Inside a Des Moines program hoping to reduce gun, youth violence in the city's north side

Driving down University Avenue in north Des Moines, Tim McCoy points to a small strip mall on his left, home of the Family Dollar and Mid-K Beauty Supply store. That's a "hot spot" for violent incidents, he says.

So many customers have stolen from Family Dollar that staff have posted a sign on the store's front doors that advises shoppers under the age of 16 to be accompanied by a parent or guardian, he explains. Mid-K has at least three to four employees walking around the store.

To onlookers, the mall appears ordinary — a bare brick building that rests on the edge of a busy street. Across from it is a health center that has long offered care for residents from underserved communities and people facing homelessness.

It can seem hard to imagine that beloved grandmother Barbara Perry was shot and killed seven years ago in that mall parking lot — the same lot that on an early September afternoon seemed quiet and nearly empty as McCoy showed the Des Moines Register around neighborhoods he canvasses as part of an effort to reduce youth violence in Iowa's capital city.

Over Labor Day weekend in 2016, Perry was struck in the head by a stray bullet while sitting in her vehicle parked in the Family Dollar lot — a homicide Des Moines police at the time compared to the death of Phyllis Davis in 1995. Davis was driving home from work when she was caught in the crossfire of a shooting between rival gangs and hit by a bullet, which killed her. Police also speculated Perry's death could have been gang-related.

McCoy says University Avenue divides the C-Block gang, who live in the Cheatom Park neighborhood, from its rival Strap Gang, who are scattered across the Evelyn K. Davis Park area. The strip mall falls in the middle of where the two territories meet — a victim in the crossfire.

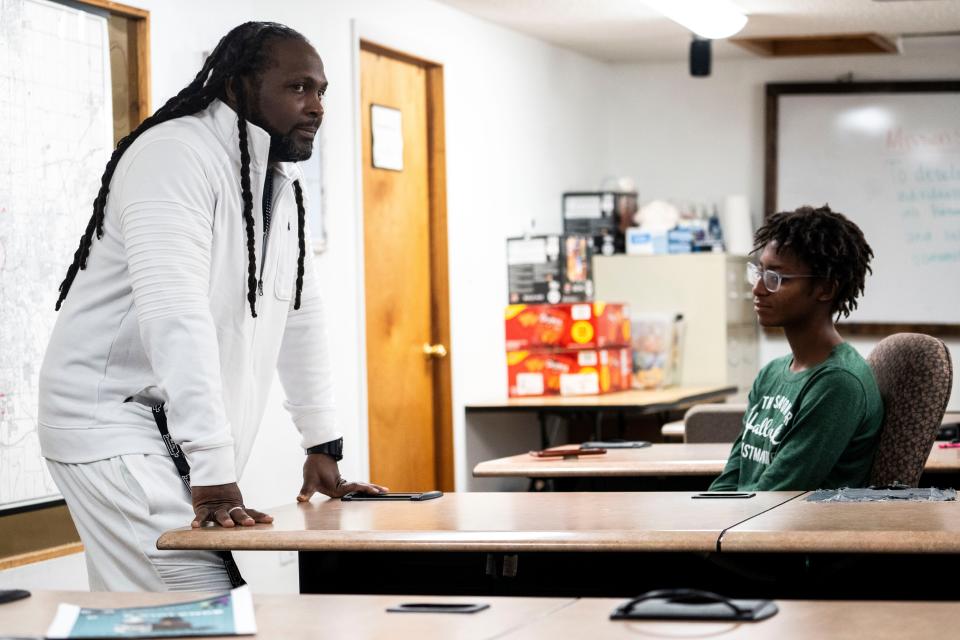

"I think that's why we experienced so much violence in front of that store," says McCoy, who in the last two years has overseen Creative Visions' Violence Interruption Project, a program that seeks to reduce gun violence and improve public safety in the city's north side neighborhoods.

McCoy is one of three community members — or "violence interrupters" — working to prevent, mediate and de-escalate conflicts among at-risk teens and young adults. The VIP team fosters relationships with youth, offering them resources, including a safe space and a listening ear.

In November, the Des Moines City Council approved another round of funding for the program, which Creative Visions organizers have pegged as a solution to combating gun and gang violence in the city's north side neighborhoods. And, they say, VIP, which is now entering its third year, may just be the missing piece that brings their services — and their communities — together.

What is the Violence Interruption Project?

Creative Visions launched VIP in December 2021 after City Council members moved forward with an initiative to reduce gun violence on the city's north side, using the Cure Violence model as a guide.

