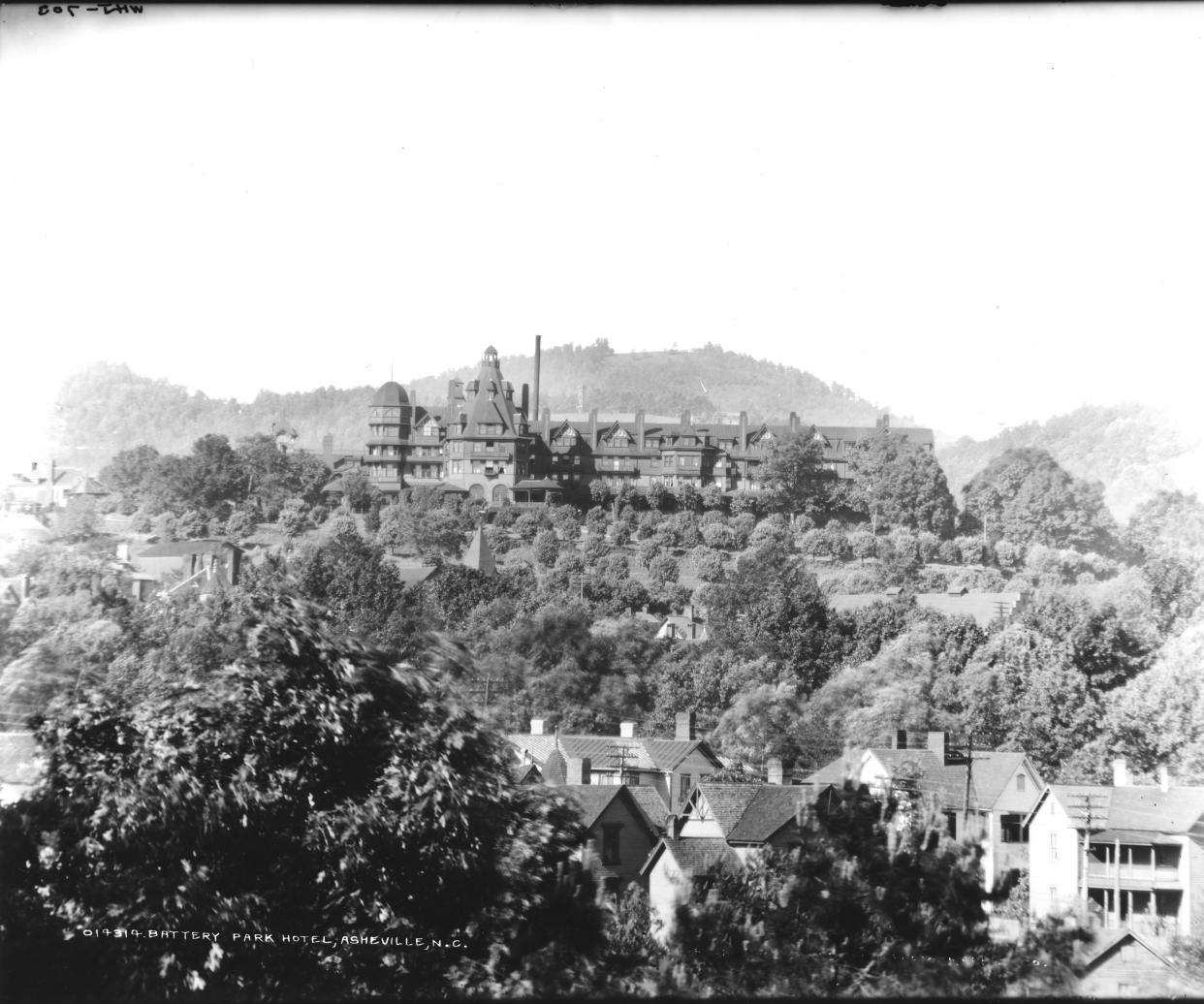

Visiting Our Past: A look at the 1st Battery Park Hotel

When Edwin Wiley Grove — self-made medicine magnate and visionary Asheville developer — bought the world-famous Battery Park Hotel from the Coxe family in 1921, he did not intend to tear it down. He meant to complement it with a new fireproof commercial hotel at the other end of the 10-acre hill on which the manorial, wooden structure stood.

In a letter to Tench C. Coxe dated July 25, 1922, Grove stated: "It is my idea to continue Battery Park Hotel as a strictly resort hotel keeping it open only for the winter and summer seasons, but to keep the new commercial hotel open throughout the year."

