The Volunteer Moms Poring Over Archives to Prove Clarence Thomas Wrong

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In 2018, after a teenage gunman murdered 14 students and three faculty members at a high school in Parkland, Florida, Jennifer Birch, fearing for the safety of her own children, decided to join the fight against gun violence. “My kids were the same age, in high school,” she told Slate, “and it was enough to say: I have to do something now.” What Birch could never have anticipated is that five years later, she would find herself in the basement of a courthouse poring over 150-year-old county archives. Birch’s mission, as part of a volunteer force for the gun safety group Moms Demand Action, has been to identify Santa Ana, California, firearm regulations from the 1800s and earlier—all part of an effort to satisfy the Supreme Court’s increasingly preposterous whims about what’s necessary to prove a firearm regulation is constitutional.

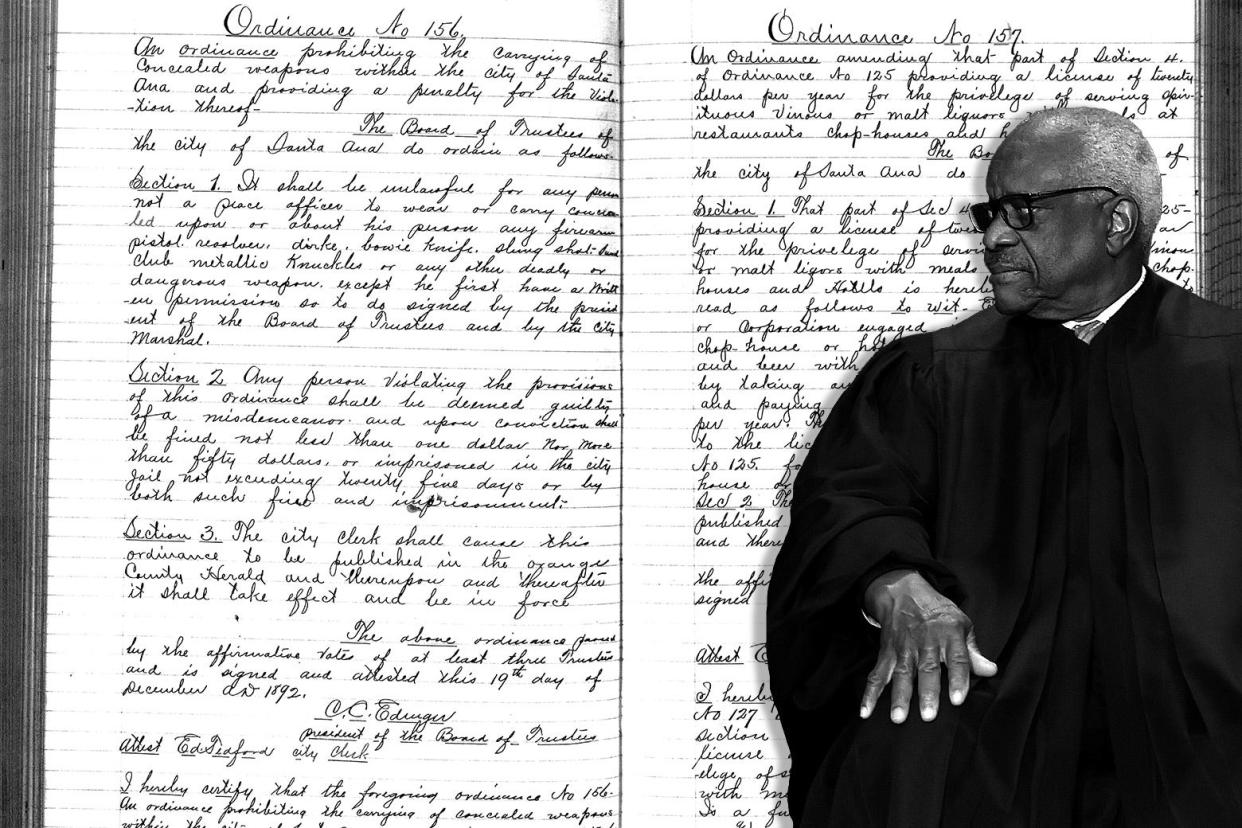

The archives Birch encountered were clean, dark, and mostly empty, with large tables upon which the archivist laid a series of fragile law books from previous centuries. Examining the delicate pages, Birch was surprised by what she found: Santa Ana prohibited the concealed carry of weapons, including guns, in 1892, while neighboring Anaheim followed suit in 1893. Orange County itself, in which both cities are located, had also prohibited concealed carry for well more than a century.

