Voices: The escape of terror suspect Daniel Khalife exposes a prison system in crisis

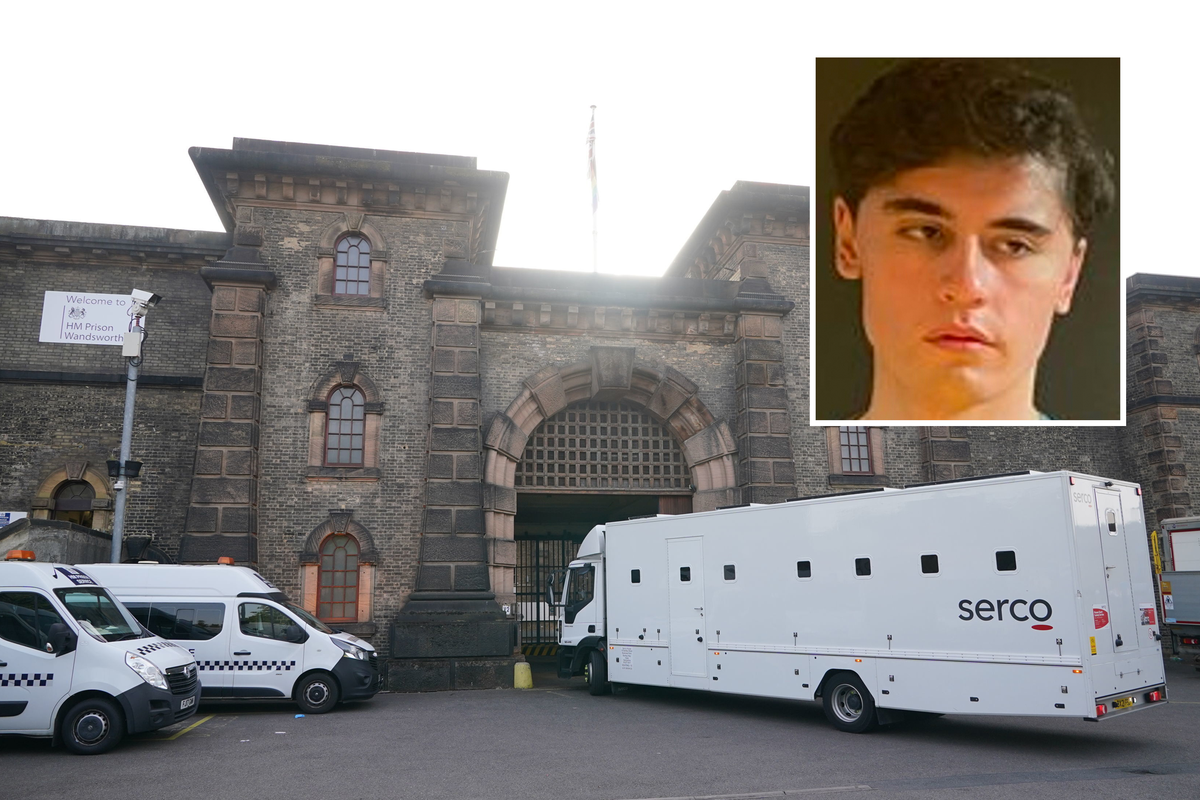

The escape by Daniel Khalife from Wandsworth Prison on Wednesday while on remand awaiting trial for terrorist offences is one of the most serious incidents in the prison system in recent years.

Escapes from prison are rare events – at most one or two a year over the last decade – but the seriousness of Khalife’s alleged offences makes this exceptional. But it is not a surprise. There has been warning after warning about the dangerous state of our prisons and Wandsworth has been known to be one of the most troubled.

There is much we don’t know at present about the immediate circumstances of the escape. Was it spontaneous or long planned? Did he have assistance inside or outside the prison? What checks were done on the vehicle it is reported he hid on to escape? Perhaps most importantly, we don’t know the justification for allocating him to a local prison like Wandsworth rather than a high security prison like HMP Belmarsh or for letting him work in a trusted kitchen job.

Wandsworth’s role is to hold most of London’s remand prisoners, but those accused of terrorist offences are usually sent to Belmarsh in recognition that even in the best of times, prisons like Wandsworth do not offer the right level of security. Prison kitchen jobs have to be allocated very carefully – not just because of the obvious availability of knives, but because those prisoners have access to both external suppliers and all parts of the prison to deliver food, making it ideal for obtaining and distributing drugs and other contraband.

But when the system is chronically overcrowded, prisoners will be sent to where there is space rather than where they would best fit. And prisoners need to be fed – so when a prison is short staffed, a prisoner who appears competent and trustworthy may end up in the kitchens because they can get an essential job done. A question will be whether the operational requirements of the system as a whole and the prison took precedence over a proper risk assessment.

We don’t know about the immediate circumstances of the escape – but we do know the systemic issues that lay behind it. Only last month, Charlie Taylor, my successor as chief inspector of prisons, warned of an “overcrowding crisis” in our prisons. In February this year Dominic Raab, then the minister responsible for prisons, had to write to the lord chief justice to warn him about the problems prisons were facing and their inability to carry out some basic functions.

Overcrowding is not simply a matter of the physical space available but also whether there are sufficient staff to keep prisoners safe, secure and purposefully occupied. And this is not just a matter of treating prisoners themselves humanely – but as the Khalife case shows, it is about keeping the public safe from prisoners who need to be locked up, and being able to do the work that makes it less likely that prisoners will reoffend and create more victims when they are released.

Wandsworth exemplified these problems. After a previous escape in 2019, the prison inspectorate warned in 2022 that physical security was weak and, in a follow up inspection later that year, they reported the prison remained very overcrowded with escalating levels of violence. In July the official statistics show the prison was holding 1,623 men against official capacity of 950.

The prison is chronically understaffed and many of those it does employ are not able to undertake normal operational duties. The local MP has reported that on one day in December 2022, a third of shifts were left uncovered. And of those who are at work, previous cutbacks caused the disproportionate loss of experienced staff so that many of those who remain, however willing, are young and inexperienced.

Prison security is more than a matter of locks and bars. Prisons run on dynamic security in which prison officers have the time to get to know prisoners and observe them – so they can tell if someone or something is a bit different today or a bit tense – and have sufficient relationships with prisoners, most of whom want a quiet life, to be tipped off if someone is going to do something that disrupts the prison. It appears that in Wandsworth too many staff did not have the experience, time and relationships to pick up the signals that something was not right.

There are already reports that “sources” are briefing that the governor and officials “have questions to answer”. I am sure they do. Katie Price, the governor of Wandsworth, is one of the best and most highly regarded governors in the country and what she has to say will be important.

But there are serious questions for the ministers and senior officials too. It would be outrageously unfair if they are able to push the blame onto those who were trying to manage the system while avoiding responsibility for the policy and resourcing decisions they made and that made the system almost unmanageable. As well as unfair, it would avoid learning the bigger lessons that need to be learnt. They have certainly been warned about the crisis in the system as a whole, but what warnings did they have about the state of Wandsworth prison, and what did they do in response?

When the spy George Blake escaped from Wormwood Scrubs in the 1960s, Lord Mountbatten’s independent inquiry led to wholesale changes. Ministers have now announced they will be an independent inquiry into Khalife’s escape. That enquiry must not stop at the prison gate, but must be able to examine the responsibility of successive ministers and senior officials, and address the wider systemic issues that underpinned this specific incident.

Professor Nick Hardwick was Her Majesty’s chief inspector of prisons between 2010 and 2016