By December 1922, Grove had hired two local contractors — Julian A. Woodcock and Clyde S. Reed — to excavate the hill, which rose to 80 feet above Haywood Street at the north end.

The hill, formerly the site of a Civil War battery, contained no bedrock but instead exhibited a great deal of rounded creek stone and Indian arrow heads, signs that it once had been an island in an ancient waterway.

Excavation was soon followed by news of changed plans. The old Battery Park Hotel would not be saved. The new commercial hotel would go up on the hill's leveled site.

A fire in a watchman's shanty spread to the old hotel and sped its destruction.

Legendary hotel

The original, manorial Battery Park Hotel, built by Colonel Frank Coxe, opened July 12, 1886.

In its heyday, the establishment qualified as one of the world's social centers. In the late 1890s, newspapers reported, there developed a huge rush of passengers to Asheville and Hot Springs via the Southern Railway, the predecessor of which — the Western North Carolina Railroad — Coxe had helped finance.

As evidenced by the railway's slogan for the region — "The Land of the Sky" — scenery was the outdoor draw. The indoor one had to do with something that might be dubbed "The Brand of Whiskey."

"Dear Colonel Coxe," wrote E.P. McKissick, Battery Park's manager, on Feb. 12, 1897, "the status of the dispensary matter at present is that no bill has been introduced for Buncombe County so far but one will be introduced by a man named Chandler who is representative of this county."

The Florida crowd was beginning to turn toward Asheville. Dispensaries would regulate the sale of alcohol through county control and favor Battery Park.

"One unfortunate part of the fight against the bill," McKissick continued, "is that the bar-keepers in Asheville are divided, that is, the higher class of bar-keepers have been arrayed against by the lowest."

The people who stayed in the old Battery Park have contributed to its legend: George Vanderbilt, envisioning Biltmore Estate; Thomas Raoul, consulting with Coxe about building the Manor on Charlotte Street; members of the Southern Nation Park Association, foreseeing the Great Smokies National Park.

A Jan. 22, 1889, edition of the Asheville Citizen reported on the "multimillionaires" who were guests at the Battery Park Hotel that week. They included Mrs. Moses Taylor, wife of the retired president of City Bank, and notable mention in the 1904 publication, "The Ultra-fashionable Peerage of America"; and Mr. and Mrs. Hamilton Twombly, financial adviser to William Henry Vanderbilt and his wife, Florence Adele, Vanderbilt's daughter.

In with the new

The old hotel went the way of the Jazz Age. Upkeep was expensive; automobile tourists supplanted train travelers.

Steam shovels carted away Asheville's geographic prominence — directed by Grove, whose Grove Park Inn, built with Sunset Mountain stone, had opened July 12, 1913.

George Durner, son of Augustus John "Gus" Durner, superintendent of John M. Geary Co., general contractors for the new Battery Park Hotel, related boyhood memories of the project.

"When the Battery Park Hotel and the Grove Arcade were being built," Durner recalled, "you had a number of Black laborers that were digging ditches. They always would be singing a chant. If you were in my father's office with him on Haywood Street, you could hear this hum, and all of a sudden it would stop, and when it did, he would run like mad to the job because he knew there was ... an accident that had happened."

The workers also sang to their mules to keep them going without having to whip them. A song would be punctuated by "Gee" and "Haw" — go right and go left — as the mules dragged pans.

A water boy provided drinkable water, kept free of dust.

Skilled laborers built Grove's Battery Park Hotel with reinforced concrete, wooden studs and brick cladding. Dynamite was used to blast apart hills.

Durner reported that one blast, set off by an overlarge charge, caused a crack in the vestibule of the St. Lawrence Church. Another blast, reported in the Citizen on Feb. 13, 1923, killed Pomp Jenkins, a Back laborer buried alive when a charge was set off before he'd cleared away the area.

Grove had his plasterers memorialize his workers in sculptural reliefs above the ramps of the Grove Arcade across the street. You can see them today: medieval style icons representing an architect, a surveyor, a painter, a mason, a carpenter and a steam shovel operator.

Rob Neufeld wrote the weekly "Visiting Our Past" column for the Citizen Times until his death in 2019. This column originally published July 7, 2014.

This article originally appeared on Asheville Citizen Times: Visiting Our Past: A look at the 1st Battery Park Hotel