Veterans Voice: Quest to find vet's unmarked grave a family odyssey

On March 10, the Lennon family will be at St. Charles Cemetery, the parish burial ground associated with the now-closed St Charles Borromeo Church in Woonsocket.

A funeral detail from the Rhode Island National Guard will render honors over a new Spanish-American War headstone, provided by the Veterans Administration, marking the grave of Private Patrick J. Lennon, late of Companies E and I, 1st Rhode Island Volunteer Infantry. He was my Irish-born grandfather.

The quest to find this grave turned into a family odyssey.

As family folklore stories go, this one is a doozy. Patrick allegedly jumped off a British Army troop ship as it left harbor, headed for the wars in southern Africa in the 1890s. He was rescued by the next outbound ship, which was bound for the USA. Ironically, he soon found himself in the U.S. Army instead, headed for Cuba to fight the Spaniards in 1898.

I’m going to share Patrick Lennon’s story as an introduction to the new Providence Journal Veterans Column, as well as to Frank Lennon. It’s important to me that veterans reading this column know that I am one of you, and that as long as I write this section I will fight to ensure that your service, and the sacrifice of your family members, is not forgotten.

I am dismayed, as I’m sure many of you are, at the lack of connection of the average American with anything military. This country has now reared a third generation that cannot tell a colonel from a sergeant, a howitzer from a tank, or a battleship from an aircraft carrier. Even with our extended involvements in Afghanistan and Iraq, only our active soldiers and the direct families of those who deployed seem to have a real comprehension of what it means to serve.

In some small way, I hope to make a dent in that disconnect.

I will also try to make sure that you know about all the benefits and services available through the VA, the military health system, federal and state Departments of Labor, and many other service and benefit programs.

For those of you who are not veterans, I hope to be able to continuously remind you of what we all owe to those who served in our nation’s military.

David Ng: Decorated Green Beret reports for duty as Journal's new veterans columnist

Back in 1999, former Army Chief of Staff Gen. Bernard W. Rogers made a very interesting point about the unique nature of military service in our society.

“A doctor contributes to his patients; a priest to the members of his parish; a lawyer contributes to his clients; a politician to his constituents. But those privileged to wear our nation's uniforms belong to a profession in which every member, every day, makes a contribution – no matter how small – to every citizen of this great land.”

That’s every one of us.

For most of you who did not serve, there is an uncle or a cousin or a grandparent in your family tree who did. I encourage you to learn more about this person, and pass that information on to future generations.

In my case, my father, a lifelong Rhode Island National Guard soldier, served in World War II, earning a battlefield promotion to colonel. My uncle Leo Gaffney went to France in 1917 with Battery A of the 103rd Field Artillery. My great grand uncle, Terence McQueeney, served with the 4th Rhode Island Infantry during the Civil War.

And then there’s our family ghost — my grandfather, who may or may not have served in the British Army, and who may or may not have been an American soldier during the war against Spain.

I can remember my father embellishing the details a bit, describing the tactic used by British recruiting sergeants to meet their quotas in Irish villages. They would invite an unsuspecting lad into the pub, and get him drunk to the point of passing out. When he came to, he would find a coin in the bottom of his empty glass, representing his recruiting bonus. Having thus “taken the Queen’s shilling,” Patrick found himself impressed into British Army service.

While the Ireland story sounded good, there was no way, back in the day, to prove or disprove it. Patrick died in 1908, when my father was 4 years old — and the fourth of five children. His mother, Mary, did not talk much about her dead husband, and she died in 1943, while my father was serving in Italy.

