I visited the classroom where my son was killed 5 years ago. It's still there — for now

In 2018, a 19-year-old former student shot and killed 17 people inside Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, in under four minutes. The shooter pled guilty and was sentenced to multiple life sentences in prison. Now the site of the shooting, the 1200 building on the school's campus, is scheduled to be demolished, but not before survivors and victims' families have a chance to walk through the building.

Warning: This post contains graphic descriptions of a school shooting.

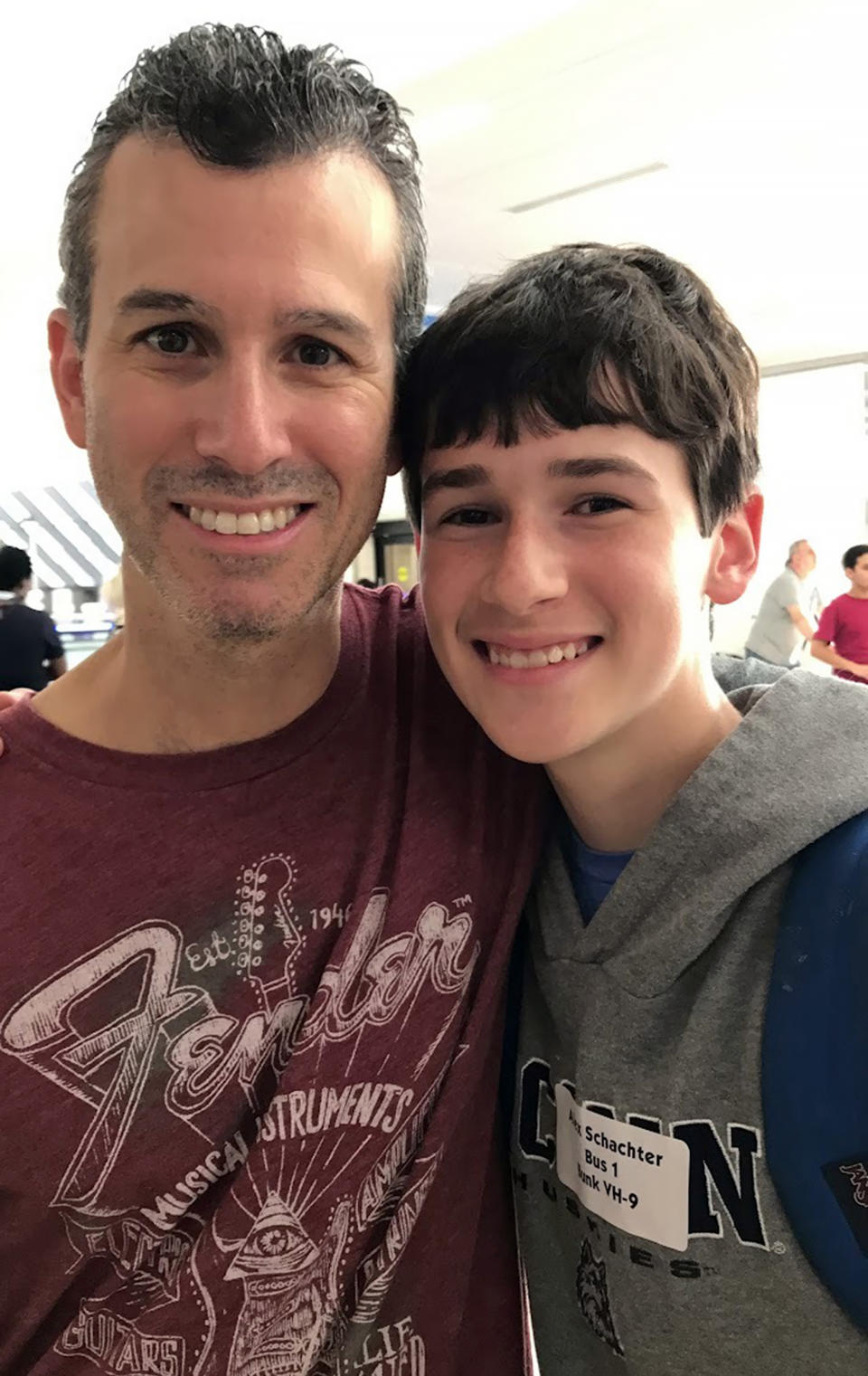

Feb. 14, 2018, was the last day I saw my son Alex Schachter alive.

