A view of history: What life was like at Forest Hills in Wilmington during World War II

Daydreams frequently enticed my wartime school-day imagination to wander from its second-floor classroom desk to the Pacific jungles or North African desert.

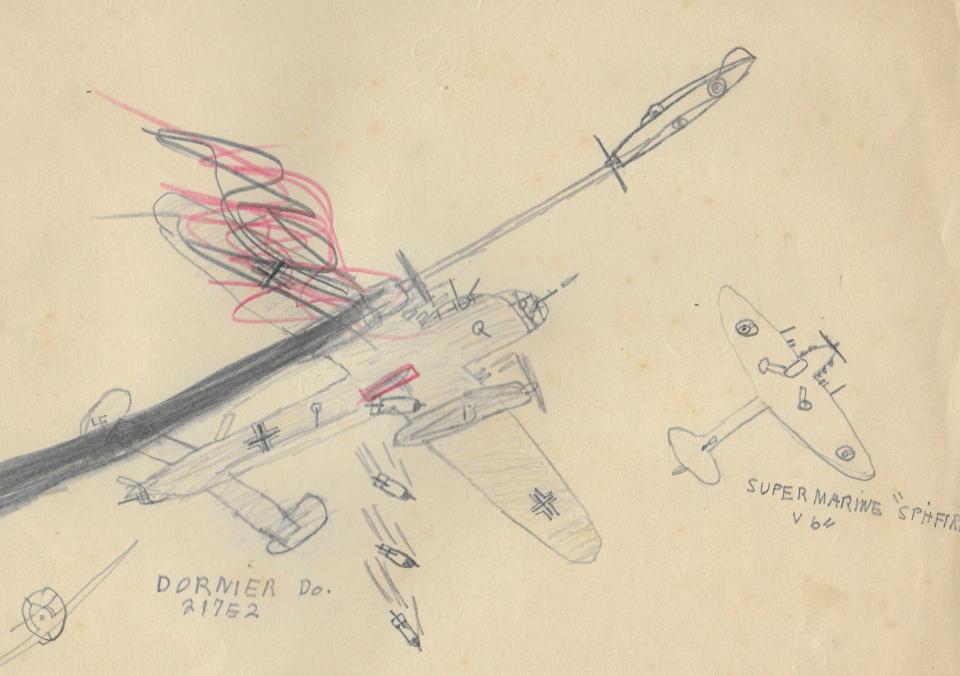

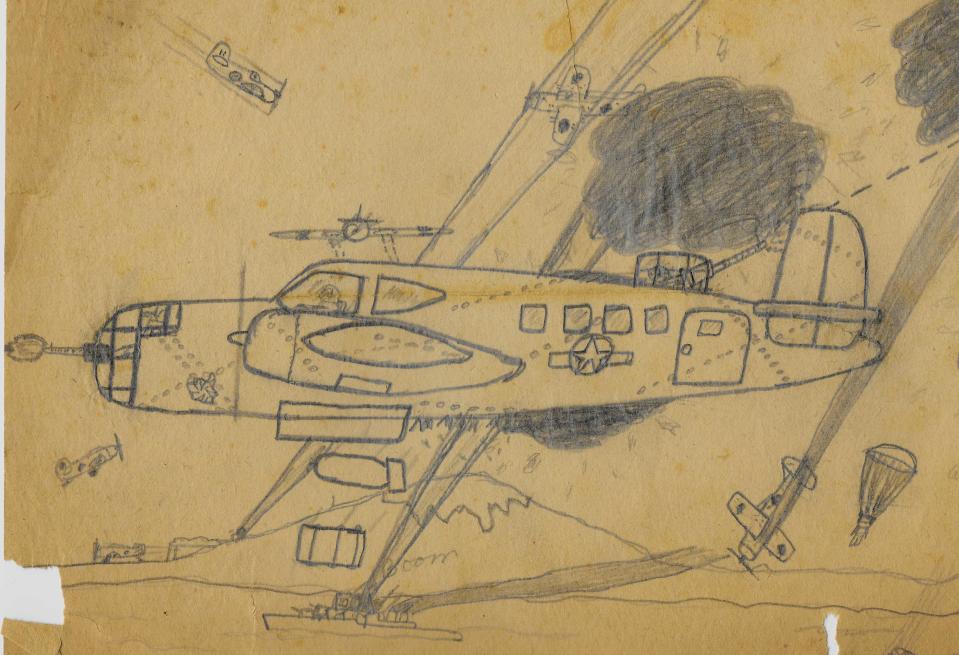

While staring out the window into the pines, lacking artistic capabilities never deterred the need to sketch my vision hurriedly. Battle scenes. Enemy planes in flames. Enemy troops blasted. Our side winning.

Yes, I should have been completing my assignments instead.

Convincingly, this artwork spurred the war effort. The many sketches I’ve retained still puzzle me: Why teachers didn’t confiscate more. How did I get away with even these? For the war effort.

During World War II, I lived with my parents and dog Jip at 102 Colonial Drive in Forest Hills, today a house Daddy built in 1936.

Neighborhood kids walked to and from school. Took me probably 12 minutes to go the long block past “the point” and over Burnt Mill Creek – unless stopping to pet someone’s dog or plan war games with a buddy, or facing the music at home.

Buses transported some kids from war-housing Maffitt Village.

