Virginia bill targeting critical race theory cites wrong Lincoln debate

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

CORRECTION: An earlier version misstated when Delegate Wren Williams took office. Williams took office on Wednesday.

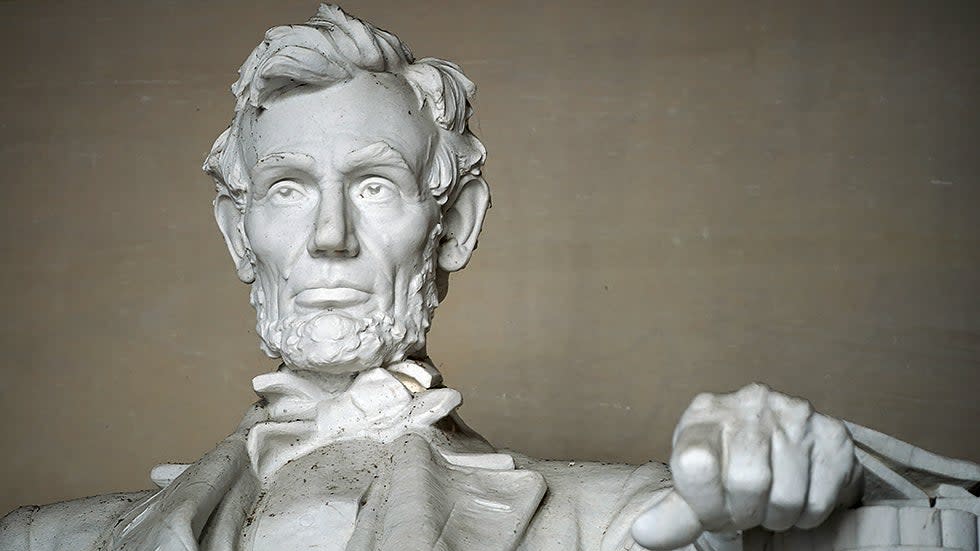

A new measure aimed at eliminating critical race theory in Virginia schools proposes teaching students about key documents in American history - including a debate between President Abraham Lincoln and the abolitionist Frederick Douglass that never happened.

The bill, introduced this week by freshman Delegate Wren Williams (R), appears to confuse Frederick Douglass with Sen. Stephen Douglas (D), who battled Lincoln for a seat in the Senate in 1858.

It requires schools to provide students with an understanding of America's founding documents, including the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution and the Federalist Papers.

It also says that Virginia students should also be able to demonstrate knowledge of Alexis de Tocqueville's "Democracy in America," the writings of the Founding Fathers, and "the first debate between Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass."

The only problem is that Lincoln and Douglass never debated. Lincoln debated Sen. Stephen Douglas (D).

In a statement Friday, the Division of Legislative Services, the nonpartisan agency that drafts bills for lawmakers, took responsibility for the error.

"The erroneous citation of Frederick Douglass, in relation to the Lincoln-Douglas debates between Abraham Lincoln and Stephen Douglas, was inserted at the drafting level, following receipt of a historically accurate request from the office of Delegate Wren Williams," the DLS said in the unsigned statement.

Frederick Douglass was nowhere near Illinois at the time Lincoln and Sen. Douglas barnstormed the state. Born into slavery in Maryland, he had escaped to free Massachusetts in 1838, where he became a preacher and a prominent abolitionist. By the time Lincoln and Stephen Douglas were debating, Frederick Douglass had moved to Rochester, N.Y., where he conferred with John Brown, the abolitionist who later took over an arsenal at Harpers Ferry, W.Va.

Lincoln, a member of the relatively new Republican Party who had served one term in Congress a decade earlier, and Stephen Douglas, a Democrat who had helped broker the Compromise of 1850, used joint appearances in each of Illinois's nine congressional districts to stump for their party's candidates for the state legislature. Those legislators would eventually elect a senator.

Their first debate, in Ottawa on August 21, was indeed an historical moment. Lincoln deplored the "monstrous injustice of slavery," and castigated those who were indifferent to the debate over abolition. Douglas responded by criticizing Lincoln's opposition to the Supreme Court's decision in Dred Scott v. Sandford, decided the previous year, which held that the Constitution did not convey citizenship to people of African descent, whether they were free or slaves.

Stephen Douglas won the race for a Senate seat. Lincoln went on to beat Douglas in the race for the White House two years later.

Lincoln and Frederick Douglass did meet, but not until five years later, when Lincoln was in the White House and Frederick Douglass was recruiting Black soldiers for the Union Army in the midst of the Civil War. In that meeting, Douglass told Lincoln that Black soldiers should receive the same pay as whites, and that the Union should demand the same protections for Black soldiers taken captive by the Confederate Army as they did whites.

Lincoln did not commit to paying Blacks the same as whites, but he left an impression on Douglass nonetheless.

"Though I was not entirely satisfied with his views, I was so well satisfied with the man and with the educating tendency of the conflict that I determined to go on with the recruiting" of Black soldiers, Douglass later wrote.

Lincoln invited Douglass to the White House three more times. It is not clear whether he ever invited Stephen Douglas to the White House.

Williams, who represents a district on Virginia's southern border with North Carolina, took office this week.

The Virginia bill was meant to keep "divisive concepts" out of school curricula, including teaching that the Commonwealth of Virginia or the United States as a whole are "fundamentally or systematically racist or sexist."

It requires the state Board of Education to teach the "fundamental moral, political, and intellectual foundations of the American experiment in self government."

This story was updated at 4:31 p.m.