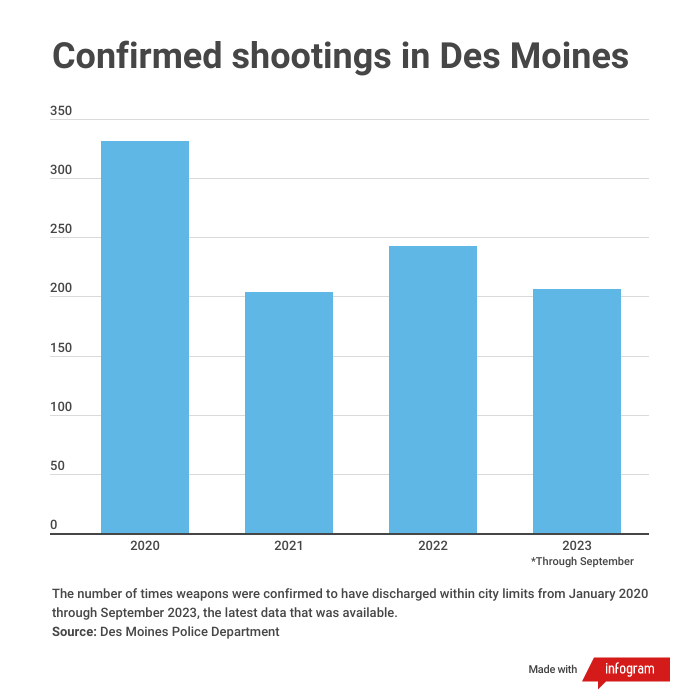

Des Moines in 2020 had one of its worst years for gun violence on record, with 331 shootings, according to data from the Des Moines Police Department. That same year, the police seized 690 firearms. A typical year sees an average of 246 shootings, police said.

The model, established by a nonprofit with the same name, first debuted on Chicago's West Side. It uses trained violence interrupters and outreach workers to identify and mediate conflicts within their communities. They work separately from police officers and closely with people at risk of participating in violent acts, helping them to understand "the cost" of their actions while connecting them to mental health services, job training or other resources.

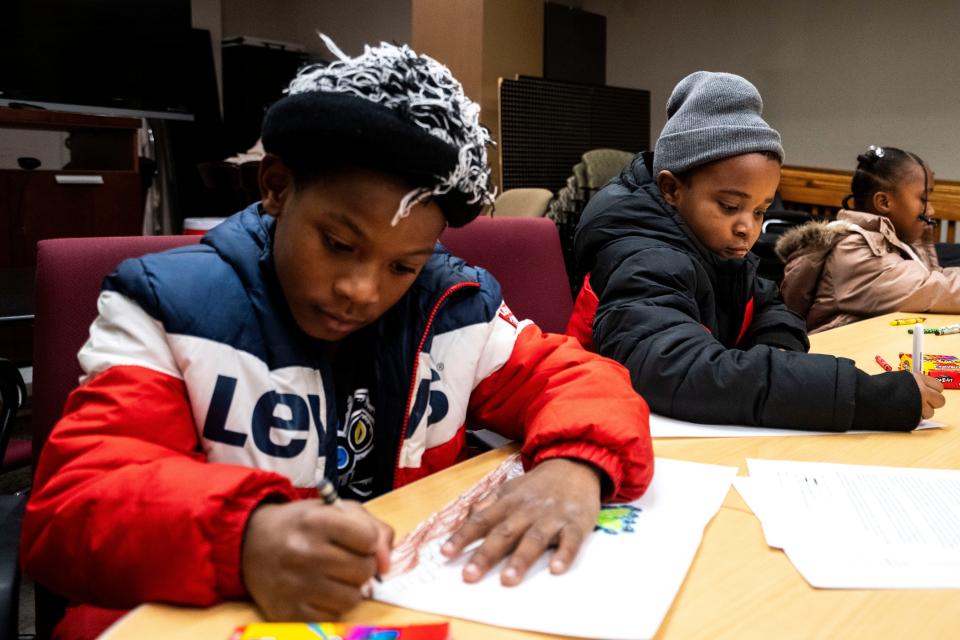

In Des Moines, the model was first proposed to target at-risk youth ages 14 to 25. But Ivette Muhammad, chief operating officer at Creative Visions, said VIP team members have seen that an increasing number of younger children are engaging in violence, with some as young as 10 or 11 years old.

Muhammad said it made sense to her that Creative Visions, which has long sat in the heart of the Evelyn K. Davis Park neighborhood, rolled out the VIP program because it aligns with Creative Visions' mission to keep Des Moines safe from violence. State Rep. Ako Abdul-Samad opened Creative Visions in 1996 as a response to Davis' death.

