Visiting Our Past: Decent WNC people caught up in indecency

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Secrets were secrets for a reason," Celia Szapka thought as she boarded a train for Oak Ridge, Tenn., in 1943.

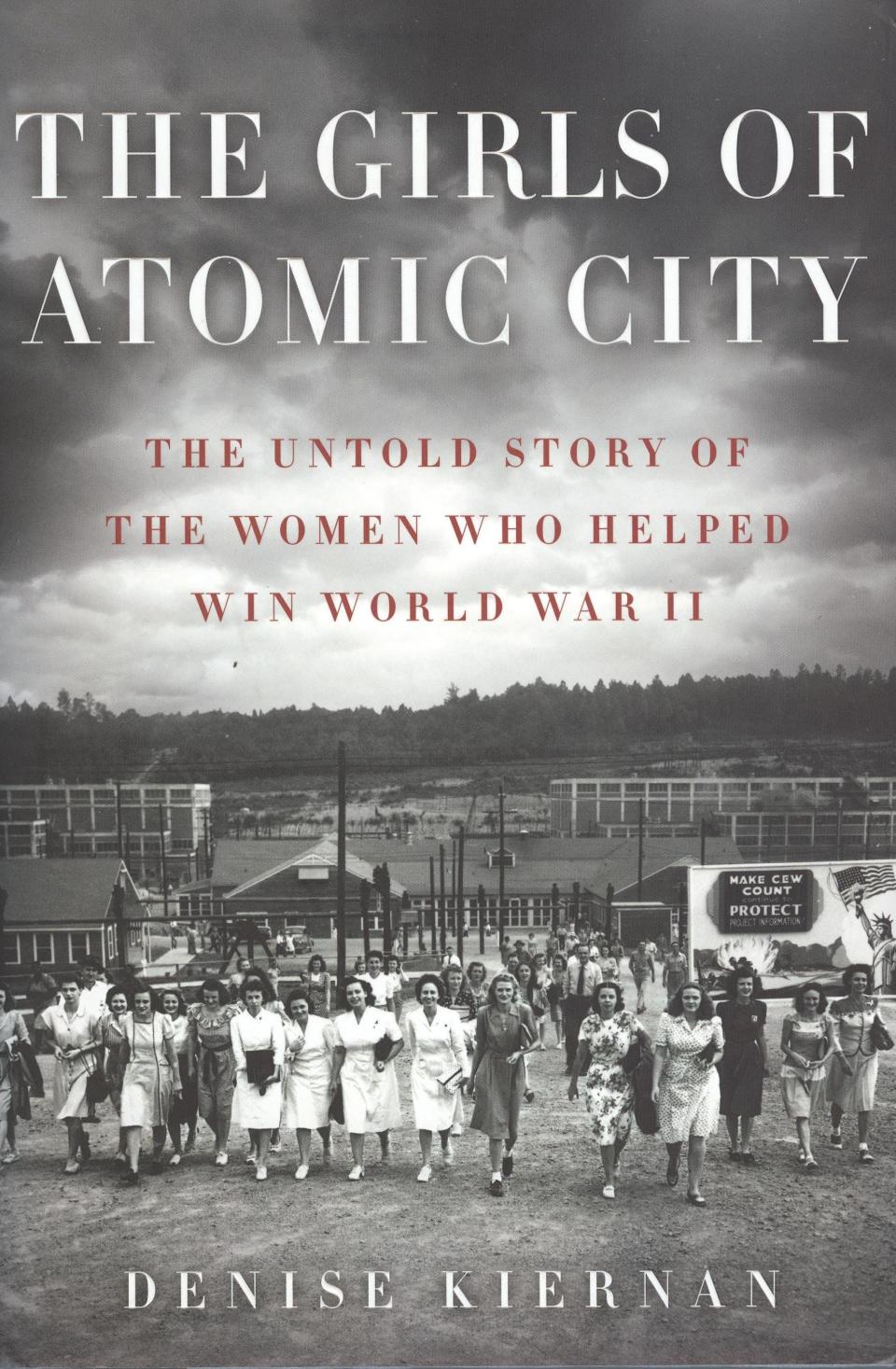

In her book, "The Girls of Atomic City: The Untold Story of the Women Who Helped Win World War II," Denise Kiernan follows the life-changing paths, exhilarations and regrets of nine young women who unknowingly helped build the bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

"If there was a need for her to know something critical," Kiernan says about Szapka's state of mind, "she would be told when the time was right."