"I love you, have a great day in school," were the last words I said to him.

It didn't occur to me that he could be murdered in his English class.

Later that day, a 19-year-old armed with an AR-15 entered my son's school, Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School, and killed 17 people.

My forever 14-year-old Alex was one of them.

In the years since the shooting, the building was basically hermetically sealed off from the other buildings on campus — a perfectly preserved crime scene where only the bodies of the deceased were removed.

During the shooter's trial, the jury was led through the school — story by story, class by class — along the same route the shooter took as he hunted his victims.

At that time, I had never contemplated the possibility of one day visiting the school myself. Some of the surviving families wanted to know everything — to see the horrific crime scene photos and read the devastating autopsy reports.

I did not.

In 2008, my then-wife passed away. I found her in bed one morning and couldn't wake her up. I thought that was the worst moment of my life, so after seeing her I promised myself I would never do that again.

I didn't identify Alex's body; I asked the kind people at the Star of David Funeral Home to do that for me. There were pictures I refused to see and places I would not let my brain go. It was just too painful.

Then I was given the opportunity to visit the school before it will be demolished, and something inside me shifted.

I desperately needed to stand in the spot where my son took his last breath.

I wanted to connect with Alex. I wanted to sit in the very chair he was sitting in when he was shot. I wanted to know exactly what happened, exactly how he died and to maybe, just maybe, have all my lingering questions answered.

The morning of Thursday, July 6, ahead of my visit, I re-watched the prosecution's closing arguments of the murder trial. Attorney Michael "Mike" Satz was methodical, taking us room by room and shot by shot.

I also re-watched the medical examiner's testimony of Alex's injuries. I had heard it that day, in the courtroom, but I couldn't process it. Instead, I was crying so uncontrollably that the defense tried to declare a mistrial.

After the videos, I put on my Alex T-shirt, my "Safe Schools For Alex" hat and my jacket — I knew my always thoughtful boy Alex would want me to wear a jacket — and drove to the school.

My family members and friends were concerned. I fielded phone calls from my wife, my three surviving children, my father and dear friends who volunteered to go with me.

I knew the visit was something I had to do, and I knew I had to do it alone. I simply did not want to burden anyone else with the horror I was about to see.

I parked at the school and walked into the gym. I was greeted by the victims advocates and the entire prosecutorial team, all sitting and waiting for me.

As I prepared to begin my walk-through, Debbie Hixon, who lost her husband Chris Hixon in the shooting, was finishing hers.

Debbie and I embraced, talked for a few minutes and then I went into the first hallway the shooter entered on that fateful day.

There was broken glass everywhere. Mike, the prosecutor, began describing the murderer's path, including where he took his first shots.

I saw the spot where Gina Montalto was shot and killed. She was sitting outside her classroom because she wanted a quiet space to work.

Luke Hoyer and Martin Duque were near her, returning to their class after running an errand. They were knocking on their classroom door when they were shot and killed — all described to me as it was during the murder trial.

Then Mike took me into Alex's room. I wasn't prepared for what I saw.

There was blood everywhere. Some part of my mind — the part, perhaps, that has been working so hard for the past five years to protect the shattered pieces of my heart — thought the blood would have evaporated somehow.

But Alex's chair was covered in his blood. In my baby's blood.

Mike then told me, step-by-step, what happened to Alex.

Alex must have heard the shots from the hallway. He had stood up from his desk when the murderer shot him through the classroom door window, striking my son twice in the chest. His spinal cord was severed and he died instantly.

My son had been sitting with three other kids. All four were shot.

The shooter returned to Alex's classroom after firing into the hallway. It was then that he shot and killed my son's classmates, Alaina Petty and Alyssa Alhadeff, while they were hiding.

An English paper Alex had been working on still laid on the floor near his desk. As I went down to pick it up someone asked if I wanted gloves because it had Alex's blood on it.

"No, I don't care," I responded. "It's my little boy's blood."

I then gathered the rest of my son's papers and his English book, still underneath his desk, to take home.

I couldn't bring myself to sit in Alex's chair. There was just too much blood on it. I have requested that I be allowed to take it home.