"We've been dealing with this for years" and have approached the issue by addressing the needs of the families the organization serves, Muhammad said. Over the years, Creative Visions has offered free food and clothes, employment resources, mentorship programs and after-school activities.

But, she says, the VIP program is the first violence-reduction effort at Creative Visions that has had a dedicated team and funding from the city. So far, Des Moines has invested $680,000 over two years to fund the program. Next year's contract is for $300,000.

That funding is a game-changer, allowing Creative Visions to hire violence interrupters, including McCoy and his two colleagues, Calvetta Harris and Victor Caldwell, and tailor VIP to meet the needs of north side communities that have experienced violence. City investment also brought more local leaders and community partners to the table, she said.

That means there are now more eyes on the problem, not just Creative Visions'.

"One entity can't boil the entire ocean," Muhammad said.

"You have real conversations among stakeholders to address real issues in the community, whereas before it was like an ostrich in the sand approach: If you don't see it, you don't address it, and it doesn't exist," she continued.

What does the Violence Interruption Project do?

The VIP team monitors four target zones — areas identified by Des Moines police that have high crime rates — mostly impacting the Drake and Evelyn K. Davis Park neighborhoods, as well as parts of River Bend and Mondamin Presidential.

Zones 1 and 2 include Second Avenue, 16th Street, Forest Avenue and Interstate 235. Zones 3 and 4 overlap them and also include Prospect Park, 27th Street and Hickman Road.

McCoy, Harris and Caldwell routinely canvass the catchment areas and work on-call shifts, responding to incidents that could turn violent and following up on those incidents to avert other acts.

Beyond that, the team has hosted community events for children and teens. The three regularly visit the Juvenile Detention Center and work with youth who are looking to return home and to their communities. They also deliver meals to residents in need in areas most prone to violent crimes and recruit "inroads," residents who share tips or information with VIP.

"The biggest point is to make ourselves available and in such a way where people don't look at it as abrasive," McCoy said. "At the end of the day, nobody really wants their neighborhood messed up — even if they don't know that they don't want that."

More: ‘A token of appreciation’: Over 20 volunteers in the metro to receive national recognition

Prevention measures crucial to helping youth stay out of trouble, police say

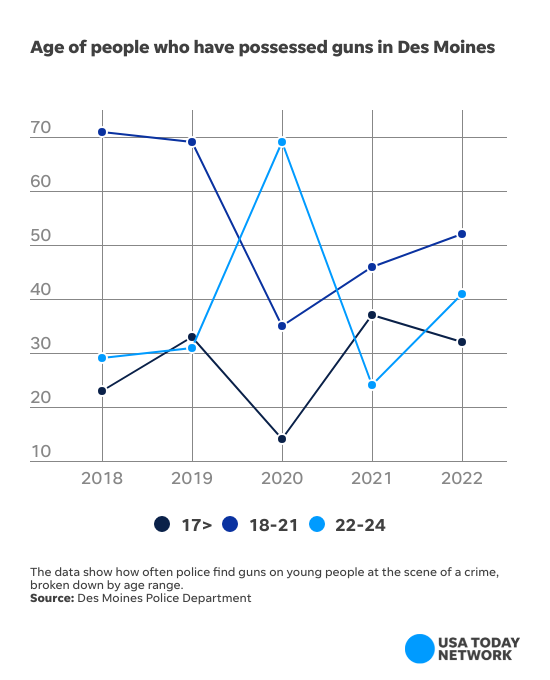

Sgt. Paul Parizek, spokesperson with the Des Moines Police Department, said the city has fewer gangs now than in the 1990s, but today's gang members skew much younger. They're also quicker "to be violent" and have more access to guns, he said.

Parizek said gangs make it easier for guns to land in the hands of children and teens. Gangs often purchase weapons and distribute them among younger people who in turn use them to handle disputes. The guns, he says, remain in circulation and change hands until police seize them.

In the last five years, the city has seen 84 homicide cases, police data obtained by the Register shows. Of those cases, 18 of the victims were age 18 and younger, Parizek said. And 29 of the suspects also were in the same age range.

Countywide, an average of roughly 679 youths faced criminal charges per year from 2012 to 2022, according to a public database from the Iowa Department of Human Rights' Criminal Justice and Juvenile Justice Planning.

Parizek told the Register a program like Creative Visions' VIP may help break that cycle as it strikes the balance between prevention and intervention.

"We're good at suppression. We're good at investigation," Parizek said of officers' roles. "Prevention? You know, we're not always there for that."