In 2022’s Bruen decision, the Supreme Court struck down bans on concealed carry and expanded upon the previous standard for determining the constitutionality of gun regulations, declaring that authorities had to find analogous gun laws that existed prior to 1900. Justice Clarence Thomas, writing for the court, found that before that date, concealed carry bans were not part of America’s history and traditions, and they were thus unconstitutional. Yet here, in a basement archive, Birch found evidence to the contrary, lost to history. And she had barely scratched the surface.

Birch is one of about 20 volunteers with Moms Demand Action, part of the gun safety group Everytown, who are scouring archives across the United States for historical firearm regulations. The project is far from academic. In Bruen, the Supreme Court demanded proof that a firearm regulation is rooted in “longstanding” tradition in the form of “historical analogues”—old gun laws that show how Americans “understood” the Second Amendment in the past. The historical record of firearm regulations, however, is far from complete. So motivated volunteers like Birch, a product designer by trade, are stepping in to fill the gaps. What they’ve found directly contradicts the Supreme Court’s conclusions.

While the academic research already relied upon by Thomas and other judges to strike down gun laws has been shaky at best, the stakes of attempting to satisfy the test he laid out could not be higher. For just one example, see next term’s big gun case, which asks whether the Second Amendment prevents the government from disarming people who are under a restraining order for domestic violence.

Until Moms Demand Action came along, attorneys looking to prove a gun regulation’s historic analogue have largely been outmanned and outgunned. According to Thomas, courts have no obligation to perform independent research in Second Amendment cases, or even satisfy themselves that they’ve amassed a fair and representative record. Rather, courts are “entitled to decide a case based on the historical record compiled by the parties,” and nothing else. The disparity in these cases between well-funded gun rights advocates and government attorneys—with little expertise and relatively low access to expert historians—means a court may strike down a gun law not because it’s unsupported by the record, but because government lawyers lacked the time, knowledge, and resources to dig up analogous laws from the past.

Volunteers like Birch want to change that, one archive at a time. Bita Karabian, a friend and co-volunteer, got involved with Moms Demand Action after the Uvalde massacre. “I realized we aren’t safe at school, at the grocery store, at a movie theater,” she said. A lawyer in her day job, Birch initially focused on lobbying the Legislature to “fix the hole that Bruen punched in California’s gun safety laws.” Once Birch and Karabian took on research roles, though, they quickly grew attached to the work. “I was interested in learning more about the history of where I live,” Birch explained. “As I started to go through the archives, I got more inspired.” The two made connections with state archivists and city clerks throughout Orange County, learning to parse the “fancy cursive handwriting” of the 1800s. Some city ordinances weren’t even indexed, forcing Birch and Karabian to leaf through the longhand lawbooks page by page, wearing special archival gloves.

There is a certain thrill in the hunt. “After the first few finds, I was like, ‘Whoa,’ ” Birch told me. “There was so much there.” Over and over again, Birch and Karabian found the same thing: strict limits on the use and possession of firearms, dating back at least to the 1850s, that belie Bruen’s vision of a 19th-century Wild West where the right to bear arms was almost never infringed on. The regulations uncovered were consistent as to weapons and across cities throughout Orange County, one of the more conservative counties in the state. “Many of these limitations were enacted shortly after cities were incorporated as part of their very first batch of laws,” Karabian said. “They were always framed as commonsense safety precautions.” She was surprised: “I thought: ‘Wait a minute—every city in conservative Orange County had a prohibition on concealed carry dating back to their earliest days?’ ”

These regulations covered the gamut: “Almost every city had prohibitions on concealed carry,” Karabian said. Not just license requirements, she noted, but outright bans: “One of their first acts was to make sure that people are safe, which meant not carrying concealed weapons.” Other ordinances outlawed the firing of any gun within the city. California cities also required gun owners to store gunpowder safely, and restricted the amount of it that a person could store at one time. These laws are analogous to modern-day regulations of ammunition, like requirements for safe storage and bans on high-capacity magazines—regulations that are under attack in the courts right now. (Many of the most lethal mass shootings are carried out with high-capacity magazines.)

