Visiting Our Past: Wolfe's ancestry crossed at Gettysburg

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

On June 30, 1863, 13-year-old Oliver Gant watched Confederate troops march past his home in Pennsylvania.

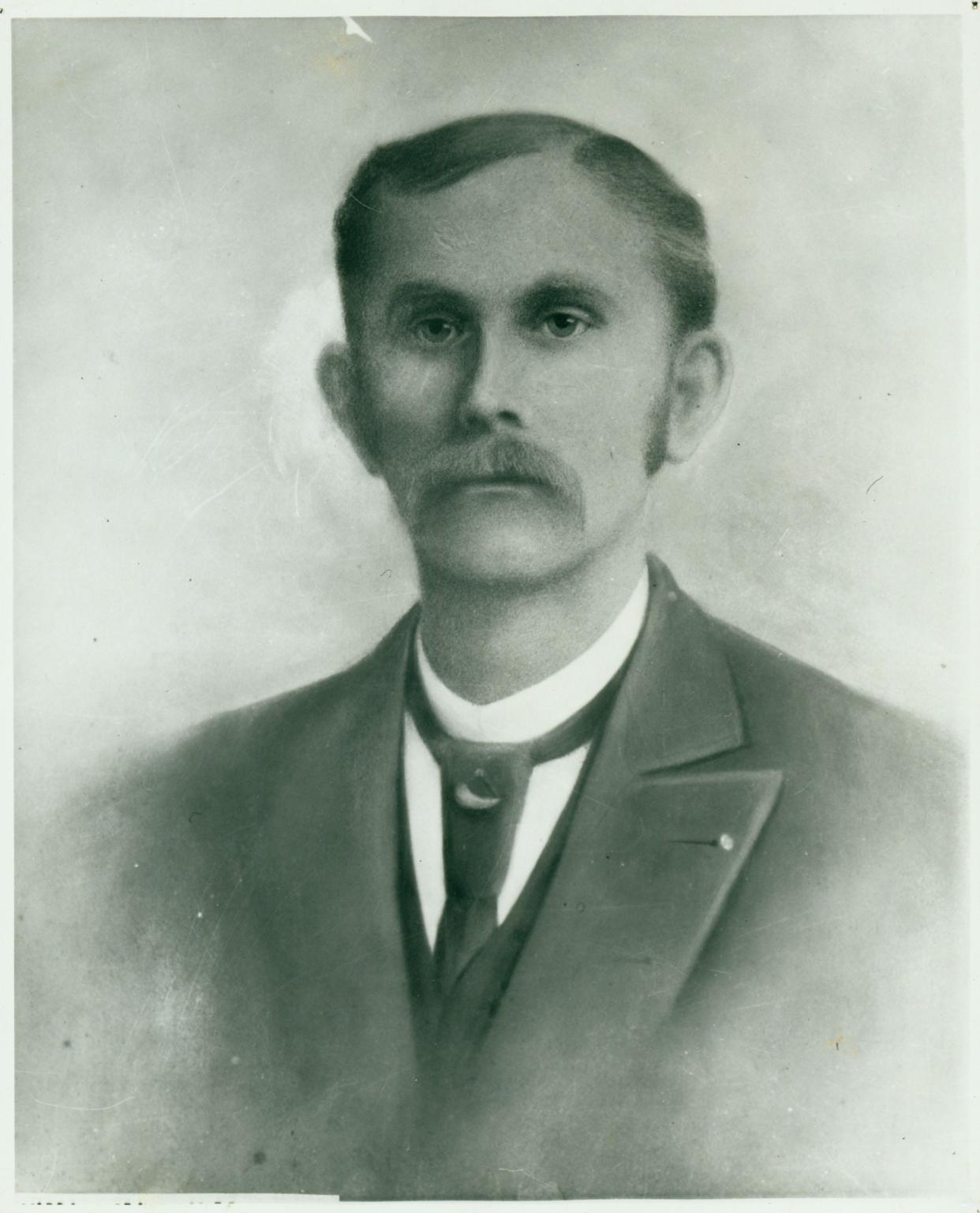

Gant is Thomas Wolfe's fictional representation of his father, William Oliver Wolfe, whose experience of the Civil War he re-created in the cut-out portions of "Look Homeward, Angel" later restored in "O Lost!"

After Chancellorsville, General Lee had decided to invade the North and use northerners' distaste for war to advantage.

When, in June, the Federal Army of the Potomac changed generals — Meade coming in for Hooker — Lee crossed the Blue Ridge and headed toward Harrisburg. Then he heard that Meade's troops were in Gettysburg, and he moved divisions South to engage them.

The soldiers on that trek are who Oliver sees. His older brother, Gilbert, beside him, "stood planted on spread legs, paying the enemy back stare for stare with hard unafraid defiance," Wolfe writes.

But, Wolfe continues, that "scarecrow army was in a cheerful humor. It was going to fight; it was going to fight barefooted." Part of General Henry Heth's brigade, these men had "come in from Lee's base in Cashtown to look for shoes." News was, there was a cache in Gettysburg.

Some of the soldiers were from Western North Carolina.

Brig. Gen. James Johnson Pettigrew's brigade of Heth's division included the 26th N.C. Infantry Regiment, which Zebulon Vance had started in Asheville in 1861 as the Rough and Readies; and which suffered, July 1, the highest casualty rate of any regiment, North or South, in a single day.

The deadliest day in WNC history happened 500 miles away. The father of the region's greatest writer had witnessed the harbinger.

In the fiction, the author's father meets the man whom he'd get to know 20 years later as his wife's uncle. Bacchus Pentland — in real life, Bacchus Westall — was preaching all the way to Gettysburg.

"There was one," Wolfe writes, named Bacchus Pentland, "who sang hymns while he marched, and preached while he waited." "He was dressed in shapeless rags; his large odorous feet were bandaged with wound sacking; he gave off from his thick hairy body a powerful decayed stench. In moments of piety, his comrades called him Stinking Jesus."

Bacchus let his fellows taunt him, as they all stood in line for cups of water from the Gant well. He drew a roll of paper from his shirt and opened it to decipher that Christ will "be here a-judgin' an' dividin' by eight o'clock to-morrow morning," according to Ezekiel.

"Hit's a-comin!" Bacchus prophesized. He'd also prophesized the end at Manassas, Fredericksburg, and the Wilderness. He was kind and simple, and the soldiers loved him. He could shoot "the fingers off a Yankee hand at ninety yards" and send his enemies into eternity with the promise of Heaven.

After the battle, Oliver looked for Bacchus' body, and did not find it.

Bacchus made it back home, as did the surviving original Rough and Readies. Second Lieutenant William M. Gudger and six of his men — John H. Walker, James T. Bird, Columbus Cooper, Ezekiel Campbell, Lemuel Jones and John R. Patillo — were released at Appomattox to walk 300 miles home in April 1865. One of the men was wounded, and Gudger was given a horse to carry him.

Rob Neufeld wrote the weekly "Visiting Our Past" column for the Citizen Times until his death in 2019. This column originally was published Dec. 26, 2011.

This article originally appeared on Asheville Citizen Times: Visiting Our Past: Wolfe's ancestry crossed at Gettysburg