Veterans Voice: Service dog a good soldier to Vietnam vet

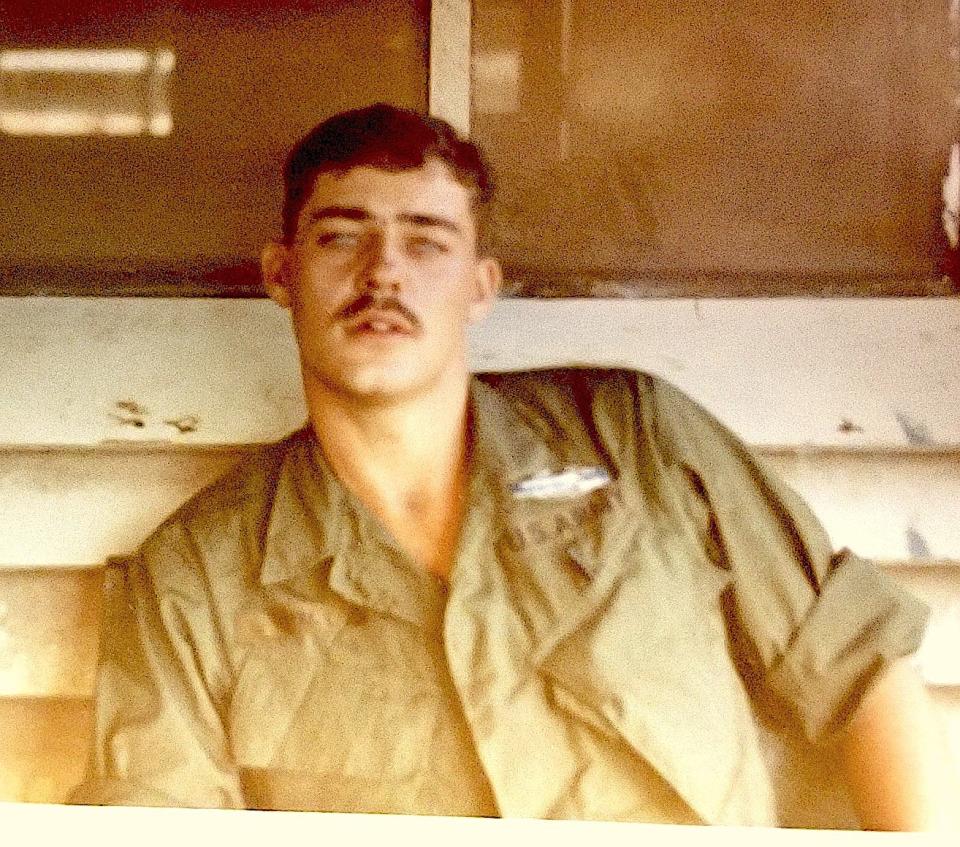

Ken Howe, 74, grew up on Providence’s East Side. His companion Fiona, 7, was born in Minnesota and grew up in North Dakota. This is the story of how they met, and how their relationship developed.

Ken Howe attended Hope High School and was drafted in March 1968. After completing basic and infantry training he was sent to Vietnam in September, assigned to Company D, 3rd Battalion, 8th Infantry of the 4th Division.

They operated in the general area of Kontum, in the Central Highlands.

In early March 1969, the 66th Division of the North Vietnamese Army moved into the region, and four infantry companies were inserted to block them.

Alpha Company was badly mauled when it was dropped right into the headquarters of the NVA unit. Howe and his Delta Company mates were ordered to assist their beleaguered comrades.

Moving cautiously along a well-worn trail, Howe's platoon ran into a group of NVA soldiers walking toward them. Both sides opened fire and scattered. One of the men with the NVA screamed, “Don’t shoot! Don’t shoot!” and began running toward them. It turned out he was a survivor from Company A who had been captured.

The soldier warned Delta Company not to go any farther: “The NVA are right over this ridge, and they are waiting for you!”

Thus warned, they pulled back to a more defensible position and dug in for the night.

Dawn came, and Howe began to think they were OK — and then all hell broke loose.

