Volyn (Volhynia) 1943: The future in labyrinths of the past

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Forced reconciliation is a road to nowhere. A one-sided "Volyn Nuremberg" is impossible in practice. Ukrainians and Poles need to remember that the anniversaries of this anti-Polish action will be followed by another day, and they should choose their words carefully to avoid making it impossible to communicate the day after.

The Ukrainian poet and writer Serhii Zhadan aptly noted in one of his works that the past does not just hang over us; to a great extent it defines our future; with its vagueness, uncertainty, and incompleteness, when all is said and done; the past is here – it pulls us down like ballast and fixes us to the spot like an anchor.

Yale University professor Timothy Snyder has pointed out, with good reason, that history – whether it's truthful or not – often has a paralysing effect. This is an unsettling conclusion.

This is especially the case with those chapters of the past that are sensitive and cause heated debate within societies and between nations. Ukrainians and Poles are united and at the same time divided by several centuries of rather tumultuous history, which has seen periods of cooperation and mutual understanding as well as bitter conflicts.

The issue of Ukrainian-Polish conflicts has been quite extensive, even in the 20th century. There are many chapters in the shared Ukrainian-Polish past that are still being fiercely debated and argued over by historians, journalists, politicians and public figures. However, we can safely say that most of them revolve around Ukrainian-Polish rivalry during World War II.

The difference in the Ukrainian and Polish positions is reflected in their approaches to exploring the events in Volyn. While Ukrainian authors primarily try to focus on identifying the roots of the conflict between Ukrainians and Poles during the war years, stressing the impossibility of considering what happened in Volyn outside of the historical context, as one of the links in a chain, Polish authors focus on the events of 1942-1944.

In Poland, the Volyn tragedy is seen as an independent phenomenon, lacking historical context. The exclusive focus on 1943 ignores the background leading up to the events of that year and the massacres of civilians in 1944-1947. The Ukrainian side of the argument stresses the reciprocal nature of the conflict, whereas the Polish side emphasises its one-sidedness, focusing entirely on Polish victims.

Either way, two visions of what happened during World War II have emerged, as if two truths have come to light, and the war over history between Ukrainians and Poles is now as uncompromising as the Volyn tragedy itself.

Volyn as a node

To reap a harvest, you must first sow the field. No phenomenon is born out of nowhere; it has reasons behind its existence, often more than one. The most reasoned and unbiased approach is to see inter-ethnic conflict as a chain of cause and effect, immersed in the darkness of ages, which should be traced dynamically.

Professor Bohdan Hud, a professor in Lviv, believes that the starting point for the incitement of hostility between Ukrainians and Poles in Volyn was the end of the 18th century, when the Russian government, having seized the territory of the Right Bank of Ukraine [land west of the Dnipro River, including Volyn] in 1793, began to apply the ancient Roman principle of divide et impera (divide and rule) to remarkable effect.

Polish uprisings in the 19th century undermined the influence of the Polish nobility in Volyn - their focus had shifted to the west of Ukraine after they lost their "Arcadia" in Right-Bank Ukraine to the Russian empire - and ensured the depolonisation of Ukraine. Despite this, in Polish public opinion this did not involve abandoning the famous slogan "od morza do morza" ("from sea to sea") as a state-building programme. ["Od morza do morza" is a Polish nationalist slogan within the Polish analogue of Panslavism, an ideological attitude implying that a federation of peoples under Polish rule should extend "from sea to sea", i.e. from the Baltic to the Black Sea.]

Volyn Province as part of the Russian Empire. 1911

For this reason, Poland and the Poles were portrayed as "aliens" and "exploiters" in the popular consciousness of Ukrainians in Halychyna (Galicia) and Volyn in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. These images were later used by ideologues to quickly engage peasants in the Ukrainian nation-building process. Centuries-old antagonism on social grounds - "Pole" (synonymous with "lord") and "Ukrainian" (synonymous with "serf") - that had caused strife between Ukrainians and Poles evolved into national antagonism.

