‘Their voices made me cry.’ How two Black singers are breaking barriers at Miami opera

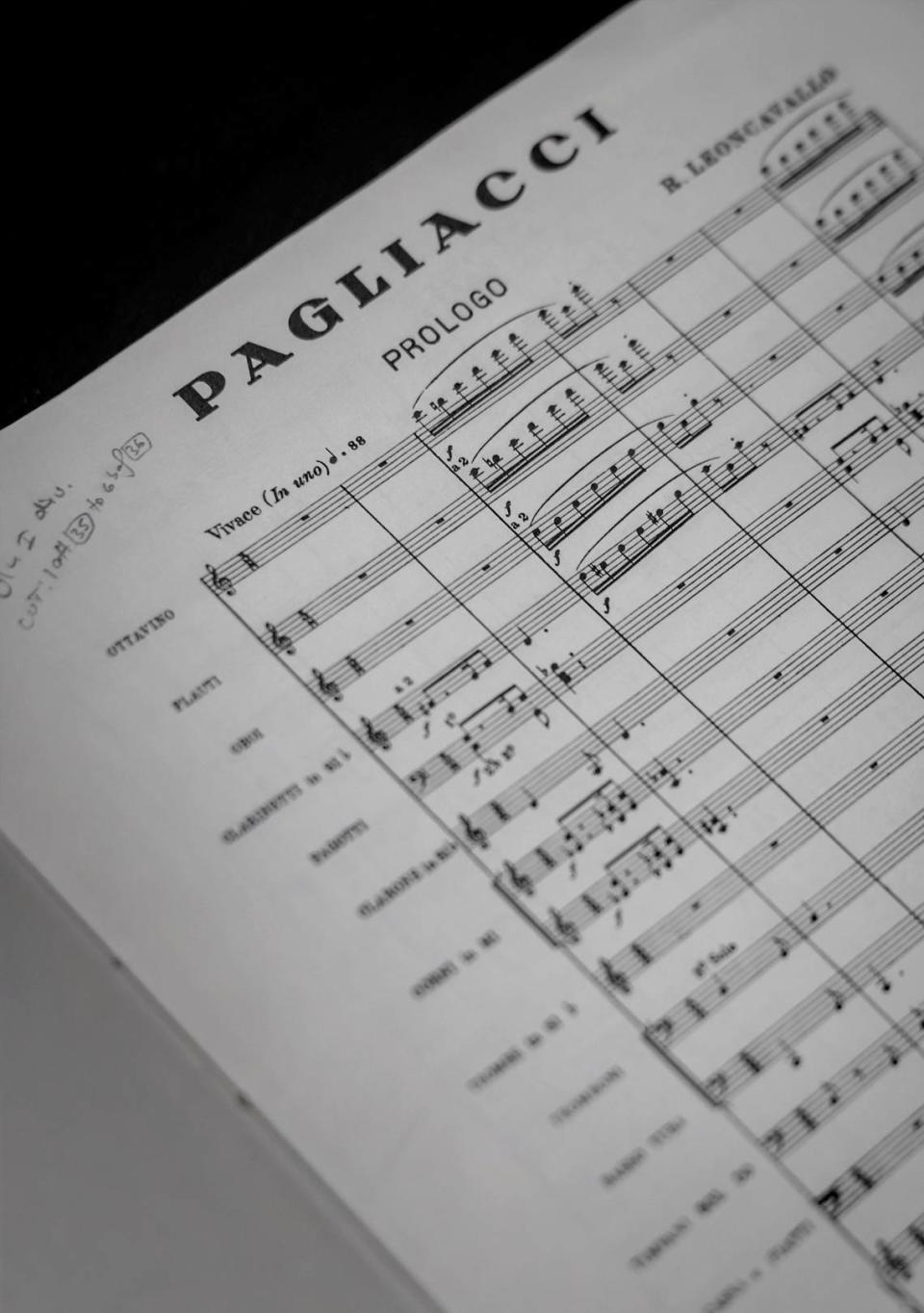

Audiences enraptured by the Florida Grand Opera’s production of “I pagliacci” and lead singers Limmie Pulliam and Kearstin Piper Brown gave standing ovations to the classic play within a play. But they may as well have been shouting “Bravo!” to the play within a play within another play portraying real life, the story of a struggling South Florida company that first staged “Clowns” in segregated 1942 Miami now daring to reinvent itself by spotlighting two Black singers smashing stereotypes in a traditionally white, wealthy art form waning in popularity.

