Visiting Our Past: Stargazing at our regional forerunners Guastavino, Blue Yodeler, Masa

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Every person is a legend, rightfully, to grandchildren and beneficiaries. So, too, is the loner, whose life symbolizes the human condition in the starkest way.

For instance, Wilma Dykeman began "The French Broad," her classic chronicle of our region, with the story of an anonymous man.

"The Negro camp was near those Flowery Flats," a former lumber camp paymaster informs Dykeman at Devil's Courthouse. The African-American workers had "died off so fast," he said; and "there was one I reckon I'll never forget. He was a giant of a man, dark as three o'clock ... (and) none of the rest of them knew him. Not even his name."

Dykeman's leadoff legend had died of a fever, "staring at the slab-sided wall for two days."

Rafael Guastavino

Despite the democratic attention we want and need to apply to every individual's time on earth, certain individuals participate in history in ways that make them favorite reference points in popular culture.

Some legends grow in stature after decades of recumbence. Many have seen their glory flourish in Western North Carolina.

A good example is Rafael Guastavino, Valencia-born architect of St. Lawrence Basilica who moved here in the mid-1890s for Biltmore Estate and died at his home in Black Mountain in 1908.

The Friends of the Guastavino Museum Project are active on the home site, located at Christmount Christian Assembly camp and conference center. Some Asheville community members hope to secure space for a small plaza across from the basilica, where the McKibbon Group has gotten the go-ahead to build a hotel.

Just within the last month and a half, the National Building Museum and National Public Radio have made Guastavino a national hot topic.

Blue Yodeler

So, what other area legends are seeing their stars brighten?

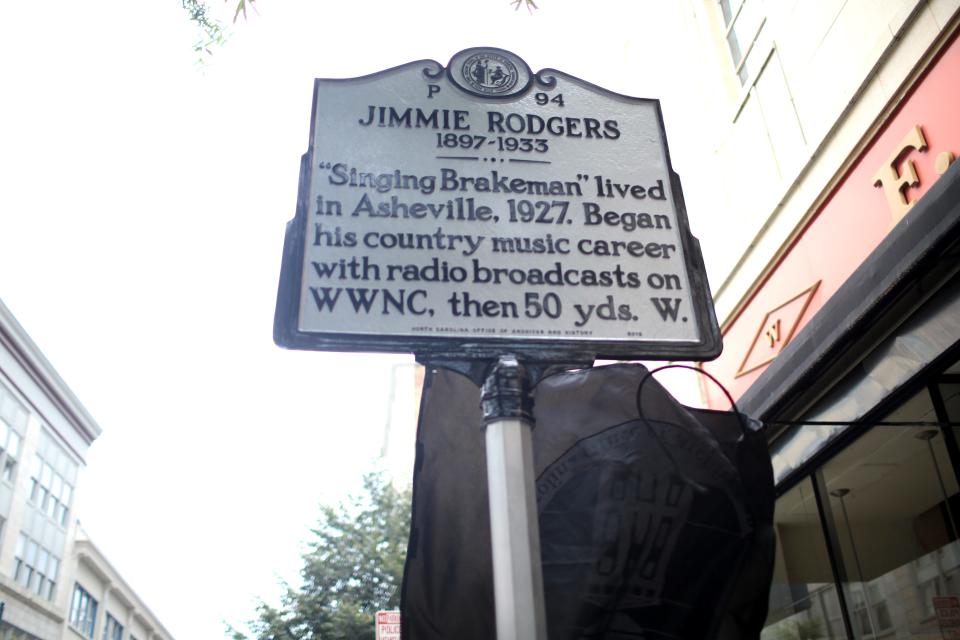

The historical spotlight is searching for more evidence of Jimmie Rodgers in Asheville.

Rodgers, the legendary country music singer, spent a significant period of his life in Asheville in the late 1920s. He may have composed his career-launching blue yodels here.

"In 1926, Rodgers and Carrie, his wife of six years, moved to Asheville, North Carolina, and organized the Jimmie Rodgers' Entertainers, a hillbilly band comprising Jack Pierce (guitar), Jack Grant (mandolin/banjo), Claude Grant (banjo), and Rodgers himself (banjo)," Nolan Porterfield wrote in "Jimmie Rodgers: The Life and Times of America's Blue Yodeler."

