Viewpoint: My American friend is a man worth remembering in times like these

Recent political arguments about the place of immigrants and refugees in the United States have me thinking about my friend Tam, a refugee from Vietnam.

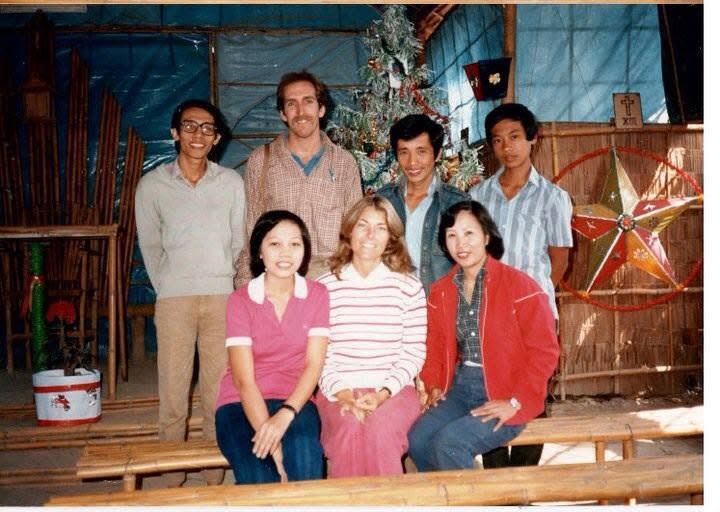

I first met Tam and his family in a crowded Thailand refugee camp in the mid-1980s. The family had fled Vietnam, unwilling to live under a Communist dictatorship. When I met them, they were living under a patchwork of blue plastic tarps donated by Western aid organizations. They had few possessions, and food was scarce. Yet when I told them I was an American visitor to the camp, they insisted I stay to share a meal.

Tam was in his mid-thirties when we met. He was soft-spoken, wore oversized eyeglasses, and smiled continually. He looked painfully thin. He had been a college student in Vietnam, and his English was excellent. He was curious about life in the U.S and asked many questions. We finished the meal, shook hands, and I said goodbye. I assumed I’d never see him again.

In those days, I worked in a refugee camp in the Philippines preparing Southeast Asian refugees for resettlement in the U.S. One afternoon, I received a message that someone was waiting to see me. It was Tam. With a big smile, he told me his family had been transferred to the Philippine camp, where they would spend three months before relocating to California.

I got to know Tam well in the years that followed. My wife and I visited his family after they resettled in California, and he made one trip to South Bend, bringing far too many gifts for my children. Over time, he told me about his past. I learned that my gentle friend had lived a life worthy of a Hollywood movie, if Hollywood made movies about such improbable heroes.

Three times, Tam tried to leave communist Vietnam by boat. Each time, he was arrested and jailed. Each time, he managed to bribe or talk his way out of jail, only to plot his next escape.

Finally, Tam and his family decided to leave Vietnam by walking across Cambodia to Thailand, a treacherous journey. But before they reached the Thai border, they were captured by Khmer Rouge soldiers, whose Marxist leaders were waging a genocidal campaign against their perceived enemies. The family was marched to a forced labor camp, where they were imprisoned for one year, working in the fields from sunrise to sunset.

One night, a group of Khmer Rouge soldiers came to the barracks where Tam and other Vietnamese were confined. A young Vietnamese woman was among the prisoners, and the soldiers took her away. They sexually assaulted her. The following night, they came back again. Tam blocked their path. You can’t take her, he said. She is sick. One of the soldiers jammed a rifle into Tam’s chest. You can’t take her, Tam repeated. He did not back down, and the soldiers left. I like to think they were intimidated by the slender man in eyeglasses who would not move.

Soon after Tam arrived in the U.S., he got a job developing photos in one of those one-hour kiosks. He worked there until he saved and borrowed enough money to buy the camera store across the street. Business was good, and Tam and the family bought a home. But then came smartphones, and people no longer needed to buy cameras. The store failed, and Tam lost everything.

He bounced back. He worked odd jobs until he could start a second business — a restaurant specializing in the Vietnamese noodle dish, pho. The entire family worked there, and the restaurant thrived. They opened a second restaurant. The Yelp reviews were glowing.

Tam and I traded emails and phone calls over the years. I kept promising I’d come to California to visit. Then I got a call telling me Tam passed away unexpectedly. I went to the funeral, so I guess I kept my promise, empty as it was.

Tam was intelligent, brave and resilient. He liked to play his guitar, drink beer with friends and root for his beloved San Diego Chargers. He was forever optimistic and believed fervently in this country. He was the most American person I have ever known.

He is a man worth remembering in times like these.

John Duffy is a professor of English at the University of Notre Dame. In the 1980s, he worked in refugee camps in Thailand and the Philippines. The views expressed in this essay are his own.

This article originally appeared on South Bend Tribune: Arguments about immigrants have me thinking about a refugee friend.