Virginia governor's rollback of rights restoration has disenfranchised thousands of voters

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Shawn Barksdale lost his right to vote before he was even old enough to cast a ballot.

When he was 17 years old and living in South Boston, Virginia, Barksdale was convicted of a felony in 1994 for selling cocaine and sentenced to Barrett Juvenile Correction Center for one year.

“I ran in the streets,” he said. “I turned 18 inside of that juvenile system.”

Barksdale, now 47, said that losing the right to vote at such a young age made him angry and without a voice.

“My mindset was, ‘My vote doesn’t count anyway,’” he said. “I really didn’t understand the right, the power of voting.”

That disenfranchisement, in part, led to another prison sentence, this time 15 years for armed robbery for Barksdale when he was in his early 20s.

At the time of Barksdale’s first felony conviction, restoring the right to vote for a formerly incarcerated person was a power only the governor had. That’s thanks to an article in the commonwealth’s constitution dating back to the beginning of the 19th century.

In the last ten years, Virginia’s governors have used that constitutional authority to lock the gate, allow entry to only a chosen few, or throw the gate wide open.

That centuries-old clause is now the focus of a bipartisan push for change that could affect tens of thousands of citizens’ ability to vote.

What’s a governor to do?

Article II Section I of the Constitution reads: “No person who has been convicted of a felony shall be qualified to vote unless his civil rights have been restored by the Governor or other appropriate authority.”

Experts have noted that the clause is a relic of Virginia’s pre-Civil War era. It first appeared in the 1830 version of the commonwealth’s constitution, A.E. Dick Howard, a law professor at the University of Virginia and constitutional scholar, said. Virginia’s constitution had been overhauled a handful of times since, with the most recent document restructuring in 1971. Howard was one of the architects of that 1971 document.

“There’s no doubt that [the 1830 clause] operates today, heavily and disproportionately, to disenfranchise Black citizens,” Howard said. “This, to me, is one of the most important public policy issues in Virginia today. I think the constitutional provision ought to be taken out, it ought to be amended. Restoring the vote ought to be automatic,” he said.

Over the last ten years, three out of four governors have attempted to work within the confines of the existing constitution to restore the right to vote to as many people as possible.

In 2013, then-Republican Governor Bob McDonnell made the first significant change regarding rights restoration. He streamlined the process and eliminated the two years non-violent offenders must wait before having their voting rights restored through an executive action.

In 2016, then-Democratic Governor Terry McAuliffe issued an executive order that restored voting rights to any Virginian with a felony conviction who had fulfilled the terms of their incarceration and supervised release. The Virginia Supreme Court ruled, however, that McAuliffe’s order was unconstitutional later that year. Under the Virginia constitution, McAuliffe was required to determine whether a returning citizen would be allowed to vote on a case-by-case basis.

In 2021, then-Democratic Governor Ralph Northam took executive action to automatically restore the right to vote to all Virginians who were not incarcerated, according to the Brennen Center for Justice.

At the start of his term, Republican Governor Glenn Youngkin maintained Northam’s approach. After automatically restoring the rights of a few thousand returning citizens, Youngkin rolled back that practice and now requires each returning citizen to apply to have their rights restored.

Thousands withheld from voting under Youngkin

There were 22,088 people released from prison who served one year or longer for felony convictions between fiscal year 2022 and 2023, according to data provided by the Virginia Department of Corrections.

In 2022, Youngkin restored the voting rights of about 4,000 people. That data is not yet available for 2023.

Shawn Weneta, a policy strategist with the ACLU of Virginia, estimated that there are now 25,000 Virginians who have not been able to vote in the two years since Youngkin rolled back automatic voter restoration. Determining precisely how many people are waiting to have their voting rights restored is challenging.

“We don’t know how many people are affected by the current requirements because it’s unclear what the current requirements are,” said Tram Nguyen, co-executive director of the New Virginia Majority. She has been working on efforts to get automatic restoration of voting rights codified in the Virginia constitution since 2009.

“We don’t want to have to fight this, administration after administration, every four years – it can get really confusing for folks,” she said.

With a new amendment filed for the 2024 session and slated to be brought to the floor for a vote in 2025, advocates hope to send a referendum to the voters by 2026. They hope the amendment will alleviate confusion faced by many returning citizens as they attempt to navigate the changing system. And the amendment will take the power out of the governor’s hands.

Del. Elizabeth Bennett-Parker, D – Alexandria, chief patron of the latest constitutional amendment, said that the current system disproportionately affects Black communities. Virginia currently disenfranchises twice as many black voters as other states, or more than one in seven Black Virginians, she said.

That included Barksdale, who was released from prison in early 2016 but did not regain his right to vote until 2018. He has advocated for the automatic restoration of rights to returning citizens because of his intimate knowledge of the system.

From incarceration to rights advocacy

Barksdale sat at a card table covered with a burgundy tablecloth at the back of the meeting room in St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in downtown Richmond, steps away from the Virginia capitol building. He was prepared to join Weneta to lobby lawmakers on a cold and wet January morning in the second week of the 2024 legislative session. Dozens of advocates had gathered in the church to rally and plan their morning. Then, they broke into groups to meet with dozens of lawmakers within a few hours to discuss criminal justice reform.

In 2018, a few months after he finished his parole and applied, Barksdale received a manila envelope from Northam’s office. Inside was a piece of paper outlining his rights that had been restored, stamped with the official seal of the governor’s office.

