Video games came between me and my son in the pandemic. Could they bring us back together?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Listen to this story:

This is the story of a journey from ignorance to understanding. It’s about questioning beliefs, and radical rethinking. It’s about parenthood and childhood and the pandemic.

But ultimately, it’s about video games.

My 12-year-old son has always loved video games, but during the pandemic that love intensified. After hours of staring at a screen for Zoom school, he couldn’t wait to open his laptop again to play "Minecraft," Roblox or "Pixel Gun 3D." At the dinner table he often reported that the best thing that happened to him that day occurred in the virtual world.

For me, computers represent work and endless social media posts. How was I even related to this kid who loved nothing more than putting on headphones and disappearing into technology? And what kind of mother was I that I was allowing him to do it?

To get him out of the house, we took walks in the evening. I’d ask if he’d heard from his friends. He’d talk about games. Did I think he should buy a military helicopter with missiles or a high-speed airplane in "Mad City"? The airplane was faster, but the helicopter would be more useful for breaking his friends out of jail.

Sometimes I let him keep talking while my mind wandered. Other times I asked if we could change the subject.

“Video games are pretty much the only thing that makes me happy right now,” he said one day.

That was a gut punch. I felt I had failed as a parent.

My husband said it was normal for boys my son’s age to love video games this much. I wouldn’t know.

I grew up the eldest of four sisters in a house with an original Nintendo system in the den. We played "Super Mario Bros." and "Duck Hunt." The wall next to the television was pockmarked from where I threw the controller in frustration. By the time I turned 14, I’d concluded video games were not for me.

Now, I looked at my son and wondered: Who was this kid who seemed most alive, most himself, while shouting at his friends to follow him into the Nether portal in "Minecraft"?

I know I’m not alone.

One friend told me how baffled she felt when her daughter set an alarm for 6 a.m. so she could be among the first to explore a new world dropping in her favorite video game. A couple who don’t own a TV confessed they had bought their son a Nintendo Switch during the pandemic so he could meet up with friends virtually.

Another friend told me her son’s therapist had said increased interest in video games is a natural response to a world that feels as though it’s crumbling. After all, there’s no virus in Roblox.

My younger son even made a video for his school that captures the dynamic playing out in many homes: A harried mother in a beehive wig complains with wild arm gestures while her son keeps playing on more and more devices, completely ignoring her rants.

I sent it to a friend in Seattle. He wrote back, “This hits a little too close to home.”

The solidarity helped, but I needed things to change between my older son and me. And so, I reached out to the experts.

Julia Storm is a digital media wellness educator (yes, it's a thing) who runs ReConnect, a business in Los Angeles that helps struggling parents and kids navigate our digital age.

“As parents we want to ensure that our children are developing socially and emotionally in the best way possible,” Storm said. “When we see this third party — whether it’s a video game or a phone — exerting so much influence over our children, it’s anxiety-inducing.”

And for adults who struggle themselves to resist checking email or scrolling through Instagram, it can be extra scary to watch a kid fall prey to those same forces.

“Kids don’t have the brain development to withstand the algorithms and design of a lot of these games,” Storm said. “Many adults don’t have that ability either.”

Part of her job is reminding concerned parents that not all screen time is bad.

When she starts working with a family, she poses key questions: Is the child sleeping enough? Eating a healthy diet? Exercising at least a little bit every day? Connecting with friends? Helping around the house?

“If they’re hitting all of those and they’re doing some screen time, I’m less worried,” she said.

But Storm also laid out some indicators of a genuine problem: an inability to stop playing, severe mood swings when he or she does stop, sneaking video games and growing more isolated and solitary.

“Those are all signs that something's out of balance,” she said.

When we hung up, I took stock of my kid’s behavior. He was sleeping fine. He’s generally a healthy eater. He doesn’t exercise every day, but when we suggest he take a walk or a run, he’s usually happy to do it. He was always energized when he saw friends in person. And though he might grumble about chores, he does them.

I also thought about something else Storm said — that she’s giving her own kids a pass for spending more time on video games in the pandemic.

“It’s one of the only ways they can safely play with their friends,” she said. “I'd rather have kids interact in some form with other children than not interact at all.”

Next I spoke with Sinem Siyahhan, a professor of educational technology at Cal State San Marcos, where she studies how video games promote communication, connection and learning between parents and kids.

Siyahhan sees video games as a natural extension of the games families have long played together — Go Fish, Monopoly, even tossing a ball back and forth.

“Play is a family routine; it’s part of family life,” she said. “And it’s cross-cultural. Every culture plays games.”

She agrees that parents should monitor the video games their kids play, just like they might track their reading and viewing habits, but she resents the popular demonization of video games and screen time in general.

“Kids learn through play as part of their way of connecting to the world,” Siyahhan said. “What happens over time is your play experience evolves. I see video games as a part of this evolution.”

It's a point of view that has recently become more mainstream. Before 2016, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommended no more than two hours of screen time per day for children ages 5 to 17. Now it recommends that families work together to create a media use plan that takes into account a range of factors, including a kid's health, personality and the family's values.