It's unbelievable, the carnage inflicted in a matter of minutes. As I walked through the rest of the school where 17 people were killed and 17 others wounded, I felt sick.

I was also angry.

Since my son's murder, I have dedicated my life to ensuring schools are safer for our children. Twenty-three days after the shooting, I helped pass the Stoneman Douglas High School Public Safety Act in Florida, and schools are safer as a result.

With Alex on my shoulder, I joined the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School Public Safety Commission. The Luke and Alex School Safety Act was included in the 2022 Bipartisan Safer Communities Act.

I helped create SchoolSafety.gov, the federal school safety clearinghouse working to make schools a safe place to learn nationwide.

I also created a charity, Safe Schools for Alex. I have no plan of slowing down.

After seeing the spot where my son was murdered, now more than ever I am convinced that every elected leader needs to walk through the crime scenes of mass shootings in their communities. Those in power must come down from their ivory towers to understand the implications of not prioritizing safety and security above all else.

And I must continue to explain to people that safety must come before education, because you can't teach dead kids.

My son was a funny kid who loved to watch football and basketball. He was a talented musician who loved music from the '70s — his favorite song was Chicago's "25 or 6 to 4."

Alex was also an adoring big brother, who would let his little sister comb his hair while he played video games, and who loved his older brother and sister so much.

He should be here. He should be a thriving 20-year-old.

I know he was scared. He stood up to try and escape the gunfire but he didn't have the time.

I hope and pray he didn't suffer.

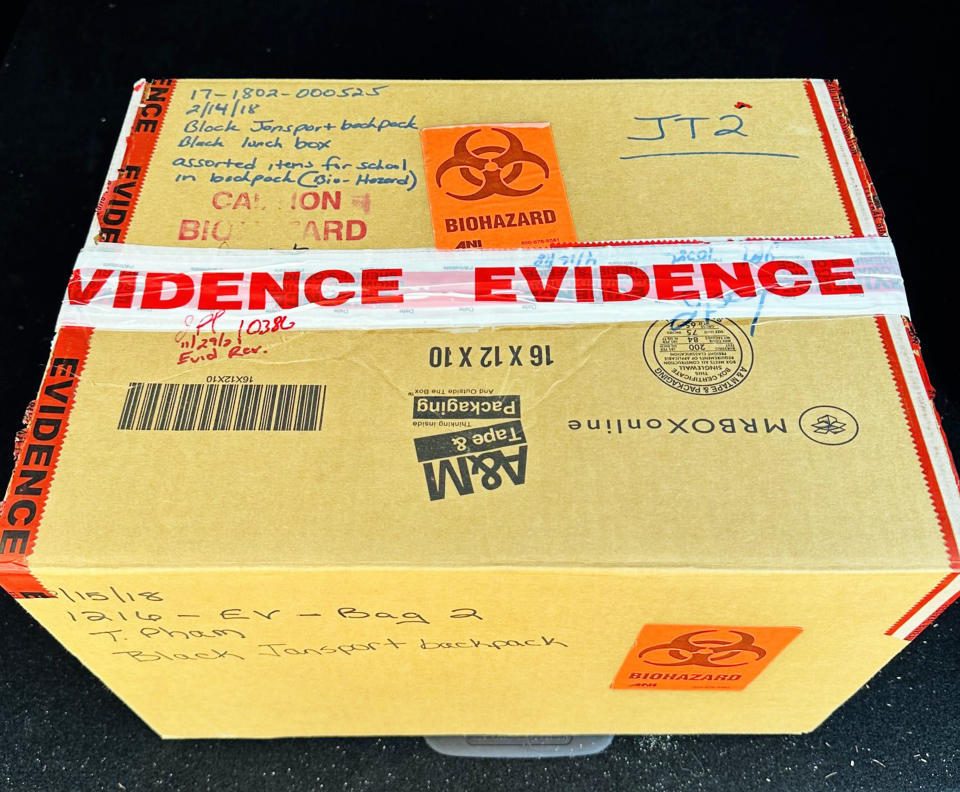

Days after I stood in the spot where my son took his last breath, I received two additional items that belonged to Alex. In a box labeled "evidence" and "biohazard" was Alex's book bag and lunch box. I was told it's a "biohazard" because it has my son's blood on it and potentially has bullet holes.

I can't bring myself to open it.

