Who are the victors? Reliving the Wolverines’ 1892 ‘win’ over Oberlin

GRAND RAPIDS, Mich. (WOOD) — With Saturday’s 31-24 victory over Maryland, the Michigan Wolverines earned their 1,000th win — the first collegiate program to ever reach that milestone.

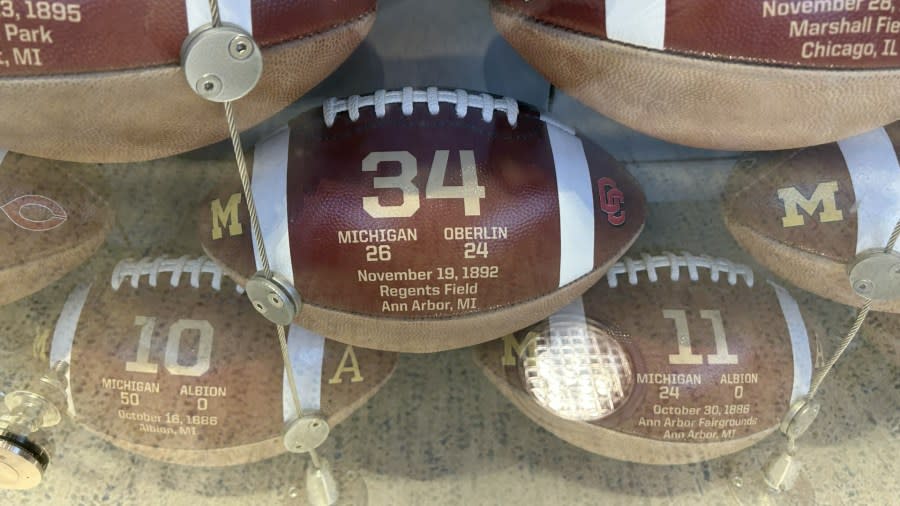

It also means another ball will be added to Schembechler Hall’s “Wall of Wins” — a glass case lined with decorative footballs that mark each of the team’s victories. There are plenty of notable games among them: Win 109 — the 49-0 Rose Bowl win over Stanford that cemented the Wolverines’ dominance under Fielding Yost. Win 395 — another 49-0 Rose Bowl win, this time over Southern Cal, giving Fritz Crisler’s “Mad Magicians” a national title.

Then there are games that define the program, like Win 517: Bo Schembechler’s shocking upset over his former mentor, a 24-12 victory against Woody Hayes’ Ohio State Buckeyes. Or Win 775: the 1997 battle with Ohio State that sealed Charles Woodson’s Heisman campaign.

But at the lowest rungs of the ladder, one game stands out: Win 34.

On the surface — and in the record books — it’s just another game. But the backstory is truly bizarre, one where both teams left the field adamant that they had won, and something they still claim more than a century later.

To understand exactly what happened that day — Nov. 19, 1892 — you have to understand that era of college football. Unlike today, where most teams belong to conferences and every team is governed by the National Collegiate Athletic Association, there was little oversight. Most of the top programs we know today hadn’t been formed. Football was a growing sport that was still in its early stages.

Though there is some debate, the general consensus says the first college football game was played in 1869 between Rutgers and Princeton. It was played with a soccer ball and looked more like a rugby match. Instead of touchdowns, teams were awarded a point for every “score” — giving Rutgers a 6-4 win.

By 1892, the game had made some strides closer to modern football, but Michigan historian Greg Dooley said the game would still be hard to recognize.

“Between the eastern schools and Walter Camp, they were still kind of toying with not only the points system, but the rules of the game,” Dooley told News 8. “You couldn’t advance the ball with a forward pass. It wasn’t exactly a rugby scrum back then, but it was a scrum and very violent.”

NOV. 19, 1892

Heading into the 1892 season, the Wolverines were considered a team on the rise. They were an established program, playing their first games in 1879. And while they weren’t considered on the same level of the Ivy League schools that helped develop the sport, the Wolverines were climbing the ranks — considered among the “champions of the west.”

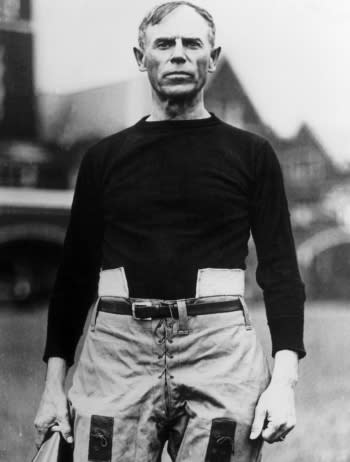

The Oberlin program was anything but established. The football team was started just one year prior, but they brought in John Heisman — yes, that Heisman — as their coach who quickly developed them into contenders.

