What Viktor Orbán's CPAC appearance tells us about Trump, GOP

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

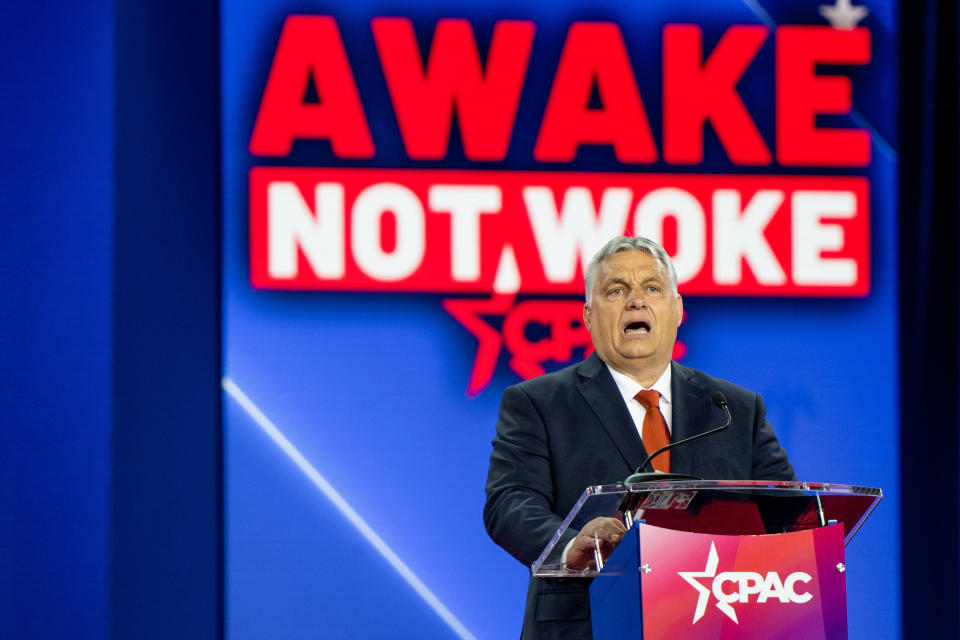

He has extolled the value of racial purity, is vehemently anti-immigration, has cultivated close ties with Russia’s Vladimir Putin and was a speaker at this week’s Conservative Political Action Conference, known as CPAC, in Dallas.

Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, 59, is widely criticized around the world for systematically dismantling his country’s nascent democracy during his 12 years in power — but that hasn’t stopped him from emerging as a darling of many on the right in America.

Orbán told a cheering crowd of conference delegates that he and other conservatives were in a battle to protect Western civilization against the forces of liberalism and mass migration.

“If you separate Western civilization from its Judaeo-Christian heritage, the worst things in history happen," he said.

"Let’s be honest, the most evil things in modern history were carried out by people who hated Christianity. Don’t be afraid to call your enemies by their name. You can’t play safe but they will never show mercy.”

“Politics are not enough. This war is a culture war," he added.

Former President Donald Trump and his onetime chief strategist Steve Bannon are also speaking at CPAC, America’s top conservative conference. And both are fans of Orbán’s. Trump endorsed Orbán in January, three months before he was re-elected to a fourth term, and Bannon called the Hungarian leader “Trump before Trump” in a speech in Budapest in 2018.

While Trump was voted out, Orbán, the first European Union leader to speak out in support of Trump’s campaign in 2016, looks unassailable, with control over the media, the legislature and the judiciary in Hungary. Meanwhile, the fractured left-wing, centrist opposition is marginalized.

Fox News’ Tucker Carlson, who has interviewed Orbán and hosted his show from Budapest for a week in 2021, describes Hungary as a “small country with a lot of lessons for the rest of us.” In January Carlson released a documentary titled “Hungary vs. Soros: Fight for Civilization” — a reference to George Soros, 91, the Hungarian-born Jewish businessman and philanthropist who has become a scapegoat for Orbán and his allies.

One Hungarian writer, Balázs Gulyás, said that in praising Orbán, Carlson had depicted Hungary as a “conservative Disneyland.”