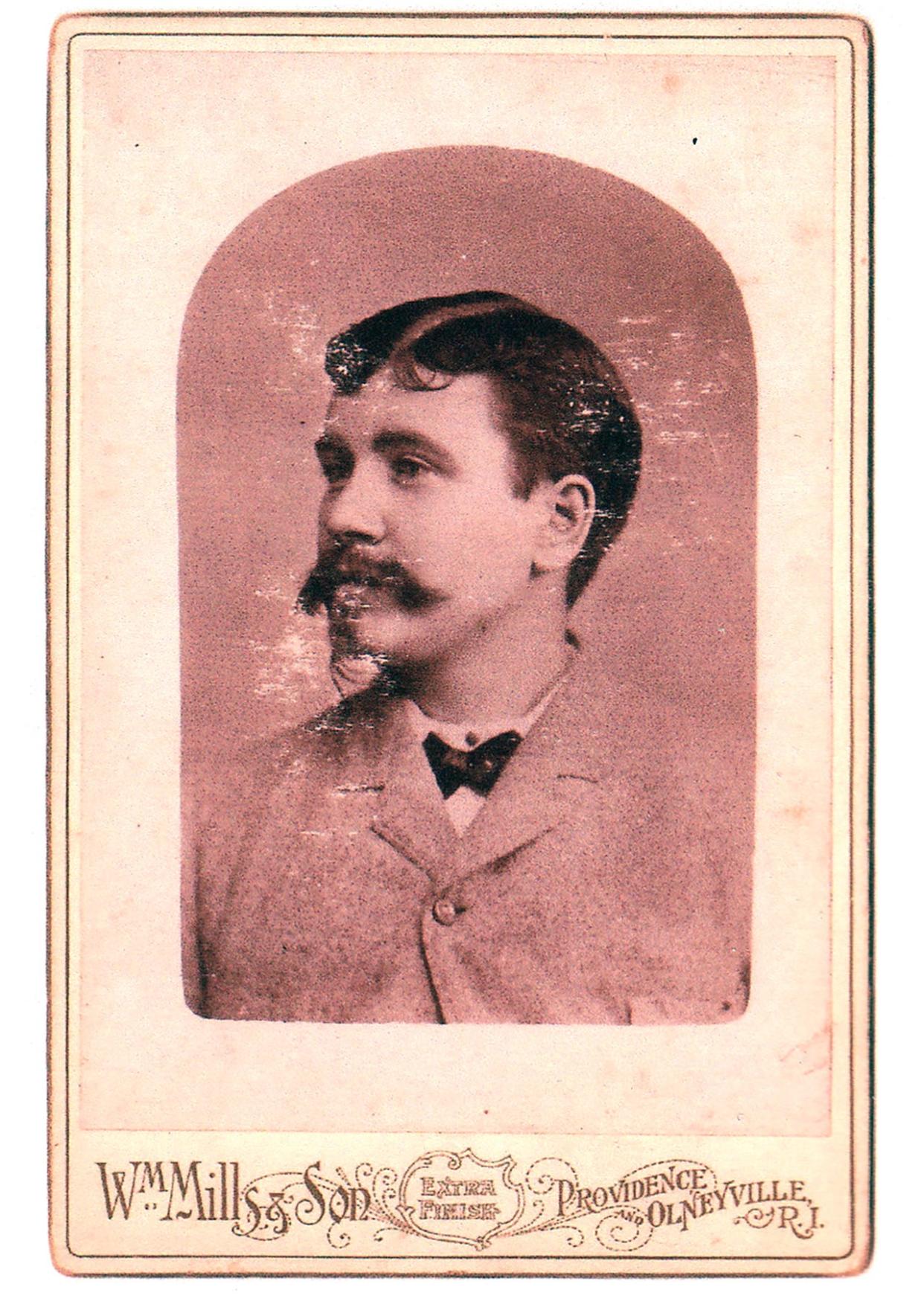

Patrick’s U.S. Army service was another story, however. My dad had a photo of his father with a number of other soldiers, a sepia image mounted on a dog-eared piece of cardboard. He gave it to me, and at the time I did not truly appreciate its importance. I took it to West Point, and somewhere between the Academy and my assignment to Berlin, the photo disappeared.

Fast forward some 50 years, and for some reason our little family became inspired to research our family history. My sister Sheila Lennon was an internet whiz from the beginning, and her daughter Casey Dahm quickly became an excellent genealogical researcher.

My mother’s family, the McQuillians, were “lace-curtain Irish” who had begun to arrive in America before the Civil War, and we were able to learn a lot about them fairly quickly. The Lennons, however, were another story.

Trying to find out who the Lennons were and where they came from, we were chastened to uncover more than our share of relatives using false names for unknown reasons. A few had been jailed for drunkenness and other petty charges, and there were tales of illegitimate children as well. Clearly this side of the family favored the “shanty Irish” moniker.

Hundreds of research hours and two more trips to Ireland followed. The dead ends and contradictions just reinforced our commitment to sort out the Lennon puzzle.

After several years of on-again, off-again effort, we finally had a pretty good idea of the shape of our family tree. But one detail still eluded us: we had no idea where our grandfather Patrick Lennon was buried.

If he was in fact a Spanish-American War veteran, I wanted to make sure there was a flag on his grave on Memorial Day.

We knew he had been born in County Longford, Ireland, in March 1872; that he had come to America in the 1890s; and that he had married Mary Rodgers at Blessed Sacrament Church in Providence in 1899. We also knew that he died when my father was about 4 years old, meaning around 1908. But we had no idea how and where he died. It was puzzling — there was no Rhode Island burial record.

I finally found a copy of a letter notifying the War Department that Mary Lennon had died in December 1943, and that they should stop sending her monthly widow’s pension payment.

Pension?

That confirmed Patrick really was a veteran of the Spanish-American War. I filed a Freedom of Information Act request with the National Archives, and several months later received a thick file which included a goldmine of previously unknown family data. It also showed my grandmother’s tenacity in the face of bureaucratic hurdles.

For those of you who are daunted or discouraged by the paperwork obstacles often involved in a VA compensation claim today, consider Mary Lennon’s case.

It turns out that when Patrick enlisted in the 1st Rhode Island Volunteers in 1898, he did so under his brother’s name: Francis J. Lennon, who happened to still be in Ireland at the time. No one knows why he did this, but because he did, it took 16 years to resolve the pension claim!