“They hit us at 7 a.m. There was a big hardwood tree to my left front. Three other guys were between me and the tree, and one guy was behind the tree.

“The NVA fired an armor-piercing B-40 rocket round into the tree, and it took us all out. I was the least injured of all of us, but I still had shrapnel in my face, elbow, shoulder and back. That's how I got my Purple Heart.”

Two days later, the fighting died down enough to allow wounded to be evacuated.

“I spent six weeks in the hospital,” said Howe. He completed his tour.

Back home, and denial

On the surface he seemed healed, and ready to return to a normal civilian life.

“I got home,” said Howe, “and I got married.”

And then he got divorced. And then he married again; and divorced again. “I've had four divorces,” he said matter-of-factly. “And I’ve been married five times.”

“I swore up and down that Vietnam didn't affect me,” he said. “It wasn’t me. It was everybody else who changed.

“Oh, yeah, I was in denial for a long while. I drove a truck out of Worcester, working 10- to 12-hour days plus commuting. My job helped hide it.”

In the 1980s he joined the Vet Center in Pawtucket, and was a founder of the first Vietnam Veterans of America chapter in Rhode Island.

“But I still was in denial.”

Howe said that PTSD “didn't really bite me in the behind until after I retired.”

“Then it really caught up with me, because I had time to think. It got to the point where I didn't even want to go out of the house.

“I started counseling, and was told, ‘You have to do exposure. Go to Walmart.’ And I couldn't go to Walmart.

“Then I was at the V.A. for a PTSD evaluation, and the examiner gave me a hard time. I finally fell down and yelled, “Don’t [expletive] with me any more!”

Other incidents followed, and Howe finally accepted he had a problem. While trying to figure out what to do, he bumped into a Vietnam brother he hadn't seen for a while.

“He had a dog with him, and he said the dog helped with PTSD.

“That put the bug in my ear. But no one I dealt with at the V.A. seemed to know about service animals.”

The V.A. itself does not provide dogs, but for veterans and dogs who qualify, it provides certain benefits, such as veterinary care.

But the onus is on the veteran to start the process, and find his own dog.

So Howe started looking up service dogs. This was in 2016.

He found potential sources in several states. Some had no dogs available, or there was a long waiting list.

He finally heard back from Service Dogs for America in North Dakota. They would consider his application.

“It took about eight months, but they finally invited me out for an evaluation,” Howe recalls.

“Plan on spending the better part of a month here,” they said.

The first day he filled out grant applications.

“Donors picked up the whole tab,” Howe said gratefully. “That was a $20,000 [price tag, in 2017]; two-plus years of training for the dog, plus lodging, and the cost of somebody training me. Plus my flights.”

Jenny BrodKorb is executive director for Service Dogs for America. A highly qualified dog trainer herself, she spent four years as an officer in the Army’s Medical Service Corps.

“Since I became executive director in 2015 not a single Veteran has had to pay out-of-pocket for his dog,” she told The Journal.

The price tag today is $25,000, and a major element of Service Dogs for America's staff work is generating the funds to support each veteran.

“The cost of training is significant, especially for dogs dealing with issues such as seizures,” BrodKorb said.

As dogs progress, certain animals seem suited for PTSD work, while others become mobility dogs, and still others handle seizures.

The group's website adds, “Occasionally we must decide that a dog is not suitable to become a service dog because of a health or temperament issue.”

“The decision we have to make,” BrodKorb explained, “is whether the animal is more suited to hold down the sofa or to hold up a human.”

Her group calls this the "career change option."

While there is no definite timeframe, three years is the upper limit before a dog goes into career change.

“We must look at a working career of 10 years or so in order to amortize the cost of training,” said BrodKorb.

'You can’t lie to the dog'

Fiona and her sister Evie were donated to the program.

In what sounds like an episode from a Snoopy cartoon about the Daisy Hill Puppy Farm, Evie had an independent streak. They could never break her habit of chasing squirrels and rabbits. So she became a career-change dog.