This was the baggage of stereotypes Ukrainians and Poles were carrying as they faced World War I and the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian and Russian empires. At that time, they had the chance to create sovereign states. However, instead of reaching an understanding in the interests of both nations and finding compromises, Ukrainian and Polish politicians chose confrontation.

One of its most obvious manifestations was the Polish-Ukrainian war for Halychyna and other western Ukrainian lands in 1918-1919. When Poles talk about Volyn, they avoid mentioning what happened before the Volyn tragedy, in 1918-1919, in 1938, and so on. And therefore it seems, as Ukrainian historian Yaroslav Hrytsak has noted, that this "massacre" came out of nowhere, purely because there were Ukrainian nationalists; and this is dangerous.

Defeat in the national liberation struggle of 1918-1921 was firmly embedded in Ukrainians’ collective and individual consciousness, and they perceived the reason for the failure to be the newly formed Polish state, where Ukrainians were a substantial ethnic minority. Moreover, they constituted the majority in the Volyn Voivodeship, accounting for almost 70%, while the Poles were a minority of 16%.

Ukrainian historians believe that the main reason for this was the policy of the Second Polish Republic towards ethnic minorities, especially Ukrainians. The policy of the ethnic assimilation of Ukrainians involved establishing military settlements in the "Kresy Wschodnie" (Eastern Borderlands): Polish army veterans were resettled in Volyn and given relatively large plots of land - land being something of which most of the local population had very little. Notably, the Volyn Voivodeship had the most military settlements (432).

Number of military settlements by voivodeship, showing that Volyn has 432

The number of such settlers is even more striking: roughly 4,500 out of a total of 11,000 were resettled in Volyn.

Over the course of twenty years, 200,000 ethnic Poles moved to rural Volyn, and a further 100,000 settled in cities and worked as government officials and law enforcement officers. This, in turn, was resented by the Volyn peasantry and turned them against the Polish state.

Number of settlers by voivodeship (4,481 in Volyn)

This policy included the "pacification" of Ukrainians in Eastern Halychyna and Volyn in the 1920s and 1930s, a state-organised terror against the Ukrainian population that caused such an outcry internationally that it was discussed at the League of Nations. This convinced the peasants of Volyn, Eastern Halychyna and Kholmshchyna [a historical and geographical region of Rus', located to the west of the middle of the Western Buh River] from their own experience that the Second Polish Republic was an alien state to them.

One act of revenge for "pacification" was the assassination of Polish Interior Minister Bronisław Peracki on 15 June 1934 by Hryhorii Matseiko, an Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) fighter. Polish President Mościcki responded by ordering a concentration camp for political prisoners to be set up in the town of Bereza Kartuzka in Beresteishchyna [a culturally and ethnically Ukrainian region in Western Polissia, most of which is in the modern-day Brest Oblast of Belarus]. This obviously did nothing to improve Ukrainian-Polish relations.

The Polish concentration camp in Bereza Kartuzka as it is today

On top of this, we can also add "revindication" – the targeting of Orthodox churches in Kholmshchyna and Southern Pidliashshia [Podlachia, a historical, ethnically Ukrainian region now in southeastern Poland – ed.] by the Polish government, with hundreds of churches destroyed or transferred to the Roman Catholic Church. Given that faith was of paramount importance to the people of Ukraine’s West, such actions by Polish border guards, army and police certainly contributed to the escalation of the Ukrainian-Polish conflict during World War II.

Therefore, the conflict that had been raging on between Ukrainians and Poles for centuries had to find an outlet. And when the "macro" World War II broke out, it sparked the Ukrainian-Polish "micro-war" against this backdrop, especially given that the main actors – the Soviet Union and the Third Reich – had an interest in fuelling it.

An Orthodox church destroyed during revindication in the village of Kryliv

However sad it may be to state this, we must admit that conflict between Ukrainians and Poles during World War II was impossible to avoid.

