Voices: I showed the Uvalde police response video to veterans. I traveled to the scenes of multiple mass shootings. This is what I learned

I was on a plane this week, on my way back from a two-week vacation, when the recently released Uvalde footage popped up on my phone.

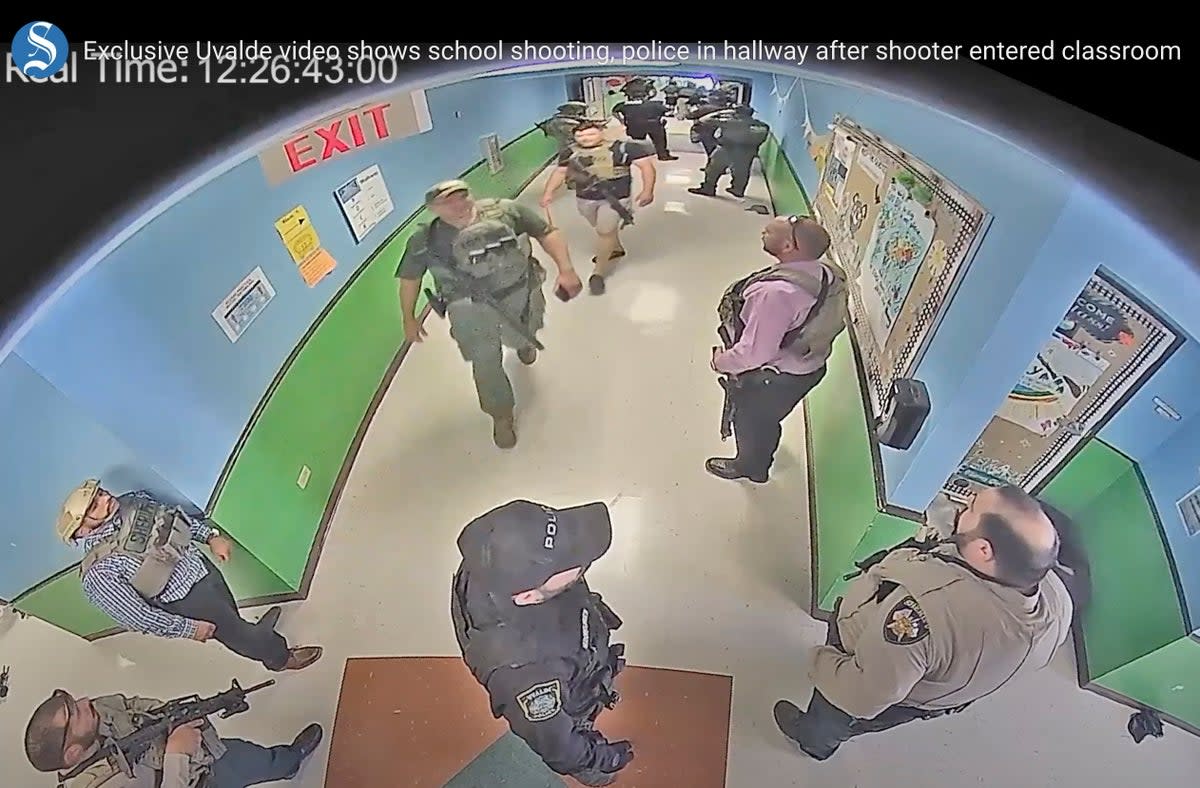

Sitting next to a young couple and their months-old baby, I watched the video while we waited on the runway. Onscreen, heavily armed response teams hung around, waiting, as nearly two dozen helpless children and teachers lay bleeding and dying just feet away. The fact that one cop even had time to casually spray some hand sanitizer while children were being slaughtered — some still calling 911 as those trained responders loitered in a hallway — really got me. I pulled my sunglasses down and began to cry.

Less than 24 hours later, I’d been standing in front of a memorial in Highland Park, Illinois. I was there on a reporting trip about the Fourth of July parade shooting — and I’d only just returned from reporting on a similar massacre at Robb Elementary School exactly seven weeks earlier. Highland Park and Uvalde had almost identical tributes outside them: The flowers, the magnified portraits, the chalk-written sidewalk messages, they were all the same.

“Remember there is more good than bad” read one note in Highland Park, an idyllic Chicago suburb, as people quietly paid homage to those lost at a Fourth of July parade. I’d been sent there, too, after families were senselessly slaughtered by a man with a gun. Is there really more good than bad? I thought to myself, when I saw that message. Driving down the Chicago highway, I’d passed a billboard for WearerTech — where a gunman had just shot three of his colleagues.

In November, I was in Wisconsin for the verdict in the trial of Kyle Rittenhouse, who was found not guilty in connection with the shooting deaths of two men. In May, I was in Uvalde, covering the murders of 19 students and two teachers at the hands of Salvador Ramos, who waltzed into a South Texas elementary school with weaponry and ammunition he’d recently bought for his 18th birthday. This month, I was in Highland Park where an atrocity had again been committed by an armed teen. These communities couldn’t have been more different. They varied in race, geography, socioeconomic status, political leanings, climate, everything. But they now had something terrible in common.

A journalist friend of mine, in a conversation after Uvalde and the subsequent Tulsa hospital shooting, was despondent. “Is this what we do now?” she said. “Just go from covering shooting to shooting?” We both felt the same way: It just keeps happening, again and again and again.

If you become a news journalist, you know what you’re signing up for (or you should, at least.) There will be accidents, tragedy, deaths, mayhem; it’s part of the job. You have to knock on doors and witness things that you’d rather not, but someone has to do it; there are serious social, ethical and historical responsibilities to reporting the news. You have to be resilient and realistic about what the job entails.

Law enforcement are supposed to be that way, too.

I come from a very conservative background. I’m the daughter of a Vietnam vet, from military stock on both sides of my family, and I’m extremely proud of that fact. I’ve lived in the Deep South, the Midwest, the West, and also Texas; I understand gun culture at this point, to say the least – even though I spent many of my adult years in Ireland, where most street cops aren’t even armed.

I showed the Statesman footage to my military friends – ex-US Army, ex-Irish Army, ex-British Navy. From infantrymen to officers, they were appalled. They couldn’t understand why no one stormed the classrooms earlier in Uvalde. They also couldn’t understand, on a wider scale, why anyone non-military needs assault rifles like the ones they used in combat – especially kept in a family home, easily accessible to anyone.

I never expected, 20 years ago, that I would be covering mass shootings with such alarming frequency. And after repeatedly turning up to these scenes, with their exponentially increasing death tolls, it’s hard to feel hope. A high-school classmate of mine just posted on social media about her experience of active shooter training. She works in a major hardware chain store. These days, it seems, everyone has to be trained about what to do when a mass shooter arrives with a military-grade weapon.

On the train back from the airport today, I was watching the doors. So many people jumped at the slight sound of any bang. I can’t even begin to imagine what the families of victims – everyone from schoolchildren to grandparents going about their daily lives – must feel.

Something needs to change, everyone agrees. But then it never does.