After the Aug. 6, 1945 bombing of Hiroshima, the world as well as Oak Ridge families learned the secret of Oak Ridge, and the news fell like a bomb on the nation's conscience — not just regarding the issue of whether or not more lives were saved than extinguished by the bomb, but also concerning questions about how the world would be changed by the peaceful as well as the destructive atom.

The stigma of the atomic bomb was taken to heart by Oak Ridge's museum itself, established in 1949 as the Museum of Atomic Energy, but later renamed the American Museum of Science and Energy, to erase the word, "atomic."

"Aren't you ashamed you helped build a bomb that killed all those people?" a museum visitor asked Dorothy James, another one of Kiernan's subjects, who had been hired as a docent.

"The truth was, Dot did have conflicting feelings," Kiernan writes. "There was sadness at the loss of life, yes, but that wasn't the only thing she felt. They had all been so happy, so thrilled, when the war ended...Dot knew the woman wanted a simple answer, so she gave her one. 'Well,' she said, 'they killed my brother.'"

Moral ambiguity

In R.J. Cutler's documentary, "The World According to Dick Cheney," Cheney asserts that waterboarding is not torture and, at any rate, when faced between the choice between honor and duty, duty has to win.

War and politics are big reasons that decent people get involved in indecent causes. I'll leave out greed because few people would consider that motive morally ambiguous, except when it's pursued to assure the economic security of one's own group at the expense of another, in which case it's more like clan warfare.

Politics involves swaying opinions to gain support, and that brings us to a story related in this column on Oct. 10, 2011, about N.C. Gov. Charles Aycock.

Despite the fact that Aycock believed in Booker T. Washington's uplift movement — making African-Americans equals in society gradually through education — and despite the fact that he risked his governorship to uphold the "equal" part of "separate but equal" schools, Aycock had acted as the lead PR man in the Democrats' race-baiting campaigns at the end of the 19th century, with violent results.

The Democrats had lost the farmer vote block to Republicans, and let ends (their election) justify the means.

Aycock's devil's bargain has stained his reputation to the point where his name was recently taken off the state Democratic party's western fundraiser.

Likewise, it's fashionable in many circles to denounce anything associated with the Confederate flag, including the graves of Confederate soldiers who fought for reasons other than slavery — who fought, in fact, for homeland security, an issue corroborated by Northern exploitation and inflamed by slaveocrat propaganda.

Thus arises another cause of bad done by good people — self-righteousness. It's often deemed okay to hate people one has tagged as haters, without seeing the complexity or the humanity of the situation.

And that leads us to one of the most troubling and complex episodes in our region's history, the Shelton Laurel massacre. We're not talking about propaganda here, but about distortions of history to fit the world views of later generations.

Shelton Laurel horror

On Jan. 8, 1863, a group of Madison County mountain farmers ransacked Marshall for salt being withheld by the Confederate Army. A detachment of the 64th N.C. Infantry, headed, in lieu of Col. Lawrence Allen (on suspension for "crime and drunkenness") by Lt. Col. James Keith, rounded up 13 Shelton Laurel men and boys and, on Jan. 18, executed them without trial.

Keith, Phillip Paludan wrote in his book, "Victims," was a guerrilla fighter, and guerrillas, unlike regular troops, "attacked and fled, disguised themselves as civilians, shot noncombatants, (and) rampaged without orders from responsible superiors."

As Ron Rash, who wrote about the atrocity in his novel, "The World Made Straight," said, "I think the single most disturbing aspect of the Shelton Laurel massacre was the youngest victim was also the last one to die," and thus had to witness the murder of his kin.

The incident is used to support the notion that Madison County was Unionist. It was not. Yes, it voted against a convention to consider secession. That was on Feb. 28, 1861, before the firing on Fort Sumter and Lincoln's call for troops. After that, and for 17 months, not one Madison County resident is known to have enlisted in the Union Army.

Unionist feeling in Western North Carolina was aligned with strong feelings about the Revolutionary War, and the role that mountaineers had played in winning it. When President Theodore Roosevelt spoke in Asheville in 1902, he emphasized the Revolutionary War connection to help heal the sectional divide.