“That feeling and seeing that gold seal, I knew that my voice would make a difference,” he said. “Gaining that right, I said, ‘How can I empower others?’”

Now a motivational speaker, entrepreneur, and advocate for the restoration of rights for formerly incarcerated people, Barksdale has partnered with different organizations, including the League of Women Voters, to educate people on the importance of voting access for all.

His and other advocates’ efforts have become critical in the last two years because of Youngkin’s rollback of automatic restoration of rights.

The rollback of automatic restoration

When Youngkin entered office, he first maintained the same automatic restoration as Northam. After restoring rights to thousands of people at the start of his term, he quietly rolled back automatic restoration.

“All of a sudden, we got calls in the League [of Women Voters], our phone was ringing off the hook in the office,” Denise Harrington, advocacy director for the League of Women Voters Virginia, said.

The policy change made Virginia the only state in the nation that permanently disenfranchises all people with felony convictions, unless the governor’s office approves individual rights restoration, according to the Brennan Center for Justice.

The state government’s website that people accessed to see if their rights had been restored was changed to require an application, said Harrington. Now, all returning citizens must fill out an application, complete all probation or parole, and pay all restitution. The governor’s office then reviews each application on a case-by-case basis.

But that process lacks transparency, according to the Virginia State Conference of the NAACP. The Virginia NAACP filed a lawsuit against the Youngkin administration in July to obtain details on the process.

Speaker of the House of Delegates Don Scott, whose rights were restored by McDonnell in 2013 after serving time for a drug-related conviction, said Youngkin’s actions took away people’s dignity and their right to participate in democracy. The Democrat noted that more transparency is needed.

“We don’t know how he makes the decisions,” he said. On January 10, 2024, Scott became the first Black Speaker of the House of Delegates in Virginia's history.

Youngkin spokesperson Christian Martinez said the governor has committed to increasing the efficiency and transparency of the restoration of rights process for applicants. Martinez noted that applications are assessed on an individual basis according to the law and consideration of the unique elements of each situation, consistent with the 2016 Virginia Supreme Court decision.

He did not respond when asked if that commitment to transparency was new and the direct result of the court case brought by the Virginia NAACP.

“Our philosophy has been ‘Let the people decide,’” Harrington said. “Let people have a referendum on it so that we’re not having this outdated model where you have to grovel in front of the governor to get your rights back.”

The effort to amend Virginia’s constitution has garnered bipartisan support. Republicans have authored companion bills to automatically restore voting rights in the 2022 session.

Northam’s order and a stalled amendment

Weneta led a group of volunteers out of St. Paul’s – the same church that welcomed him back into society three years ago – and into the new General Assembly Building. Weneta had his rights restored after receiving a pardon from Northam. He had been convicted of embezzlement and served 16 years. He was released from prison in 2020.

“After I came home, I still couldn’t vote. I owned a business, I employed four people, I was paying taxes, and I still couldn’t cast a vote,” he said.

About a year after Weneta’s release, Northam signed his executive order to restore voting rights automatically to all returning citizens. At an event in March 2021 to mark the occasion, Northam sat down at a table and signed Weneta’s restoration order in front of him.

“I still have the pen,” Weneta said. Northam restored the right to vote to nearly 70,000 people that day.

Around that time, Weneta was a legislative liaison with The Humanization Project. He helped to get the first reference of a constitutional amendment to restore voting rights passed in the General Assembly in 2021.

Initially written to support universal suffrage – to allow anyone of age to vote whether they’re incarcerated or not – that bill was amended in the Senate to restore voting rights to people who have returned from incarceration. Nearly to the finish line, the bill died in the House during its second reference in 2022.

Empowering the next generation of voters

Barksdale began to educate himself on the importance of voting while in prison.

“I went from saying, ‘Oh, my vote doesn’t count,’ to thinking, ‘Hey, why would they, out of everything they could have taken, they took this from me,’” he said. “I started to really educate myself on the constitution.”

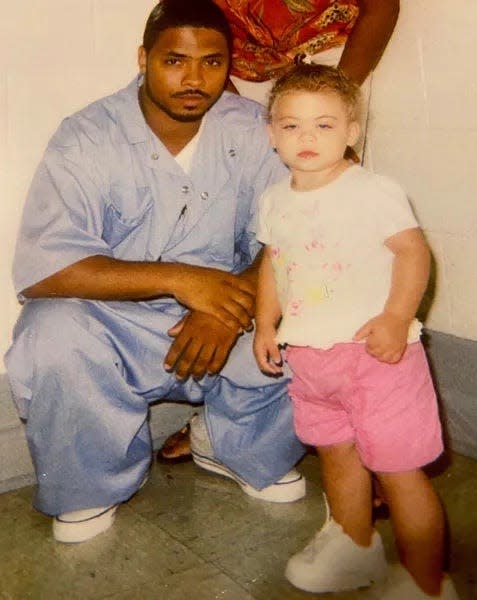

Though he was incarcerated for most of his daughter’s life, Barksdale worked to instill knowledge about the power of voting in her during monthly visits. He would talk with her about the importance of having and exercising that right.

Barksdale was 44 years old the first time he cast a ballot in the 2020 election. He and his then-18-year-old daughter voted for the first time together that year.

“We understand the significance and the importance of having that civil right – to be able to vote,” he said. “That is why it was so monumental when we voted together.”

This article originally appeared on Staunton News Leader: Virginia governor push limits thousands of voters, advocates say