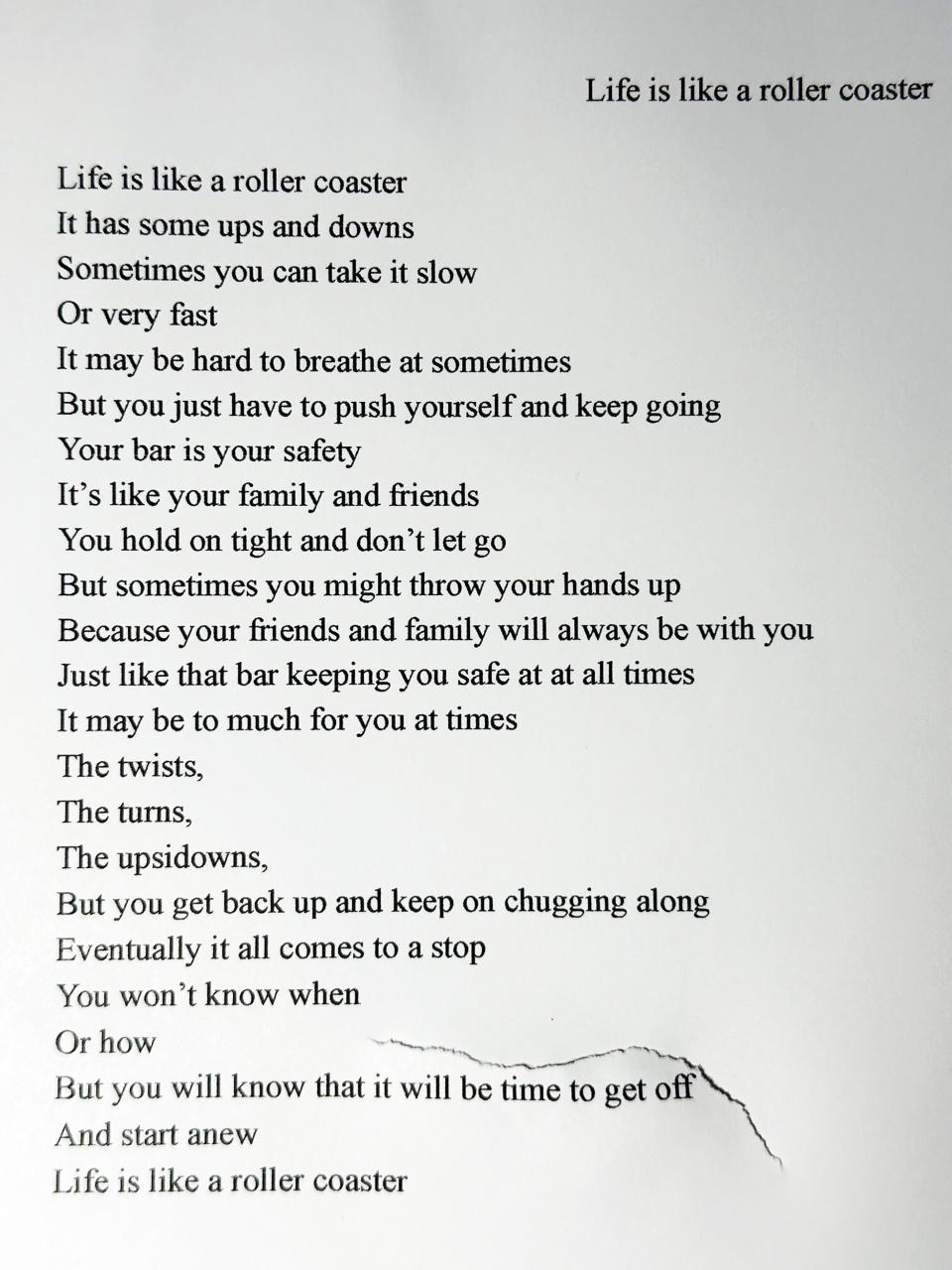

I also received the final draft of a poem Alex turned into his teacher before he was murdered. It's titled "Life is Like a Roller Coaster." My son, Ryan, found a crumpled up rough draft of the same poem in Alex's wastebasket the night before his funeral.

His final poem was pierced by a bullet.

As told to Danielle Campoamor

This article was originally published on TODAY.com