But during the Civil War, things were different. Through the course of it, Madison County enlistment in the Union Army did not top 5%. It is more accurate to describe resisters as disaffected Confederates.

Three of the executed Madison County men were 20-plus-year-olds who had deserted from the 64th N.C. regiment after having been drafted following the conscription law enacted by the Confederacy that year.

Two of the victims — Henry Wade Moore and William R. Shelton — according to "North Carolina Troops," had enlisted before their elders and were 17 and 16. In other words, they were volunteers who probably would have needed their parents' permission.

But wait, is that accurate?

Dan Slagle, a local expert on Shelton Laurel history, wrote the Citizen Times a week after the above column was published, adding invaluable information to my piece about the much-discussed Shelton Laurel Massacre in Madison County in 1863.

I had written that, as far as I could discover, there were no known Madison County enlistments in the Union Army until two years into the war. Slagle noted that "a short search through records of soldiers in the 1st TN Cavalry/4th TN Infantry" reveals that at least seven residents, whom he names, joined the Union Army in November of 1861.

For my statement, I drew upon the research of Terrell Garren, who had checked several Tennessee regiments, but not the 1st Cavalry/4th Infantry, for his book, "Mountain Myth." In his study, he allowed for about 200 omissions from his count, based on the huge number (2.3 million) of Union troops that would need to be examined.

Recently, Garren traveled to Nashville to look at more enlistments one by one. He found a total of 12 Madison County men in the 1st Cavalry/4th Infantry — the seven Slagle named plus Stephen Griffin, William Hall, Amos and Frances E. Hensley, and William Sinard.

These are the first 12 Western North Carolina men that Garren has found to have enlisted in the Union Army before 1863. That makes Madison County distinctive. Still, as far as total enlistments tell, the county was more than 90% Confederate; and about 97% early on.

Slagle cautions about my use of Phillip Paludan's book, "Victims," as a source, particularly in connection with the reasons for Col. Lawrence Allen's absence from command of his regiment (64th N.C.); and regarding the guerrilla tactics of acting commander, Lt. Col. James Keith.

Slagle is right again. Paludan's book, which John Inscoe (author of "The Heart of Confederate Appalachia") calls "excellent" and "the fullest account," is nevertheless controversial; and other accounts have emerged.

Paludan's attribution of Allen's absence from the Shelton Laurel action to suspension based on "crime and drunkenness" is a little bit of a leap, though documented by Gov. Zebulon Vance's letters and a contemporary Memphis newspaper account. Allen is owed a fuller look, if he were to be the main subject of a story.

Paludan called Keith a guerrilla fighter in an attempt to explain that his actions — executing 13 men and boys on suspicion without trial — violated orders and enraged Confederate leaders.

The massacre, Inscoe writes, represented "escalating tensions between lower-ranking troops and civilians, as guerrilla warfare blurred the lines between combatants and noncombatants."

The elusiveness of historical truth even pertains to the date of the massacre. Slagle stated that it happened on Jan. 19 rather than Jan. 18, 1863, as I had said. Most sources say "on or about January 18." I am researching the reasons why and the significance of the order of events.

In my article, I also wanted to highlight some larger truths. Even with the accounting of 12 Madison County men in the 1st/4th TN Union, the county registers more than 90% Confederate, putting notions of widespread Unionism in doubt.

Furthermore, Garren's and my investigation of the 13 Shelton Laurel victims revealed that two teens shot for being Unionist had volunteered in the Confederate Army, May 1862. Not only does this highlight the tragedy, it raises questions about generational divides within communities and maybe even families.

Garren's recent book, "Measured in Blood," took research into Civil War enlistments to a new level, examining every Henderson County soldier's record and following up with examination of census records and official war reports.

He also developed a system by which he could measure the nature of a soldier's involvement, distinguishing, for instance, between a "Confederate deserter, who goes over to the Union May 5, 1865," and "volunteers from the North who charged The Stone Wall at Fredricksburg."

Garren would like to see his research method picked up by others and applied to additional counties.

Rob Neufeld wrote the weekly "Visiting Our Past" column for the Citizen Times until his death in 2019. This column originally was published March 4, 2013, with an update from March 25, 2013.

This article originally appeared on Asheville Citizen Times: Visiting Our Past: Decent WNC people caught up in indecency