Voices: Are the economic sanctions on Russia yielding desirable results?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

By now, Russia should be in economic ruin. So much so that public pressure would have demanded a negotiated settlement with Ukraine.

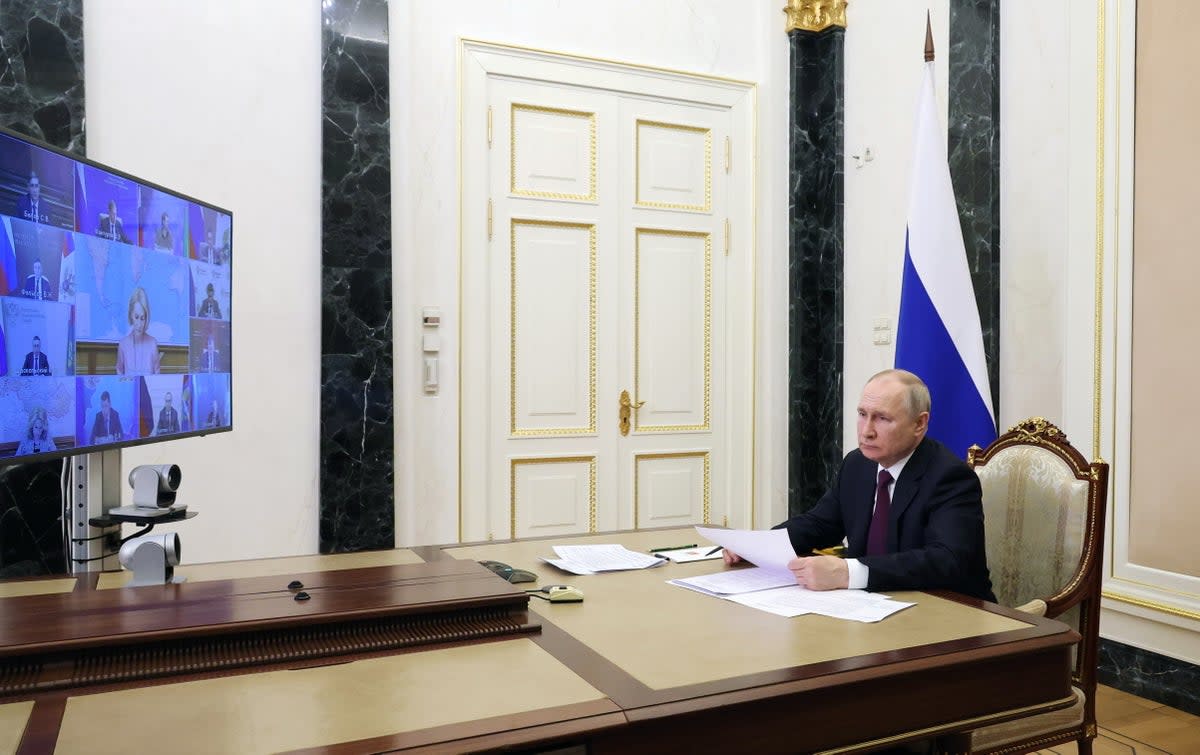

It simply hasn’t happened. Instead, the country’s economy is ticking along, and has done so pretty much ever since Vladimir Putin gave the order to invade Ukraine. The rouble fell at first, then soon bounced back. Russia has been able to take advantage of higher oil and gas prices, caused by its own aggression. Imports dipped for a while, but now they’ve returned to their pre-war levels.

Russia has suffered military setbacks and lost substantial numbers of troops, but unless they’re directly affected, for most Russians life is pretty much the same as before. Thanks to this, and Putin’s repression of internal dissent, there is no groundswell calling for withdrawal. Provided it can continue to access military supplies, Russia can carry on pursuing the conflict.

Yet, the US government in March 2022 was predicting the economy would soon “contract as much as 15 per cent”, and that the raised living standards enjoyed by Russians over the past two decades would be wiped out. The exodus of more than 400 multinationals, many of them in consumer goods and hospitality, would deny Russians the items and luxuries they’d come to take for granted.

The application of sanctions was meant to bring Russia to its knees. It’s a policy that has not worked – at least not to the degree that was intended. Since 2014. when Russia attacked Crimea, there have been 10 rounds of punitive measures. This weekend’s G7 Summit sees number 11.

Castellum.AI, which monitors embargoes against Russia, says that prior to the G7 meeting in Japan, 12,616 sanctions were issued post the invasion, on top of the 2,695 imposed from 2014. Nearly 10,000 are against individuals. Russian gas, coal and oil exports are restricted, along with travel, the sale of luxury goods, professional services, access to International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank funds, sovereign debts, and Russian banks’ use of the international payments system, Swift. Some $300bn of Russian assets have been frozen.

At the G7, UK prime minister Rishi Sunak persisted with the tough rhetoric, saying he wished to ensure Russia “pays a price” for the war in Ukraine. Russian diamonds, copper, aluminum and nickel imports would be added to the barred list. In all a further 300 Russian entities, including individuals, ships and aircraft, will now be blacklisted.

The G7 leaders said: “We are imposing further sanctions and measures to increase the costs to Russia and those who are supporting its war effort.”

Sanctions have long been the weapon of choice of political leaders wishing to curb a rogue country’s behaviour. It is much more preferable to the sight of troops returning home in body bags.

The problem is, they rarely work. One example often cited is the banning by the United Nations of South African trade during apartheid. In reality, it was not the economic isolation, which was endured for years, that made a difference, but internal demands for the suffering and bloodshed to cease.

In that case, the ban was applied by the UN. With regard to Russia, bans have been implemented by the US, EU, UK, Switzerland, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and Japan, but not by the UN, and not by the rest of the world; the “Global South”, which comprises South America, Africa, Middle East, India and Pakistan, China and the rest of Asia.

The result is that half the world is still open to trade with Russia. Putin has been able to sell oil and gas to China and India. Members of his close circle, the oligarchs, hit by individual measures, have relocated from London, New York and Paris to the likes of Dubai and carry on enjoying their super-rich lifestyles. Probably, too, the influence of the oligarchs on Putin has been exaggerated – if they have complained, their moans have fallen on deaf ears.

Local entrepreneurs, many of them former staff, have taken over the businesses in Russia of the departed foreign firms. Countries that aren’t bringing sanctions have nipped in with their own products, replacing those now barred.

At the same time, “parallel” imports – illicit sales to Russia from the West via a third country – have exploded. Armenia is one such hub, Kazakhstan and Serbia are others. In 2021, Kazakhstan exported no washing machines to Russia; this year it will send 100,000. Serbia used to export less than $10,000 worth of mobile phones to Russia; now its shipments are totaling tens of millions of dollars.

While sanctions are not achieving the desired result, they are having some impact. They’re certainly an inconvenience, and over time the Western companies will be missed. Likewise, the oligarchs do not have the total freedom they once did.

They might not be the magic cure, but it is possible that sanctions are preventing Putin from expanding his military push. He’s left locked in a stalemate and, so the thinking goes, will eventually call a halt. There’s some distance, and doubtless still more sanctions to be applied, before that point is reached.

Chris Blackhurst is an award-winning writer and commentator, and a former editor of The Independent. He is the author of The World's Biggest Cash Machine, due to release later this year