Volunteers in other states report the same thing. (Everytown is compiling a list of their discoveries; the organization shared a draft with Slate and allowed us to share individual findings, but asked us not to publish the entire list—currently at 159 laws—because it remains incomplete.) The volunteers note every gun-related law they come across, whether it loosens or tightens access to firearms, but the trend is overwhelming: In the 18th and 19th centuries, cities and states were far more concerned with keeping guns out of people’s hands, and away from public spaces, than with guaranteeing a right to bear arms.

A representative sampling: In the 19th century, the concealed carry of firearms was expressly forbidden in Memphis, Tennessee; Jersey City, Hoboken, and Plainfield, New Jersey; Chicago, Illinois; New Orleans, Louisiana; Olympia and Wilbur, Washington; and Denver, Colorado. More than 50 local governments outlawed the firing of any weapon within city limits. About 30 localities restricted or outlawed the storage of gunpowder, including Santa Ana. A dozen localities limited, heavily taxed, or banned shooting ranges. (In 2017, a federal appeals court struck down a Chicago law that restricted—but did not outlaw—shooting ranges within the city, finding no “history and legal tradition” to support it.) More jurisdictions banned guns in private establishments; for instance, an 1817 ordinance in New Orleans barred citizens from carrying weapons into a “public ball-room.” (In January, a federal judge blocked a New Jersey law that banned guns in bars, restaurants, and entertainment venues, finding that it was not supported by “the nation’s historical tradition.”)

These findings are the result of about one year’s work by 20 volunteers. The numbers increase significantly when laws from early decades of the 1900s are included. In Bruen, however, Justice Thomas declared that all laws enacted after 1900 are not constitutionally relevant, because they do not “provide insight into the meaning of the Second Amendment.”

This arbitrary cutoff hints at a broader problem for Everytown’s project: It is unclear whether judges who avidly support a sweeping right to bear arms will care about evidence that contradicts their beliefs. The record of these judges so far is uninspiring.

Moreover, Thomas’ opinion in Bruen displayed a great talent for dismissing every piece of evidence that clashed with his favored outcome. For example, in the 1800s, many Western territories implemented stringent restrictions on firearms; some, like Idaho and Wyoming, prohibited the public carry of any firearm in all municipalities. Yet Thomas dismissed the importance of these laws, reasoning that they were “transitional” measures that did not reflect the national “consensus” or “tradition.” Such “confounding” logic, as one federal judge described it, might allow Thomas and other like-minded judges to wave away any piece of evidence that volunteers like Birch and Karabian are able to put in front of them.

This selective exclusion, and many other slippery aspects of Thomas’ analysis in Bruen, may prompt pessimism about whether the Everytown database will serve any real purpose or change any minds. But Jacob Charles, who served as the executive director of the Center for Firearms Law at Duke University School of Law, sees real value in the effort. Few scholars have paid keener attention to the post-Bruen fallout than Charles. The center is compiling a repository of historical gun laws that’s approaching 2,000 entries; the findings are meant to assist lawyers and judges, though it is also open to the public. Despite his skepticism of the Bruen test, he saw real value to Everytown’s work.

“In my experience reading lower court judges implementing Bruen’s test so far,” Charles told me, “most seem to be trying to conscientiously apply the new test and struggling with how to reason analogically across time to any number of historical regulations. For most of them, I think, they will welcome additional historical materials to work with, but continue to struggle with understanding what to draw from them.” At the Supreme Court, however:

I think there’s reason to doubt that additional historical evidence will make too much of a difference. If Bruen is any indication, there are several justices ready to dismiss evidence showing restrictions on the right and who will focus very minutely on any discernible differences between modern and historical laws.

Even if volunteers like Birch and Karabian cannot change any of the justices’ minds, in other words, their research may have a real impact in the lower courts, where most Second Amendment cases are decided. For example, the federal judiciary is grappling with the constitutionality of laws that limit the locations of shooting ranges, restrict concealed carry in public and private venues, disarm people convicted of illegal substance use, and ban assault weapons, high-capacity magazines, and other unusually dangerous weapons. Volunteers with Moms Demand Action have already found historical analogues that support all of these modern laws, and their work has just begun.

There is value, too, in documenting the truth at a time when jurists like Thomas are embracing brazen falsehoods, and transforming them into the law of the land. Future generations, and future Supreme Courts, may see this historical evidence as a justification to roll back or overturn decisions like Heller and Bruen that hinge on bogus history. At a bare minimum, setting the record straight helps the public understand that Justice Thomas is endangering people’s lives on the basis of a lie. The fight for gun safety laws follows a long and legitimate American tradition. It is the battle against gun safety that seeks to transform the Bill of Rights into a suicide pact.