“As a Black opera singer I know people are going to see me before they hear me. They’re going to see my skin before they hear my voice,” said Piper Brown, a soprano cast in the role of Nedda. “I long to be heard before I’m seen. I long to change minds and help everyone understand that when people of color thrive, we all thrive.”

She is making her debut as Nedda for the Florida Grand Opera, which will stage its final two performances of “I pagliacci” Feb. 8 and 10 at the Broward Center for the Performing Arts after earning rave reviews for three shows last week at the Adrienne Arsht Center in Miami.

“This production with Kearstin means a lot to us,” said Pulliam, a tenor who plays Canio, the star actor in a traveling troupe who is betrayed by his wife. Stabbed by the heartbroken Canio, Nedda and her lover Silvio die, as the on-stage audience in a small Italian town reacts with confusion and horror. Is it real or part of the show? He declares “This comedy is over,” and the curtain falls.

“Early in my career it was not unusual for me to be the only Black face in the entire theater,” Pulliam said. “Today, South Florida gets to see two African-American singers at the height of our vocal abilities when typically the only time you see more than one African-American on an opera stage is in ‘Porgy and Bess.’”

Opening minds through opera

FGO’s production is a milestone. The oldest theater arts organization in the state opened with an all-white cast premiere of “I pagliacci.” Eighty-two years later, new general director Maria Todaro and new president Tina Vidal-Duart share a vision for a renaissance of FGO, which was financially decimated by COVID. They want the opera and its fans to reflect the diversity of South Florida. Pulliam and Piper Brown personify that goal.

“We’ve got to provide more opportunities for Black and brown singers,” Pulliam said. “That’s the only way to grow our audience and our industry. It is frustrating that in 2024 we’re still calling a production such as this one ‘groundbreaking.’

“I’ve been told audiences would not be comfortable seeing an African-American male in a romantic role with a white female. To think an opera singer cannot be believable because he or she is Black shows you how far we have to go.”

Todaro recalls how her father, Italian opera singer Jose Todaro, used to play the role of Othello in black makeup.

“Opera has a reputation of being written by white people for white people,” she said. “But opera has made a lot of progress in a short time. Limmie and Kearstin are exquisite singers. Their skin color did not sell me. What sold me, what moved me was when they opened their mouths. Their voices made me cry.”

Todaro grew up in the opera world. Her mother is Brazilian mezzo-soprano Maria-Helena de Oliveira. Todaro sang as a mezzo-soprano herself. She is married to baritone Louis Otey. She has directed more than two dozen productions and co-founded the Hudson Valley International Festival of the Voice.

Todaro set the Festival’s 2019 production of Donizetti’s “L’elisir d’amore” in Ghana.

“My entire cast was African-American,” she said. “We incorporated African drumming into the orchestration and African choreography into the wedding scene.

“We know opera can open minds. We know telling stories through song has an ancient, transformative power to unite and elevate communities. I came here because there was a crisis and because Miami offers an opportunity for opera activists to modernize our art form and use it as a tool to heal injustice and division.”

Changes since George Floyd’s death

“The opera industry is in a much better place in the last several years since George Floyd was killed because of the Black Lives Matter movement,” said Piper Brown, 45. “The people who do the hiring did not trust Black performers in the past. But it feels like I’m being entrusted now. That comes with a lot of pressure. You’re representing an entire population and the next generation. You can’t just be good, you have to be better or your race can become a reason you and others like you won’t get jobs. We also worry that the Black Lives Matter influence will wear off and people will say, ‘OK, we did our part for diversity and that’s enough.’

“While I am proud to be a Black opera singer, it’s frustrating that such an imaginative industry still has some of the most close-minded people making decisions. It’s their fear of losing a grip on power, power that was made possible by institutionalized racism. We have to reject that fear.”

