Vitamin B12: a 92-year-old’s 'reason for being'

Editor's Note: The following is part of a class project originally initiated in the classroom of Ball State University professor Adam Kuban in fall 2021. Kuban continued the project this spring semester, challenging his students to find sustainability efforts in the Muncie area and pitch their ideas to Deanna Watson, editor of The Star Press, Journal & Courier and Pal-Item. This spring and summer, stories related to health care have been featured.

MUNCIE, Ind. – At 12 years old, Micki Wise got her first gray hair.

Five years later, she accompanied her mother to an appointment with their family doctor. When he entered the room, the doctor immediately noticed Wise’s pale complexion and asked her if she felt OK.

“Oh, I’m just tired,” Wise replied.

But the doctor suspected more: “I don’t like the way you look. I want you to come back to the office.”

Wise said she remembers being tired, pale and prematurely graying in her pre-teen years, but every one of her many blood tests came back normal. This time, her doctor tested her specifically for “an old person’s disease,” as Wise recalls.

“Because of the gray hair—I think that’s why he tested me for pernicious anemia,” Wise said. “But doctors weren’t testing for that back then.”

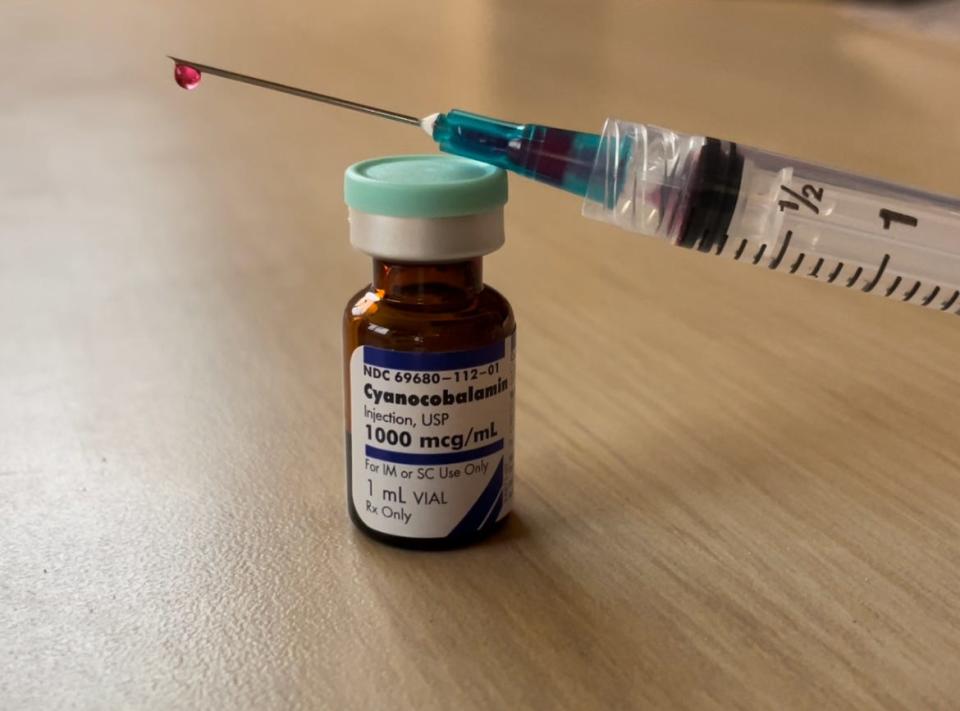

She was admitted to the hospital in 1948 when her blood test confirmed pernicious anemia, a condition that results from the intestine’s inability to absorb vitamin B12, therefore, decreasing the body’s red blood cells, according to Penn Medicine.

Meat-eaters rejoice

B12 deficiency doesn’t just affect those with pernicious anemia, though. According tothe National Blood, Heart and Lung Institute, vitamin B12 is required for the human body to make healthy red blood cells, white blood cells and platelets. But we don’t create B12 naturally, so we have to eat food that contains it—lean red meat, chicken, fish, animal byproducts, etc.—or take supplements to balance blood levels.

People like Wise have a harder time absorbing B12 from food because their stomachs lack a protein called intrinsic factor. However, other variables contribute to the common nature of B12 deficiency in people all over the world.

Vegans and vegetarians often develop a deficiency in B12 due to their diet’s lack of animal products but autoimmune diseases, high alcohol consumption and some medications — among other things — can have the same effect, according to The National Blood, Heart and Lung Institute. Without the proper treatment, vitamin B12 deficiency can cause serious complications such as bleeding, infections, and permanent nerve or brain damage.

The treatment plan for Wise’s condition started with cobalamin (B12) pills, but her levels remained low. When they tried shots of cobalamin, her levels steadily rose. She said she’s taken B12 shots every month for 74 years.

But like all drugs, overconsumption of vitamin B12 is not advised. According to a 2020 case study published in “Clinical Toxicology,” excess vitamin B12 can cause adverse reactions such as acne, nausea and increased blood pressure. While the case study concluded the subjects’ reaction to cobalamin was “unusual and unexpected… it reminds us that the administration of any drug is not entirely safe,” even ones that are considered safe like cobalamin.

What is your reason for being?

Two years ago, Wise read the book, “Could it Be B12?” by Sally M Pacholok, R.N.., B.S.N. and Jeffrey J. Stuart, D.O. She originally thought her symptoms were unique to her condition, but she learned that low B12 levels can contribute to all types of illnesses and problems from Alzheimer’s to colon and stomach cancer and even the inability to conceive, according to the book.

Now, at 92 years old, Wise’s mind is still sharp; she recently renewed her driver’s license, and she takes every opportunity to advocate for vitamin B12.

“My father died of stomach cancer six days after his 42nd birthday; my mom died at 57,” Wise said. “I would have never made it to 92 without B12 — I would have been dead.”

Since reading “Could it Be B12?” Wise takes handouts that detail the dangers of B12 deficiency in her purse wherever she goes. Anyone lucky enough to engage in a conversation with Wise will likely be asked, “What are your levels?”

“My reason for being is to pass those [papers] out to everybody — people I don’t know, strangers — if they have a minute and talk to me, I tell them my story,” Wise said. “That’s why I’m still here.”

This article originally appeared on Muncie Star Press: Vitamin B12: a 92-year-old’s 'reason for being'