Although Fiona passed training with flying colors, she had a different problem. She never showed any interest in a potential human life partner.

BrodKorb explained, “We are the only certified service dog training facility where the dog chooses the human.”

The client seeking a dog sits in the middle of an empty room. The trainers are behind a two-way mirror. Dogs are brought in, one at a time, to see how they interact with the human.

In Howe's case, Fiona was brought in as an afterthought.

“We were considering adding her to the career-change list because she was in her third year and had not expressed interest in any of the human candidates,” said BrodKorb.

When Howe went through this process, he said, “Some dogs wouldn't even come near me.”

To everyone’s surprise, Fiona did. So BrodKorb brought them both into the office. Howe was feeling pretty stressed that day.

“You two spend the afternoon together. If everything works out, you'll have a sleepover,” instructed BrodKorb.

“Then she asked me how I was feeling,” said Howe. “So I lied and said I was feeling fine.”

At that moment Fiona came over, picked up her paw and started stroking him. BrodKorb said, "Look, you can lie to yourself and you can lie to me. But you can't lie to the dog."

BrodKorb and other staff love seeing the dogs pick their humans, even though it’s emotional to see them go. In a TV interview last year she said, ”There’s always tears at graduation. Big ol' alligator tears, usually.”

Fiona provides mobility assistance as well

Howe also suffered from neuropathy, which made it difficult for him to walk a straight line. Fiona had been cross trained for PTSD and mobility.

“So they put Fiona in a hard harness, like a seeing-eye dog. And she didn't blink. So every time I go out, that harness keeps me steady and moving in a straight line.”

I asked Howe what difference Fiona has made in his life. “I’m much more confident in public,” he replied. “She's a great icebreaker with people. That immediately helps with strangers.”

He plans to travel to a national 4th Division reunion at the end of July.

V.A. policy is still evolving

The relationship with the V.A. can still be tricky. Confusion exists when it comes to PTSD about the distinction between a service dog (eligible for V.A. benefits) and an emotional support dog (not eligible).

As BrodKorb explained, “A service dog is considered as a medical device, just like a pacemaker or an insulin pump.”

While service dogs go through intensive training by experienced handlers, any pet can be an emotional support animal.

V.A. guidance states, “Service Dogs may be used as additional support for Veterans with PTSD and mobility limitations.”

The operative word is “may,” and the interpretation of those rules can vary from state to state.

Last year Congress passed the PAWS Act, which should help. It established a pilot program in five states to provide dog training to eligible veterans with PTSD “as an element of a … health program for such veterans.”

BrodKorb served on a board that helped write this legislation.

Service Dogs for America is the only service dog training facility right now without a waiting list.

“We have dogs available, and we want to match them with humans,” BrodKorb said.

Calendar

Thursday, 8:30 a.m., Sgt. Adam S. DeCiccio Warwick Memorial Post 272 VFW golf tournament at Cranston Country Club. Shotgun start; $130 per player; individual – Callaway system; foursome, scramble, low gross. Raymond Denisewich, co-chairman, (401) 644-8066 or raymond.denisewich@gmail.com.

Thursday, 2 to 5 p.m., Rhode Island House of Representatives annual Veterans & Military Families Day, in the State House.

Thursday, 5:30 p.m., woodworking class at the Providence Vet Center, 2038 Warwick Ave, Warwick. Vet Center eligibility is required to attend. Contact Paul Santilli, Paul.Santilli@va.gov or (401) 739-0167.

Friday, 7:30 a.m., CSM Edward McConnell annual golf tournament, presented by the Military Police Regimental Association, Rhode Island Chapter, Triggs Memorial Golf Course, 1533 Chalkstone Ave., Providence. For tickets and information go to mprari.org/events-1/mpra-ri-2022-csm-edward-mcconnell-annual-golf-tournament.

To report the outcome of a previous activity, or add a future event to our calendar, email the details (including a contact name and phone number/email address) to veteranscolumn@providencejournal.com.

This article originally appeared on The Providence Journal: Veterans Voice: Service dog a good soldier to Vietnam vet