Piper Brown felt a keen sense of change when she visited the Historic Hampton House Hotel in Miami’s Brownsville neighborhood. The hotel, now a museum, was a mecca for Black performers and tourists when Miami was a segregated city and Miami Beach was a “sundown town” — where Black people were banned at night unless they had special permission. The great Black artists of the era performed in Miami Beach hotels but could not stay in them.

The Hampton House has preserved the favorite rooms of Martin Luther King Jr. and Muhammad Ali and displays photos of its famous guests, such as Louis Armstrong, Nina Simone, Ella Fitzgerald, James Brown, Aretha Franklin, Harry Belafonte, Diana Ross, Stevie Wonder, Marvin Gaye. And Frank Sinatra. The Rat Pack stayed at Hampton House in solidarity with Sammy Davis Jr.

“People always felt the shows performed here or in Overtown were better than the ones in Miami Beach,” said executive director Jacqui Collyer. Her mother, who is 92, still has the ID card she was required to carry when she worked in Miami Beach.

Piper Brown, who grew up listening to her mother’s Johnny Mathis records, said she could hear strains of jazz, soul and R&B sung by legends as she walked around the hotel.

“What a gem,” Piper Brown said as she stood by the pool. “I feel like I’ve been let into a secret Miami and experienced a rite of passage.”

Childhoods filled with music

Like Pulliam, who is from Kennett, Missouri, Piper Brown grew up in a household filled with music and was steered toward singing by her high school music teacher. As a child in Alexandria, Virginia, she played violin and flute, listened to gospel music with her grandparents and once a year was treated to a show at the Kennedy Center (and a new dress) by her parents.

She did not hear her first opera until she was a sociology and music major at Spelman College in Atlanta. Her ethnomusicology thesis was on the influence of African music on Cuban music.

She never thought about becoming an opera singer until she worked as a producer on a classical music show at an National Public Radio station. She booked and interviewed classical artists, and, “I got jealous.”

She was accepted into Northwestern’s graduate music school “but felt like a fish out of water with all these conservatory students,” she said. “After graduating, I wasn’t sure. Opera singers are weird.”

But, inspired by the success of Leontyne Price, Jessye Norman and Roberta Alexander, Piper Brown auditioned and pursued roles. An overseas tour in “Porgy and Bess” exposed her to agents. A 2005 performance in Italy opened eyes. Kathleen Battle got her a job. Then in 2009 she placed third in the Monserrat Caballe voice competition in Spain. The winner and runner-up were also Black singers.

Piper Brown said her breakout lead role was Esther the seamstress in a 2022 operatic adaptation of Lynn Nottage’s play “Intimate Apparel” at New York’s Lincoln Center, part of the PBS Great Performances series.

Her two sons, 10 and 12, traveled with her when they were toddlers. Her husband, a urologist, holds down the household in Rochester, New York, while she’s on the road to New Orleans, San Francisco, Moscow, Vienna, Amsterdam. She’s appearing in Terence Blanchard’s “Fire Shut Up In My Bones” at the Metropolitan Opera in New York in April.

“It’s a hard job but I’ve always been drawn to hard things,” she said. “Challenges energize me.”

Pulliam, 43, is performing the role of Canio and one of the most memorable arias in opera for the second time in his career.

The youngest of 10, he grew up singing in his pastor father’s church. His father played guitar, and a cousin was a gospel singer who recorded with Stax Records in Memphis.

“I joined my middle school choir and hid in the bass section,” Pulliam said. “In high school, my music teacher Viretta Sexton discovered I had extensive range. I was impersonating Stevie Wonder and she said, ‘This kid has a voice.’

“One day she asked me to stay after school and I figured I was in trouble for making people laugh. But she asked me if I’d ever heard of opera. No, ma’am. She handed me a piece of sheet music and a cassette tape. It was Luciano Pavarotti singing ‘Una fortima lagrima.’ I imitated him, mimicked the words. I got hooked on that sound, how opera singers could project their voices without a microphone over a full orchestra. I was blessed to have her work with me and put me on a path that’s opened the entire world to me.”