The two teams met on Nov. 19, 1892, on a cold, rainy day in Ann Arbor. According to Oberlin’s records, both teams agreed ahead of time that regardless of what the game clock read, the match must end by 4:50 p.m. so the “O-men” could catch the last train out of town.

“This type of agreement was not without precedent,” an Oberlin report reads. “The two teams made this same arrangement the year before in 1891.”

Penalties, turnovers and the poor weather slowed the game down, but at 4:49 — according to Oberlin — and with the game tied 22-22, Oberlin kicked a “quick goal” for two more points.

Immediately afterward, a backup Oberlin player – who served as the referee and timekeeper – called off the rest of the game, saying the clock had struck 4:50. Claiming the victory, the Oberlin team walked off the field. However, the game’s umpire — a Michigan reserve — had the time marked at 4:46. With no opponent, the Wolverines were allowed to march down the field for a “touchdown” to claim a 26-24 win.

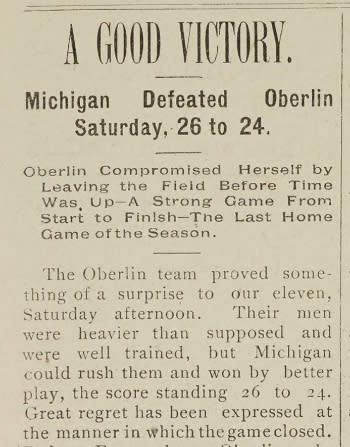

The game report in The Michigan Daily student newspaper said, “great regret has been expressed at the manner in which the game closed.”

“Captain Williams called his men off the field, and they immediately got into the bus and were driven to their hotel,” the report stated. “Before the men could line up again Referee Ensworth called time and Oberlin ran off the field so quickly that it almost seemed pre-arranged. Jewett walked over Oberlin’s line with the ball for Michigan’s fifth touchdown, making the score 26 to 24 in Michigan’s favor.”

The game is now a small footnote in Michigan history but stands as one of the high achievements for Oberlin. For one, it was the crowning finale on the team’s undefeated season. Plus, the program, which originally served as one of the founders of Ohio’s “Big 6 Conference,” eventually faded as the university shifted its focus away from top-tier athletics. Now known as the Yeomen, Oberlin plays NCAA Division III football.

SCHEDULING THE REMATCH

Perhaps as interesting as the 1892 matchup, Michigan and Oberlin played again in 1894, with both sides eager to clear up any doubts with a resounding second victory. According to Dooley, they also went into the match with the intention of playing a fair game. The Wolverines got the last laugh, a 14-6 win, but their attempt at fair play nearly cost the team down the road and led to more calls for outside oversight.

“The memory of (the 1892 game) was in everyone’s mind. So the teams got together and said we need an umpire for this game to make sure this doesn’t happen again. And they decided on Amos Alonzo Stagg,” Dooley said.

Like Heisman, Stagg is a college football forefather. He played five years at Yale before becoming an iconic head coach, including 40 seasons at the University of Chicago, the team that became Michigan’s top rival of that era.

Between working the Oberlin game and some other advanced scouting, Stagg’s Maroons were ready for their Thanksgiving Day showdown with the Wolverines.

“Stagg umpired the game in November of 1894. Michigan played Cornell shortly after and Stagg went to that game, and he brought two of his players to scout Michigan. Then they met on Thanksgiving Day of 1894. (The Wolverines) played Chicago and the Chicago team knew all of their play signals,” Dooley said.

Fortunately for the fans in blue, the Wolverines picked up on it and used that knowledge to their advantage.

“They would put guys over here and (Chicago) wouldn’t even put anybody over there to guard them or stop a run that might go that way,” Dooley explained. “At the very end of the game, because you weren’t supposed to coach from the sideline, they basically whispered the call to the halfback, yelled out the signal, which was going the other way, and handed it to the halfback who ran and scored.”

After the game, Stagg admitted that he and his team knew the Wolverines’ “tendencies.” While severe injuries and fatalities were the key motivator to bring oversight to college football, gamesmanship was also a factor. The conference we now know as the Big Ten was founded within months of the game. The NCAA was born in 1906 with an expressed mission to shape the rules and safety regulations for the game.

For the latest news, weather, sports, and streaming video, head to WOODTV.com.