Mary filed her initial claim in 1917, when Congress first authorized Spanish-American War pensions. The chain of correspondence and documents in the file includes affidavits from other soldiers he served with, statements from Mary and other family members and even a pay receipt he signed so that his signature could be compared.

The War Department finally decided in her favor in 1933, and she began receiving a monthly stipend of $15.

For our purposes today, the most important document in the pension file was Patrick’s death certificate, which showed he had been buried in St. Charles Cemetery — in Blackstone, Massachusetts.

While the church was in Rhode Island, its cemetery was across the border, and that explained why we could find no burial record. We were searching in the wrong state archives.

I went to the parish office, and after some searching they found that he had, indeed, been interred at St. Charles. The good news was they had a section and plot number: 6W, grave 53. The bad news: it was an unmarked grave.

Now that we had the pension records, we knew he was eligible for a VA marker and headstone. We could not get the headstone, however, until the cemetery could precisely locate his remains, and send a confirmation to the VA.

The news got worse. No one knew where Section 6W was. It was an old designation that did not appear on any of the cemetery maps. While we were trying to solve that mystery, the diocese shut down St. Charles parish, in 2020. All records were transferred to All Saints parish, where we had to start over.

Thanks to the support of Father Phil Salois, Father Ryan Simas and some dogged work by office manager Deb Doris, the gravesite was finally located last June. Ms. Doris emailed the good news and later described the search. She and two cemetery employees “walked a few sections until we found it.” She brought her laptop and they used all the marked graves as reference points.

“I stayed on the laptop and the guys walkie-talkied names to me until we found the right spot.”

Based on the certification from the cemetery, the VA shipped the headstone. It was installed in October. The combination of holiday schedules, COVID-19 and weather caused us to put off the dedication until spring. We chose March 10 because that was the 150th anniversary of Patrick’s birth.

And what about the story of his leap from the British troopship, choosing the unknown rather than being shipped to South Africa? That could not have been true … or could it?

Much to my amazement, a search of British military records turned up a Patrick Lennon, age 17 with a March birthday, recruited from County Longford in 1890 into the 6th Battalion of the Rifle Brigade (The Prince Consort's Own). Until 1882 this unit had been known as the Royal Longford Rifles (formal name Prince of Wales Royal Regiment of Longford Rifles).

Interestingly enough, this was the first unit in the British Army to not wear red coats. (Fittingly, they wore green with black trim).

Elements of the Rifle Brigade were sent to the Sudan in 1896 to quell the Mahdi uprising. I can just imagine a situation in which Patrick, nearing the end of his six-year enlistment, might not want to take the chance of being sent there.

VFW of Rhode Island youth scholarship program winners

The theme for the high-school competition was “America: where do we go from here?” Winners were: 1st place, Megan Chevalier, 11th grade, Portsmouth High School; 2nd place, Mia Holroyd, 12th grade, Smithfield High School; and 3rd place, Sophia Selva, 11th Grade, North Kingstown High School.

The middle-school contest theme was “How can I be a good American?” Winners were: 1st place, Harrison Fallon, 7th Grade, Winman Middle School, Warwick; 2nd place, Alexa Buco, 6th Grade, Birchwood Middle School, North Providence; and 3rd place, Celina Medeiros, 6th Grade, Tiverton Middle School.

All winners will receive a cash prize, certificate and medal, and a citation from Gov. Dan McKee. First-place winners will also represent Rhode Island in a national competition.

North Kingstown VFW Post to host Winter Warrior softball tournament

Teams will play an abbreviated double-elimination tournament format, with the first games starting at 9 a.m. Saturday, Feb. 12. All games will be at Ryan Park, Oak Hill Road, North Kingstown. Proceeds will be be donated to Veterans Inc. to support homeless Rhode Island veterans. Veteran groups, churches, local softball teams, and other community members are invited. Free hot cocoa and hot apple cider will be provided. Full details can be found at VFW152.org. Contact David Ainslie at ainslied68@gmail.com

Cleanup at Exeter Veterans Cemetery

Veterans Memorial Cemetery staff will be cleaning up holiday decorations and wreaths during the week starting Jan. 31. If your family has placed something on a gravesite that you wish to save, please do so no later than Sunday. After that date, normal cemetery rules will apply: each grave may have one potted plant in a plastic container less than 8 inches in diameter, or a single plastic cone vase for flowers (natural or silk). The vases are available in a green bin outside the administration office.

RI Veterans Calendar

Fridays, noon to 1 p.m., “Yoga for the Military,” Warwick Vet Center, 2038 Warwick Ave., Vet Center services required, all levels welcome, yoga mats and blocks provided. Contact Paul Santilli, (401) 739-0167.

Saturday, 1 to 4 p.m., “Open House,” Department of Rhode Island Marine Corps League, Cranston Fraternal Order of Police, 1344 Cranston St., Cranston. Contact Patrick Maguire at rijarhead3533@gmail.com.

Email announcements or future events to veteranscolumn@providencejournal.com. Please include a contact name and phone number/email address.

This article originally appeared on The Providence Journal: Veterans Voice: Search for this vet's unmarked grave was personal