Pulliam’s piano teacher in Kennett — a small town that has produced a number of singers and songwriters — was Sheryl Crow’s mother, “a beautiful soprano who practiced opera duets with me.”

Pulliam stopped playing football, basketball, baseball and track to concentrate on singing. He enrolled at the Oberlin Conservatory of Music where he studied under Richard Miller, “who was brutally honest with me and said as a Black singer I would never have the privilege of being mediocre. I would always have to be better than everyone else.”

Pulliam began building a career in opera but after several years he quit. Not only was he Black but he was big. He had gained weight after giving up sports and was too heavy in the estimation of directors who didn’t think he could be convincing on stage or handle the physical demands of most roles.

“I got so tired of the BS of the industry,” Pulliam said. “I was young and hadn’t learned how to deal with rejection and also rejection that wasn’t based on your talent but your body size. It was nothing for a general director to say to me, with impunity, ‘You have one of the most beautiful dramatic voices I’ve ever heard but contact me after you’ve lost 50 pounds and I’ll give you an audition.’’’

Pulliam went to work for a collections agency and used his language skills to make calls in Spanish, French and Italian.

He got a job as a security guard at concerts and events, eventually starting his own personal protection firm.

Singing national anthem sparked rebirth

While working as a field organizer for Barack Obama’s presidential campaign in 2007 he rediscovered his voice. He was asked to fill in for the singer of “The Star-Spangled Banner” at a campaign stop. The singer got cold feet. Pulliam sang it, even though he had not sung anything for 10 years and “had no idea what would come out of my mouth.”

As soon as he heard “Oh, say can you see by the dawn’s early light,” he was surprised. He heard a more mature voice, a new timbre.

“The voice had grown in size and darkened in color. It had a burnished quality,” Pulliam said. “It piqued my interest. I thought it might be interesting to others. I wanted to find out where this voice belonged.

“I was a full lyric tenor when I stopped and more of a spinto tenor when I resumed singing.”

Pulliam realized he could sing an expanded repertoire.

“My late father always told me, ‘Son, your future is in your mouth,’” he said. “I decided to make a comeback.”

He dedicated himself to rebuilding his technique and in 2012 won a National Opera Association competition. He hit the audition circuit, shared videos, connected with agents and companies. Canio was the first role he was offered. Then Othello. In 2022, he became the first Black singer to sing the role of Radames in “Aida” at the Met — the first in its 240-year history. In 2023 he made his Carnegie Hall debut in “The Ordering of Moses.”

“For the role of Canio, I think Limmie’s body actually makes the story more believable because he makes the character vulnerable; he inspires compassion,” said Todaro, who has hired Pulliam in the past.

As for the casting of Pulliam and Piper Brown, performing together for the first time, Todaro says the chemistry between them is rare.

“It’s unusual because both have such velvety voices,” she said. “Limmie and Kearstin possess warmth and power. We talk about voices like we talk about painting. It’s the color of the voice, not the color of the skin that matters. These voices touch you at the core of your nervous system.”

New chapter for opera company

Pulliam and Piper Brown are here at an ideal time for the Florida Grand Opera as it embarks on a mission. Nearly 1,000 public school students attended the dress rehearsal for “I pagliacci.” FGO will stage a mini tour of “La bohème ” in schools in April.

“We want to catapult a 400-year-old art form forward and make it relevant in 2024,” said Tanya Byng, corporate and foundation development officer. “We want kids to see themselves in on-stage or back-stage roles. Without engagement with our current and future audiences, we are nothing.”

It’s a new chapter in FGO’s story, says Vidal-Duart, a Miami native and the daughter of Cuban immigrants who has specialized in turning around floundering businesses in her career. She got hooked on opera in her 20s and considers “I pagliacci” her favorite.

“We have such a great mix of races and cultures in South Florida, and people want to identify with what they see on stage,” she said, touching on plans to use digital technology to make opera a more immersive experience. “People are afraid of bastardizing opera but we’ve got to make it the cool thing to see. With Limmie and Kearstin in this production, we’ve taken a giant first step.”