Ahead of this week’s conference, Trump released a picture of him and Orbán together. “Great spending time with my friend,” Trump said in a press release. “We discussed many interesting topics — few people know as much about what is going on in the world today. We were also celebrating his great electoral victory in April.”

‘21st century repression’

The effects of Orbán’s takeover are in many ways subtle, and Hungary does not outwardly appear to be an authoritarian state.

“Budapest is one of the most beautiful cities on Earth. It feels so functional and free — you get there and think ‘this can’t possibly be a dictatorship,’” says Kim Lane Scheppele, a sociologist at Princeton University and an expert on Hungarian politics.

“That’s because Orbán’s repression is a very 21st-century repression,” she said, adding that the country’s democracy had been eroded through changes to the Constitution, rather than through violence.

Freedom House, a Washington-based human rights advocacy group, rates Hungary as only a “partly free” country. In its rating for 2022, it said Orbán had used law changes to “consolidate control over the country’s independent institutions,” pass anti-immigrant and anti-LGBT+ policies and hinder opposition groups, journalists, universities and nongovernmental organizations.

In promotion of Orbán’s “family values” agenda, Hungary banned adoption by same-sex couples in 2020 and removed the right of transgender people to legally change gender. Hungary has also refused to ratify the Istanbul convention, a legally binding international agreement aimed at preventing violence against women signed by 34 European nations.

Republicans such as Sen. Ron Johnson, R-Wis., who said the Jan. 6 riot at the Capitol was largely a “peaceful protest,” have praised Orbán’s border policies. What exactly attracts the U.S. right to him?

“The reason that Orbán keeps winning is he has the control of a dictator,” Scheppele said. “So the question is, what are the Republicans in it for? Are they tilting away from the principle that the peaceful transfer of power is a bedrock of democracy, against the thought that whoever wins a majority should take power, the idea of separation of powers?

“How far do they want to go on this?” she added. “I think that’s the scary part.”

Bearded revolutionary

Viktor Mihály Orbán was born in 1963 in Székesfehérvár, about 40 miles west of Budapest. The family lived in modest surroundings. He says that as a boy, he and his siblings worked in the field feeding the pigs and chickens. He has also recounted that he first used a purpose-built bathroom and running hot water at the age of 15.

The Pancho Arena in the town of Felcsút was built in 2014 on the very field where the soccer-obsessed Orbán played as a youth. The handsome stadium has 3,800 seats, space for more than double the town’s population.

Orbán first made his name as a 26-year-old bearded revolutionary during the Communist government’s dying days. He was a recipient of a grant from George Soros’ Open Society Foundations to spend nine months at Oxford University to research civil society in European political philosophy.

Thirty-three years later, Orbán and his allies depict Soros as a dangerous puppetmaster behind Western plans to force migrants on unwilling countries. His Open Foundation funds independent groups working for justice, democratic governance and human rights, making him an obvious target for far-right nationalists.

In 2017 Fidesz ran an anti-immigration campaign that pictured Soros’ face with the slogan: “Let’s not let Soros have the last laugh.” Soros responded by calling the images “antisemitic” and part of a “deliberate disinformation campaign.”

A hybrid regime?

Paul Lendvai, 92, a journalist and biographer of Orbán, has a long acquaintance with opposition politics and power in his native Hungary. Born to Jewish parents, he was detained in a Hungarian internment camp before fleeing during the 1956 uprising against the Soviet-backed Communist government.

Speaking from his home in Vienna, Lendvai said that key to Orbán’s story is that Fidesz, which has won the last four elections with its coalition partners KDNP (the Christian Democratic People’s Party), controls all the major levers of power.

“At the moment it is a hybrid regime: an open dictatorship in between a cultural democracy with no possibility of changing the government because they have the majority to change the law, including electoral law. The courts are in their hands,” he said.

Lendvai’s 2017 biography “Orbán: Europe’s New Strongman” argues that Orbán’s control of all levers of government began with a new Constitution in 2011 that allowed major laws to be passed or changed only with a two-thirds “supermajority” in Parliament, which Orbán has had since 2010. That has led to crucial changes to the electoral system and media ownership rules.

