'Violence and widespread impunity': 2022 lining up as deadliest year for journalists in Mexico

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In Mexico, freedom of expression is a protected right under article 6 of the Constitution, and under article 7, the freedom to write and publish works on any subject, which includes freedom of the press, is also protected. However, day after day carrying out journalistic activity in Mexico becomes more of a risk.

So far in 2022, 16 journalists have been murdered, and every 14 hours at least one attack against journalists or a newsroom is reported, according to Pedro Cárdenas, protection coordinator at Article 19.

This situation has led the organization — which advocates for journalists' rights in Mexico and other Latin American countries — to consider 2022 as the deadliest year for the practice of journalism in Mexico if attacks against journalists continue at the same rate.

Article 19 is an independent, nonpartisan organization that promotes and defends freedom of expression and the right to information, and owes its name to article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which defends the rights to freedom of expression and opinion.

"In the first half of this year, 331 attacks were recorded. ... On average, every 14 hours they contacted us about attacks that we are documenting, which is quite critical," Cárdenas said in an interview with La Voz/The Arizona Republic.

“It is the deadliest year in terms of murders. In the first (half of 2022) we documented 12 murders of journalists, of which at least nine were due to their work (as journalists). No other semester has had this many murders, not one, at least as long as we've been counting. That does speak of a very high number of murders,” Cárdenas said.

Violence against Mexican press: 16 journalists have been killed in Mexico so far in 2022

Since 2000, Article 19 has documented 154 murders of journalists in Mexico — 142 men and 12 women, not including four recent murders reported in August.

"We are talking about at least 16 cases of murder so far this year, and if it continues like this, it will become the deadliest at the end of the year. Let's hope not, we are all waiting for change to prevent this from happening," Cárdenas said.

Among these cases, the most recent are those of Fredid Román Román, Juan Arjón López, Allan González and Ernesto Méndez — all murdered in August, in a different state and under different circumstances.

Méndez was shot and killed on Aug. 2 inside his family's bar in San Luis de La Paz, Guanajuato. He was the director of the news site Tu Voz. González was murdered during a series of attacks in Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua, on Aug. 11. He was the host of a show on the radio station Switch Mega. He was shot to death along with three others while they were broadcasting live for his radio show.

Arjón López's body was found on Aug. 16 along a highway near the municipality of San Luis Río Colorado, in the northern border state of Sonora. Ajrón López was the director of the news site "A qué le temes," which translates to "What are you afraid of?" Román Román was shot to death on Aug. 22 as he made his way from his office to his car in Chilpancingo, Guerrero. He was the founder and editor of the newspaper La Realidad.

Faced with this wave of lethal violence, and attacks and threats that are recorded daily, many have chosen to silence themselves or go into exile. Cases like that of Juan de Dios Davish García and his wife María de Jesús Peters, both journalists from Oaxaca, who were able to leave the country and relocate to Phoenix, Arizona, to protect their lives and their daughter's

In June, journalist Rodolfo Montes revealed that he was the target of several threats. He did it publicly, during one of President Andrés Manuel López Obrador's morning conferences — an event not dissimilar to the cry for help made by journalist Lourdes Maldonado. She was murdered in Tijuana, Baja California, on Jan. 23.

It was on July 20 that Montes demanded protection for himself and his loved ones after receiving threats from the Jalisco Nueva Generación drug cartel. López Obrador listened to him and promised to protect him with the protections granted under the Protection Mechanism for Human Rights Defenders and Journalists.

Montes told La Voz that while there has been a slow response from the government, the fear of being the next journalist on the list is still present.

Montes pleads president to help him, others under threat

Montes' case is one shared by many journalists — at least officially around 500 who are currently under the protection of the mechanism. The threats Montes said he received were made over the phone and extended to his daughter. He has been under the protection of the mechanism for some time, far before he asked López Obrador for protection during that morning meeting.

Montes is an independent journalist with three decades under his belt working in Quintana Roo for different local and national media.