In 1942 the government constructed that second floor to accommodate the increasing student population. Without air conditioning, we opened windows and transoms. Today’s gleaming white entrance columns and stately pines sketch their own memories of those days.

The Gestapo agents

My 1942-44 teachers included principal Katherine Von Glahn, Harriett McDonald, Emma Nauer, and Caroline Newbold. Three were neighbors, too close.

Our class liked Newbold, young, no education degree, green. We threshold teenagers pestered her. Decades later she said, “Discipline was a problem. I was sort of an emergency teacher. Miss Von Glahn would lay down the law, not Miss Newbold. You kids drove me out of teaching.”

After two years, my father hired her at his downtown savings and loan where she met her husband, a lawyer in that building.

Von Glahn and Nauer convinced us boys they were German Gestapo agents. (Their names, demeanor, surveillance, omnipresence.) Structure and discipline ruled, like McDonald, whose ruler pounded tables demanding attention.

George Rountree remembered Von Glahn swatting him with a ruler after carving initials into his desk. She called his mother, who “beat the living daylights out of me.” The principal punished students for acts en-route to school, like throwing firecrackers at girls.

My gosh. Whatever it takes, avoid her office. McDonald pulled me from an auditorium event and whisked to the Von Glahn torture chamber. Another infraction.* I did “cause trouble.” See my “Conduct” report cards. The inevitable parents note went home, guaranteeing unmentionable wrath.

*Skjn-crawling, scratch-scraping fingernails across the black chalkboards launched girls into a tizzy.

War bonds and stamps

Pushing the sales of war bonds and stamps inspired student roles in the war effort. We felt extra productive. The most popular bond, costing $18.75, redeemed later for $25. I exchanged my several ones long after the war.

Schools competed, and classes within schools. The prime sales targets: Parents, of course, and neighbors.

You pasted individual $0.10 stamps into a coupon album covering the dreaded likenesses of Tojo, Mussolini, and Hitler, and exchanged a completed album for that bond.

Kids loved to obliterate those guys. For the war effort. I still treasure a booklet (they’re rare) with those scowling, comical enemies.

Each Forest Hills class encouraged full participation buying stamps. For classmates without resources, Dr. William Dosher bought stamps in their name.

County students sold $23,174 in bonds during the 1943 drive. Chestnut Street sold $11,150.60, but Forest Hills only $329.20. That January, Washington Catlett earned the U.S. Treasury Minute Man flag recognizing 90% participation. That March, Lake Forest “contributed” two jeeps by selling $2,191.70 in stamps.

In February 1944, 1,300 children attended a Bailey Theater cartoon-comedy show rewarding them for obtaining citizen pledges to convert stamp albums into bonds.

Air raid drills

The basement cafeteria served as our air raid shelter. For periodic drills, kids who could afford one brought a blanket to lie on. We tucked our heads between our legs and hunched over. Ready if it came.

Besides teacher and classroom shortages, inevitably schools faced serious 1943 area food shortages. Many children depended upon school lunches because of rationing. Parents working defense industry shifts lacked preparation time.

My mother packed a sandwich for my lunch in one of those classic tin boxes. Occasionally I ate in the cafeteria.

More: Two developers tied to Cape Fear west bank projects have history of lawsuits, bankruptcies

More: Catch up with Wilmington history with this guide to all Cape Fear Unearthed episodes

Boys and girls played on opposite sides of the playground, by choice rather than rule. We produced continuous stage productions to occupy us and raise money for worthy causes. Mothers dominated the Parent Teachers Association, which worked hard on war relief drives.

Christmas pageants highlighted that season. Everybody except the youngest had roles. Eighth graders landed Mary and Joseph.

Ronnie Phelps started a band with a trumpet from his Navy brother. “He wanted me to be Harry James,” and loved playing “Onward Christian Soldiers.” We were a religiously-integrated school, all alike.

Without much voice, I tried the glee club anyway, but relished college fight songs and “Hit Parade” winners like “Mairzy Doats” and “Pistol Packin’ Mama.” Today I live for 1940s music.

One classmate said at his previous Sunset Park some kids didn’t have shoes. He took his off not to be different, resulting in constant ringworm.

We supported the 1944 Russian War Relief Drive with used clothing and other items weighing 825 pounds, and felt closer to distant allies. In April 1945 we gathered closet extras for another national drive.

The world of tomorrow

As school opened in August 1945, the StarNews editorialized. “School children were subject to the war’s influence and suffered grave emotional reactions. So many had fathers or brothers or uncles in the armed forces. So many felt their first deep sorrow on learning that loved ones would never come home.

“It would be inane to claim that because the battles were far away the children were unaffected by the holocaust. Violent death in combat will no longer engage children’s hearts and imaginations.

“We have not done so well with the world of today. It will devolve upon them to do better with the world of tomorrow. Their success will depend upon the way they are prepared.”

Discipline, order, country - and reading, writing, and arithmetic. Our teachers did their jobs. We got through it. My life began maturing.

At least five of us from the 1947 class of 31 remain.

- - - - - - - - - -

Wilbur Jones, a Wilmington native, military historian, and retired Navy captain, grew up here during World War II. His 19th book is his memoir: “The Day I lost President Ford: Memoir of a Born-and-Bred Carolina Tar Heel.” See more at wilburjones.com.

This article originally appeared on Wilmington StarNews: Wilmington's Forest Hills school during World War II