“Hungary is no longer a democracy. It is not — or not yet — a dictatorship like Russia or China, people can demonstrate and travel to the West and set up [opposition] groups,” said Lendvai.

“But you can’t change anything because the entire communication industry, including so-called private and public, is in the hands of the government — 80% of the news.”

The press freedom group Reporters Without Borders said Orbán “has built a media empire whose outlets follow his party’s orders.”

In a lengthy response to questions posed by NBC News, the Hungarian government’s International Communications Office said that Fidesz-KDNP had received a record number of votes in April’s election, which it said was confirmed by independent observers. The government “is committed to ensure” rights such as a free and diverse media and free expression, it said, and has always “respected European values and has always conformed to rule of law expectations.”

“In Hungary there is zero tolerance” on racism and antisemitism, the statement said, adding: “such acts are to be punished with the full force of the law, and neither are they tolerated in political discourse.”

‘Only have to win once’

Orbán first made his name in 1989 at a funeral service to commemorate victims of the then-collapsing Communist regime, where he delivered a rousing speech on behalf of the younger generation in front of 250,000 people in Budapest’s Heroes’ Square.

Soros also supported the college where Orbán and many of his close associates studied, which became a launchpad for Fidesz — originally a left-of-center, youth-focused party that moved right during the 1990s.

But the shoots of liberal democracy did not flourish in the rubble of Hungary’s Communist government.

Orbán, who trained as a lawyer, became the youngest prime minister in Europe at the age of 35 in 1998 at the helm of a right-wing coalition, but was voted out in 2002 and lost again in 2006.

In 2009, he told a group of supporters: “We only have to win once, but then properly” — a statement widely interpreted to mean that measures could be taken to change the system for the party’s long-term benefit.

Today, Orbán has become a poster boy for hard-line autocratic elected leaders like Turkey’s Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro and Russia’s Putin. His transformation from the voice of Hungary’s youth to anti-immigrant nationalist leader appears to have culminated on July 25 when he declared during a speech: “This is why we have always fought: We are willing to mix with one another, but we do not want to become peoples of mixed-race.”

Orbán has refused to retract his comments but instead said they were misinterpreted.

‘Open exchange of ideas’

The American Conservative Union, the organizers of CPAC, defended their invitation to Orbán, regardless of his comments.

“CPAC is looking forward to hosting leaders from across the country and the world. We support the open exchange of ideas unlike so many American socialists. The press might despise Prime Minister Orbán, but he is a popular leader,” spokesman Alex Pfeiffer told NBC News.

Responding to the controversy, Matt Schlapp, CPAC chairman, said on Twitter,: “When we silence people we skip the chance to learn why [we] agree or disagree [with] their POV [point of view].”

European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen told a Slovakian newspaper on Saturday, in response to a question about Orbán’s comments: “All E.U. member states, including Hungary, signed up to common global values. … Discriminating on the basis of race is to trample on those values. The European Union is built on equality, tolerance, justice and fair play.”

The context of Orbán’s incendiary comments is Hungary’s mounting economic crisis, according to Péter Krekó, a fellow with the Center for European Policy Analysis in Budapest.

“Orbán is anything but stupid — he calculates that there will be domestic and international outrage,” he said.

“He has to explain to his voters why there will be a lot of economic difficulties despite having promised otherwise in the election campaign. He wants to fuel this simplified [debate] over immigration so he has to talk less about policy issues and explain why energy prices are going up.”

Krekó added: “It’s obvious this is not just classical, traditional nationalism. It goes way beyond that.”

Along with Poland, Hungary has long clashed with the E.U., which has given Budapest a matter of weeks to address concerns over the country’s rule of law breaches and restrictive anti-LGBT rules before it moves to suspend 21 billion euros ($21.4 billion) in funding.

These economic questions perhaps post Orbán’s greatest challenge yet.

“The question is how far [public] disappointment over the economic policy will go,” said Lendvai. “For the moment Hungary still does not ban demonstrations, or disperse them with force or tear gas. But if they get out of hand, Orbán will also take off the gloves.”

Lendvai is pessimistic about the possibility for political change, but adds as a parting note: “However, Hungarian history always contains surprises.”