Parizek said the police department hosts youth sports programs and other events such as summer bike rides or Holidays with Heroes where local families shop for Christmas presents with officers. There's also a diversion program that supports youth, but Parizek argued that's not a prevention measure. Youths selected to participate in that program "are already in trouble," he said.

The department formed a gang unit in the late 1980s and up until a few years back had a program designated to intervene and suppress street crime. The city dismantled that program in 2020, Parizek says, following complaints that it targeted children of color.

Until there are more prevention measures to help youth, they will continue to fall in the cracks, Parizek said.

"Do we wave the victory flag when we send a 19-year-old to federal prison for 30 years? Is that a win? Not really," he said. "I mean, it's going to keep people safe now, but why can't we put the same amount of effort as a community into making sure he's not sitting in that courtroom?"

Police believe prevention starts at home and should include a partnership between schools and social service agencies.

"Now, that's where Ako (and Creative Visions) is filling a big void. And he's known (that) forever. Somebody needs to fill that void," Parizek said.

'Giving respect' key to building bridges, relationships, says violence interrupter

McCoy said some of the gang disputes go back 10 to 20 years ago — problems younger gang members have inherited from their predecessors. These "historical beefs," he opines, may be the reason why more children and teens are involved in violence today.

"Historical means that it's being talked about in the household among children, nieces, nephews, brothers, cousins," he explained. "That makes a difference to the mentality of individuals that are hearing it."

"A lot of time you ask some of the younger individuals: 'Why are you beefing?' And the only answer that they give you is because they're 'ops' (opposition)," he continued. "They don't really know what initiated."

On the drive with the Register, McCoy rattles off "hot spots" on his team's radar — including alleys, parks and apartment complexes. He talks about the "dope houses" that were purchased and renovated and the cul-de-sac where former C-Block gang members lived before police arrested them in 2019.

McCoy knows full well the lure and lore of gangs. There's power, control — and money. McCoy, who considers himself an inactive member of the 90 Crips, said he joined the gang partly to earn a living and sold crack cocaine to help his parents pay their bills and support his newborn son.

He was trying to follow in his older brother Raphael Robinson's footsteps. Robinson also was a member of the Crips.

But he says he sought to turn his life around after Robinson was brutally gunned down in 1996 — a case that remains unsolved and continues to hang over McCoy and his family.

"Creative Visions was one of the places that kept me from going crazy around that time," said McCoy who was 16 years old.

"He was my best friend/idol. We were almost inseparable to the point where people thought we were the same age," he said of Robinson, who was 26 when he died. "When he got killed, it hit me hard."

Those experiences drive McCoy to head VIP and approach the people with whom he works with sincerity, compassion and, importantly, respect.

"Perspective is a big factor. Just giving them respect is what gives me immunity," he said. "I'm not here to put them in jail, for one. And two, I don't judge them. I don't feel like I'm better than them."

Is Des Moines' Violence Interruption Project successful?

Violence intervention programs are not new initiatives, but studies measuring their success have been "mixed," said Ethan Rogers, an assistant research scientist at the University of Iowa's Public Policy Center. Researchers have cited too little staffing and funding as two key issues that have undermined the programs, he said.

"The most effective programs usually are led by one or two passionate workers who the community trusts, who the community has a strong relationship with — the community leans on," Rogers said. "Anytime a program relies on a single person, it's hard to keep them sustainable. It's hard to make sure that they're implemented evenly across multiple communities."

Two years in, Muhammad told the Register she and the VIP team have felt the strain of skeletal staffing and hope to expand the team and hire more interrupters. VIP reported last year that it faced language and cultural barriers while supporting families after the shooting outside of East High School that killed one teenager and seriously injured two others. It also recognized the need for more team members to be present in hospitals and courtrooms to help console families and mediate ongoing conflicts.

"When we're at the hospital, that's when people are mad," McCoy said. "Emotions are flying. People are not watching what's coming out of their mouths, so you can get a real take on what's about to happen."

Now, he explains, VIP can keep its eye on people, especially on those who make threats and say they may take action, and attempt to talk with them.

As for VIP's presence in the courtroom, McCoy says that's to help calm the tension between the families of victims and suspects. There, his team can hear "the whispers of what's about to happen."

"A lot of time people will go to court expecting a certain outcome," McCoy said. "And if they don't get that outcome … they're willing to shoot. They're willing to beat people. They're willing to jump people."

McCoy and Harris attended the hearings for Preston Walls and Bravon Tukes, two Des Moines friends who faced murder charges for the January shooting that killed two teens at Starts Right Here alternative school. April Wells of Creative Visions, who helps connect victims of violent crimes to resources, also accompanied the VIP team.

