased soldiers.

Native American arrowheads, Civil War buttons, German pistols, uniform badges — all are of interest to collectors. Items bearing bloodstains or bulletholes are prized. But how often do we reflect on how these items were obtained?

Yes, “to the victors belong the spoils” has been the expression for many years.

After reflection about these flags, however, my opinion has changed. These flags were usually folded up and carried in a Japanese soldier’s pocket, much as a GI might carry a treasured letter from a loved one.

Obon Society is kept busy not because they solicit the return of these items, but because more and more American veterans and their families want them returned.

We have not availed ourselves yet of the services of the Obon Society only because one of their conditions is that no flags are returned to donors, even if families in Japan cannot be found.

While our first priority is to locate Seiichi Arai’s family and return this flag to him, our fallback position would be to use it as the centerpiece of a “V-J Day” educational exhibit at our new facility in Quonset. We hope to help eliminate the anti-Japanese (and perhaps anti-Asian) basis associated with this holiday, and we believe such an exhibit could help achieve that goal.

Veterans Voice: Keeping alive the memory of troop ship Dorchester's RI victims

Events

Aug. 14, 11 a.m.-3 p.m., “World War II Sunday Funday” at Whitin Mill in Northbridge, Mass. Sponsored by the National Park Service (Blackstone River Valley National Historical Park), this free event will include military and manufacturing exhibits from Woonsocket's Museum of Work and Culture and Battleship Cove in Fall River. Attendees will get to meet World War II veterans and hear their stories. There will also be special activities for children. All veterans and serving military personnel will receive Federal Recreational Land passes, which provide free access for veterans and guests to national parks and historic sites nationwide. The address for the Whitin Mill Complex is 50 Douglas Rd., Whitinsville, Mass. 01588; phone is (508) 234-6232. From Providence, go north on Route 146 about 30 miles to Exit 8.

Aug. 15, 6-7:30 p.m.: U.S. Rep. David Cicilline will host his annual Veterans Community Conversation at Slater Park Pavilion, 825 Armistice Blvd., Pawtucket 02861. The event, postponed from July 25, will feature a barbecue dinner for veterans, active service members and their families.

Aug. 27: The sixth annual Coventry-West Greenwich Elks Veterans Fundraiser Golf Tournament will have an 8 a.m. shotgun start at Coventry Pines Golf Course at 1065 Harkney Hill Rd. in Coventry. Nine holes with cart is $75 per person for this scramble tournament. The event will feature various prizes and raffles and a gift bag for each player. A steak fry is scheduled for after the tournament at the Elks Club at 42 Nooseneck Hill Rd. in West Greenwich. Payment must be made by Aug. 19. Make checks payable to: BPOE #2285, and mail to Lori Ashness, 111 Tomahawk Trail, Cranston, RI 02921. For more details, call (401) 573-5063, or email ashnessla@gmail.com.

Aug. 29 to Sept. 2: “Learn to Weld Training Program” at The Steel Yard, 27 Sims Ave., Providence 02909. Attendees will learn foundational welding through an artistic curriculum. Participants will receive a $250 stipend and a certificate of completion. To apply, email workforce@thesteelyard.org, call (401) 273-7101 or visit https:// www.thesteelyard.org/job-training.

Sept. 15, 4:30-7:30 p.m.: Learn to Surf Cast for Free at Scarborough Beach. The Providence Vet Center is teaming up with the Narragansett Surf Casters to offer a class to 15 service members and veterans. All the equipment you need to learn to catch fish from shore, along with instruction, will be provided by members of the Surf Casters. Sign up with Justyn Charon at (401) 739-0167 or email Justyn.Charon@va.gov.

Sept. 17, 9 a.m.-2 p.m.: Rhode Island National Guard Resource Fair, Camp Fogarty, East Greenwich. Resources and connections will be offered to help service members and families.

To report the outcome of a previous activity, or to add a future event to our calendar, please email the details (including a contact name and phone number/email address) to veteranscolumn@projo.com.

This article originally appeared on The Providence Journal: Japanese flag carries historic secret that Frank Lennon found out