Siyahhan also advises parents to start playing those games with them. This gives parents an opportunity to model behaviors around overcoming frustration and dealing with failure — skills that are useful in the real world too. (Clearly not a time to mention my throwing the Nintendo controller against the wall.)

But if logging into Roblox is too much for some parents, she says they should at least talk to their kids about the games they play.

“Asking someone to talk about a game they play is the same as asking them about a recent book they read,” she said. “It's meaningful for that person.”

As Siyahhan spoke, I thought about how it’s an act of generosity to give people the space to talk about the things they care about. Surely I could offer that to my son, couldn't I? That night, I asked him to name his five favorite games in Roblox.

He sat up in bed.

“That’s a really good question, Mom,” he said.

Finally, I reached out to my friend Todd Martens, who reviews video games for the Los Angeles Times.

Over Slack, I told him how heavily my kid was relying on video games during the pandemic — and that my gut was telling me this was a bad thing.

“Your gut is wrong,” he wrote back. “Play is how we learn.”

When Martens was little, he told me later, his dad used to read books to him. But as he got older, reading time morphed into game time.

“My dad would get home from work late, at like 10 o'clock at night, and then we would play for an hour,” he said. “And that was like our book."

Martens was an extremely shy child who had trouble talking to his peers and teachers. But when father and son played narrative games, like "King’s Quest" or "Monkey Island," he came out of his shell.

“My dad would say, ‘What should we do? Where should we go?’ And I got the sense that I was writing the story,” he said. “I feel like because my dad engaged me and prompted me, it allowed me to have more confidence in my own creativity.”

Martens then offered a surprising analogy: “It was the same sensation emotionally as like when we would go to a Cubs game together.”

A few weeks ago my son came into the kitchen with a proposition.

“Mom, we should play a video game together,” he said. “I think it would be really fun.”

I wasn’t so sure, but when your 12-year-old kid says he actually wants to spend time with you, it’s hard to say no.

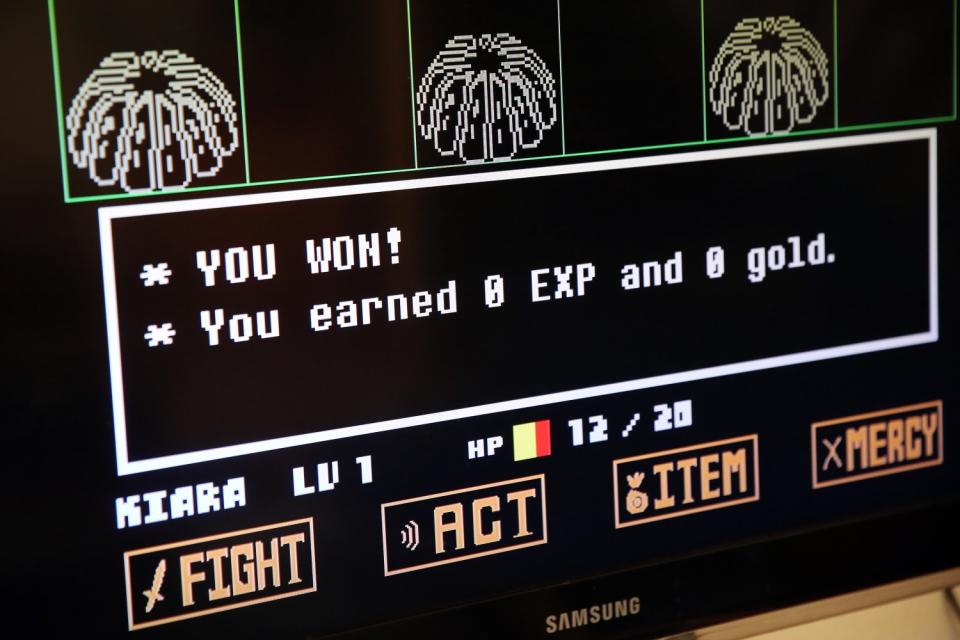

We settled on the role-playing game "Undertale," in which together we inhabit the character of Kiara (we chose the name), a kid of indeterminate gender who falls into a hole in a mountain where monsters were banished by humans after an ancient war.

To battle our way out of the mountain, we often traveled by riverboat, made friends with a skeleton named Sans, killed our first mentor (we didn't seem to have any other choice), received help from a scientist who seemed to have a giant crush on us, and purchased a lot of Cinnamon Bunnies to give us energy.

I wouldn’t say I’m a convert, but I don’t hate it, either. The characters are funny, and I like exploring this strange virtual world. My kid is better at fighting the monsters and solving puzzles than I am. I’m better at keeping my cool — and calming him down — when the game gets tense.

“Real life is way too stressful for me to get stressed out over a game,” I tell him.

Recently, I asked my son if he thinks I’m as fun to play video games with as his friends.

“Definitely,” he said. “If not more fun.”

Me?

“Even though I’m not awesome at video games?”

“Yeah, I like this because I’m not playing competitively with you," he said. "My friends are very competitive, but you are nice and simple, and I like that.”

This mom had just leveled up.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.