Rodgers was a railroad worker, like his father, but after contracting tuberculosis, he left that job and gained the opportunity to pursue his childhood passion, music.

There's evidence that Rodgers worked as a police detective, cab driver and janitor in Asheville. On April 18, 1927, he performed a show on the newly established radio station, WWNC.

The station was started Feb. 21, 1927, by the Asheville Chamber of Commerce for reports on weather and road conditions and for music at night.

WWNC was a pioneering country music station, placing its broadcast tower in the Flatiron Building in Asheville and stringing a wire over to the county courthouse for increased range.

It was in Asheville that Rodgers read an ad placed in a Bristol, Tenn., newspaper by Ralph Peer, recruiter of so-called "hillbilly" music for Victor Records.

Rodgers had been playing mostly New York songs for his audiences, but Peer wanted some country stuff, and Rodgers composed Blue Yodels numbers 1, 2 and 3 to fill the demand.

Jimmie Rodgers' records became top-sellers, and he toured the country. He completed his final recording session in New York in May 1933 and soon after died of tuberculosis.

Again, from Porterfield, we learn that Rodgers' uncle, John Fullam, a railroad conductor in Asheville, helped the Rodgerses make the transition here; and John's son, Jack, a fireman, secured him temporary bedding at Engine Co. No. 2.

The Fullams' friend, J.D. Bridgers, gave Jimmie a job as a janitor in his apartment building and lodging in a cottage behind it. In the meantime, Rodgers and his band performed at area hotels and resorts.

What looked like itinerant non-history in 1927 turned out to be epochal; and the effort is afoot to fill out the picture.

George Masa

The George Masa legacy has grown from photos published in 1920s and '30s regional travel promotions to reverence of him as the archetypal disciple of Great Smoky Mountains spirituality, the iconic photographer and the most reliable cartographer.

His story — including his remarkable and, in some ways, sad life (he died of tuberculosis in 1933) — keeps growing, as new documents emerge.

Born Masahara Izuka in Japan in 1881, according to his gravestone in Riverside Cemetery (the date and spelling vary in other sources), Masa came to the U.S. between 1906 and 1914, presumably to continue civil engineering studies.

He'd already converted to Christianity under the influence of a Methodist minister in Japan, as revealed in a friend's testimony in Masa's obituary.

Izuka changed his name to George Masa in the States and, after his father died in 1913, followed his artistic dreams. He arrived in Asheville in 1915, got a job as a valet with Fred Seely at Grove Park Inn and as a woodworker in Biltmore Industries.

He practiced photography, further pleasing Seely and his patrons, and opened his first photo studio with H.W. Pelton.

In 1995, Bill Hart, writing an article on Masa for Robert Brunk's "May We All Remember Well," worked with Pack Memorial Library librarians to discover Masa materials among the Horace Kephart archives there. The attention led to the recognition of Masa photos in the Ruth E.K. and Bess J. McDowell scrapbooks.

In 2002, Howard McDonald's donation of materials to the Carolina Mountain Club Archive in UNC Asheville's Special Collections added new Masa materials.

A year later, Paul Bonesteel Films produced the acclaimed documentary, "The Mystery of George Masa," and in 2009, Ken Burns' "The National Park: America's Best Idea" series showcased Masa in a major segment.

Recently, Bonesteel received and translated letters Masa had written to Japanese friends in the U.S. They had been in the possession of the family of Dr. Henry P. May, an Asheville dentist with whom Masa boarded in the early 1930s.

Debt that Masa was paying off while struggling to make a living as a photographer in Asheville had been incurred, it came to light, through an honorable act.

Masa's close friend, Shoji Endo, called Yama, had spent a good portion of a common fund used by Masa's group of traveling Japanese workers and then committed suicide. Masa took on Yama's financial burden.

"Yama's whole life was a drama, a tragedy," Masa wrote an administrator of the fund. "I am doing this for the sake of fulfilling Yama's will."

He also noted, "When the right time comes, the cherry blossoms deep in the mountains will show their color on their own accord. I am a sculptor and photographer. I am also taking correspondence courses in mining engineering."

Rob Neufeld wrote the weekly "Visiting Our Past" column for the Citizen Times until his death in 2019. This column originally was published May 6, 2013.

This article originally appeared on Asheville Citizen Times: Visiting Our Past: Stargazing at forerunners Guastavino, Rodgers, Masa