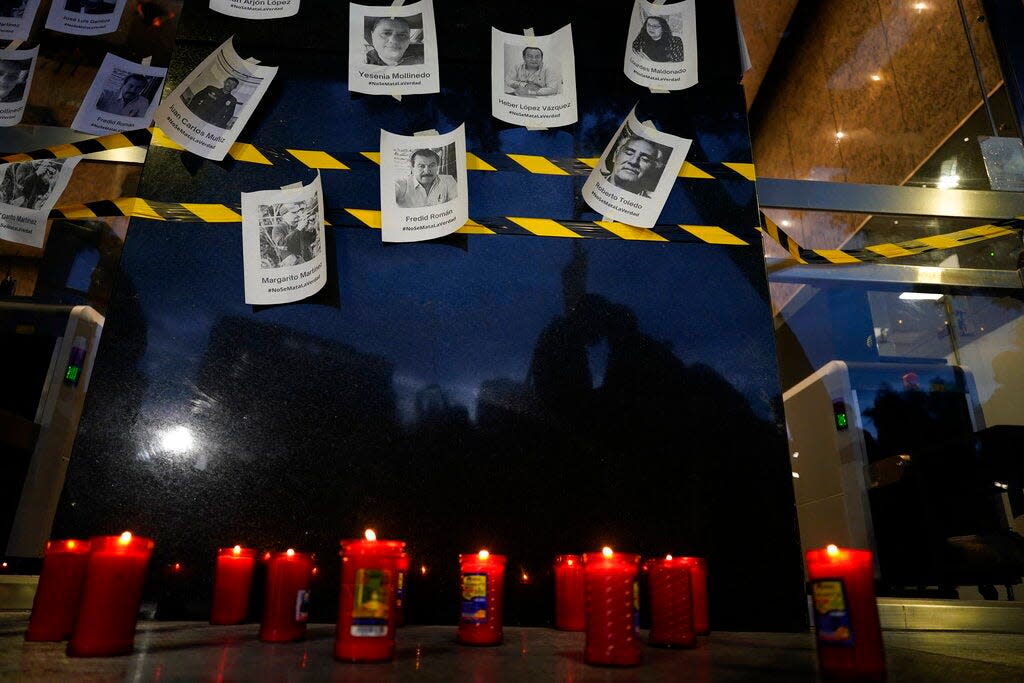

On Thursday, a group of journalists met at the gates of the Attorney General's Office in Mexico City, symbolically closing the Mexican office and demanding justice for their lost colleagues' loved ones.

Among them was Montes, who helped hang printed images of his colleagues.

Montes said that throughout his career he has received threats that have forced him to change homes, to register with the mechanism. In the most recent threat they were more direct and cruel, threatening his daughter, detailing that they were following her, informing him of her activities and how she was dressed that day, he said.

No longer satisfied with simply having a panic button to protect him from threat, he attended that morning meeting to demand change. Some protections came, but they have not been as helpful, he said.

“The mechanism is in a ball. ... The mechanism must change officials, because those who are there, are under suspicion in their actions, in their way of dealing with the emergency of a journalist,” he said.

The Protection Mechanism did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

The worst is not knowing, Montes said. Any moment could be your last.

“You don't live, you suffer. You go against the tide, you go with anxiety without knowing if one day you are going to return home because as soon as you leave you are going to be executed. That's how they've executed everyone," he said.

According to a report by Article 19, which details attacks against journalists during the first half of 2022 in Mexico, there are more attacks against journalists who cover corruption and politics beats. These are followed by security and justice beats, and human rights beats. Those who are most attacked are men as well as editorial directors of newsrooms.

A 'crisis of violence and impunity'

The mission of the Protection Mechanism for Human Rights Defenders and Journalists is to protect human rights defenders and journalists who suffer attacks as a result of their work. But both Cárdenas and other organizations consider that the mechanism is insufficient, since it has been overwhelmed by demands for protection.

The panic button that Montes carries is one of the protection measures offered by the program. Others include escorts, police patrols in their neighborhoods, change of homes, among others. Maldonado, a journalist murdered in Tijuana at the beginning of the year, was one of those protected under the mechanism. She also had a panic button on her person when she was killed.

“Our diagnosis — although the Protection Law of 2012 was created with the idea that there should be a protection process —: issues are not being worked on. They are not being fulfilled and (the government) ends up only focusing on a reactive process. 'I give you a panic button and that's it, our protection work is over,'" Cárdenas said.

Article 19 considers that the demand for protection of journalists has grown 10 times, compared to the previous year, and the mechanism, in response, has stagnated.

“There has been an enormous growth (in demands for protection), a mechanism that in 2012 served 100, 200 people now serves around 1,400 people. We are talking about enormous growth, with barely a quarter of the economic and personnel resources to serve them.

"The growth is not going at the same speed. That is, if we cover everyone, it is a disguised achievement because the personnel has not grown 10 times as much as the demand has grown," said Cárdenas.

Another issue that must be addressed, according to Cárdenas, is the lack of coordination and the lack of response to local and state authorities that carry out these tasks to protect journalists under threat.

“For example, the mechanism must make scheduled patrols every day, every week, but after two months of surveillance the state police no longer have gasoline, they no longer have a patrol vehicle, they can no longer do their rounds. Then the measures requested by the protection mechanism are broken,” Cárdenas said.

Jan-Albert Hootsen, representative in Mexico of the Committee to Protect Journalists, said that Mexico is in a crisis of violence and impunity.

“It is the most violent year in general for the population — for women, for human rights defenders, for immigrants — the list is endless. Mexico, at this moment, is in a crisis of violence and widespread impunity.

"And as has happened with other governments, the government of Andrés Manuel López Obrador has not been very effective in dealing with this problem. We continue to hope that there will be a change of course. It is urgent," he said.

The murders against journalists so far in 2022, according to Jan-Albert, are the result of the impunity that exists in Mexico.

“I believe that what we have seen in recent months is the tragic, but also very logical, consequence of the negligence of many years, on the part of the Mexican government at all levels, in the fight against corruption, in the fight against to impunity, to the contempt that the Mexican State has also shown to the freedom of the press," Hootsen said.

Diana García is La Voz's correspondent in Mexico City. Follow her on Twitter @dianagaav.

Support local journalism. Subscribe to azcentral.com today.

This article originally appeared on Arizona Republic: Journalists are being murdered in Mexico; activists demand justice