More: Teen-on-teen killings at Iowa nonprofit punctuate challenge of halting rising youth violence

The families can lean on VIP staffers and feel supported, Muhammad said.

Rogers said the most successful programs have relationships with other entities such as law enforcement, hospitals, businesses and schools.

Rogers said violence intervention programs face a challenge in determining how to measure their success rate, as methods and approaches can vary by catchment area. But there's always "promise" in programs that involve staff engaging with community members in meaningful ways, he said.

Creative Visions' VIP team members count the number of violent incidents they respond to, detailing the problem and participants involved, and nonfatal shootings in each of the target zones. In public reports, the participants' names are kept confidential, a way to maintain community trust, McCoy and Muhammad said.

A September report from Creative Visions showed that more than a month — 34 days — had passed since a nonfatal shooting in Zone 1 and about 2½ months — 74 days — in Zone 2.

Both Zone 3 and Zone 4 had not had any nonfatal shootings in the past year, the report stated.

The report also lists outcomes and resolutions, when reached. McCoy and Muhammad said they're working with an IT specialist to help collect better data, streamline their notes and track their progress.

City Manager Scott Sanders said he believes VIP has "brought a much-needed focus on youth violence" in the city and has "created positive momentum by de-escalating and redirecting potentially violent events."

Turning off University Avenue, McCoy weaves through quiet side streets. Soft R&B songs hum from the car stereo, filling pockets of silence between McCoy and Caldwell, who sat in the backseat.

McCoy jokingly calls himself a "we-sider," recalling spending his childhood shuffling from his parents' home on the west side to his grandmother's on the east side.

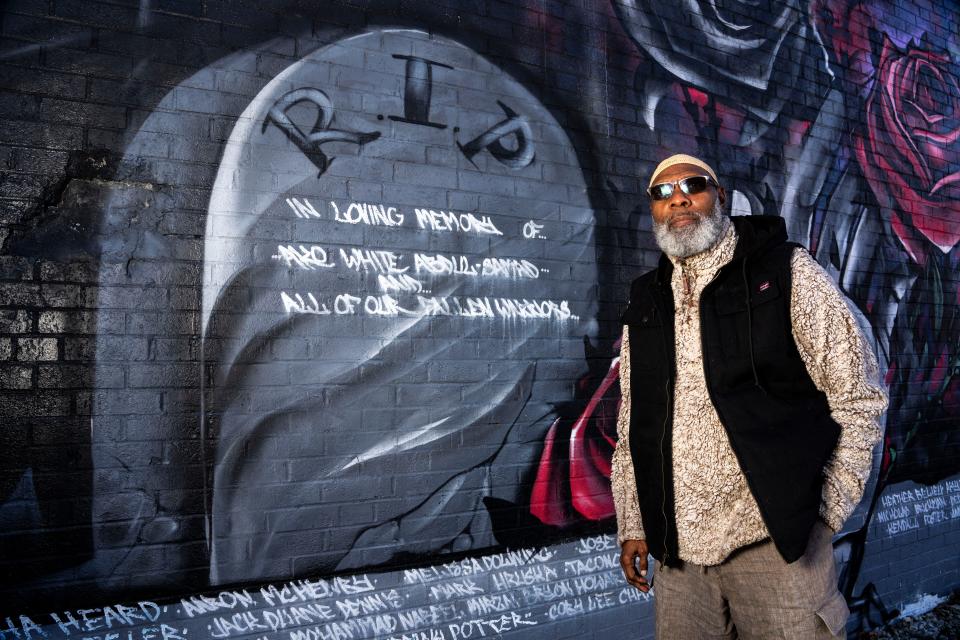

He says he thinks of Robinson often. His memory is kept alive on the mural that scales the wall of Creative Visions' building and through the VIP program – his name among the hundreds who died from violence.

Back on University Avenue, near Drake University, McCoy slows to find a parking space across from Lifestyle Juices. He and Caldwell often stop in to chat with the owner. The team has been working to strengthen its relationships with local business owners in the target zones, he said.

Of Lifestyle Juices, McCoy said he and Caldwell also have another incentive: They enjoy the fruit smoothies and juice shots.

Those are their vices now, he says, grabbing the cups from the counter and dashing back to the car, ready to pick up his daughter from school and head home.

F. Amanda Tugade covers social justice issues for the Des Moines Register. Email her at ftugade@dmreg.com or follow her on Twitter @writefelissa.

Noelle Alviz-Gransee is a breaking news reporter at the Des Moines Register. Follow her on Twitter@NoelleHannika or email her at NAlvizGransee@registermedia.com.

This article originally appeared on Des Moines Register: What is Des Moines' Creative Visions' Violence Interruption Project?