Of particular importance is the context of 1943, when the Polish Home Army [Armia Krajowa, the dominant resistance movement in German-occupied Poland during World War II] and the Polish government-in-exile in London attempted to secure Volyn, Eastern Halychyna, Kholmshchyna and Pidliashshia as part of the Polish state to be recovered after the war at any cost.

The exaggeration of the number of attacks on Polish settlements became a false premise from which it was concluded that a large-scale operation was going on throughout Volyn. This led to the conclusion that there had been an order stipulating the complete extermination of the Polish population, and thus genocide or, at the very least, ethnic cleansing.

The overstatement of the number of victims in the Polish population is logical in the context of two trends characteristic of Polish society: the stereotype of the brutality of Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA) units (and thus of Ukrainians in general, as evidenced by the recent use of the term ukraińskie ludobójstwo – Ukrainian genocide), and the perception of their own nation as victims.

"The forgotten genocide": The weekly Do Rzeczy reminds Poles who Ukrainians are – moustached, axe-wielding church-burners

What is perhaps most striking is that the statistic of 100,000 murdered Poles was not the result of many years of archival research, painstaking victim counts, or conclusions drawn by prosecutors from the Institute of National Remembrance as part of an investigation, but primarily the outcome of agreements reached with Kresy (Borderland) communities.

The West of Ukraine found itself at the epicentre of geopolitical games between European players. The USSR took control of these lands under the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact [a non-aggression pact between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union that partitioned Eastern Europe between them]. It was of the utmost importance for the Soviet Union that they should be consolidated within its realm de jure and de facto. Polish interests demanded that they be given back to Poland. Ukrainian politicians saw these territories as Ukrainian and wanted to take advantage of World War II in the struggle for an independent and united Ukrainian state.

A map of Poland signed by Stalin and the Nazi German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop showing the revised border between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union following the joint aggression in 1939

A supporting actor

One way or another, the issue of Russia's role in the growing tension in contemporary Ukrainian-Polish relations occasionally arises during the debate over Volyn. Whether we like it or not, Russian influence is present in Ukrainian-Polish dialogue. This factor should not be overlooked, reducing all troubles and misunderstandings to the results of intelligence operations and paid-for actions.

As Timothy Snyder has observed (one may not always agree with him, but in this case it's hard to argue), Russia relies on Polish-Ukrainian conflicts. He adds that since this is a known fact, the case of the Volyn atrocity should be primarily the subject of historians' work, and mutual tolerance is essential for this.

We need to remember that Russia is active in both Ukraine and Poland. It has agents of influence in both countries and benefits from destabilising Ukrainian-Polish relations, so it will keep working to incite hostility, using historical politics to do so.

An analysis of texts that mention the Volyn tragedy has shown that it is an element of the hybrid war being waged by Russia against Ukraine and Europe as a whole. I’m not going to dwell on journalism and pseudo-academic writing whose authors provide suitable information with assessments to match (or worse, content from separatist websites).

I would like to mention two other aspects. The first is the ongoing agitation of Ukrainian and Polish societies by acts of vandalism at memorial sites: Hruszowice, Guta Peniacka, Wierchraty and others. The Ukrainian Cyber Alliance has proved that these were financed by the Russians (and not only in Poland).

A vandalised monument on a UPA grave in Poland

The second is the fact that this is a topic Russian officials talk about. In this regard, it is worth mentioning the speeches of Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov and the fact that Vladimir Putin himself, in an article for the American magazine The National Interest, brought up the subject of Volyn, along with Babyn Yar [the site of mass executions of civilians and Soviet prisoners of war, Jews and Gypsies, etc. by the Nazis – ed.] and Katyn [a series of mass executions of nearly 22,000 Polish military officers and intelligentsia prisoners of war carried out by the Soviet Union – ed.].

This makes unbiased research into the Ukrainian-Polish confrontation during World War II a matter of national security. And both Kyiv and Warsaw need to understand this. Unfortunately, even though some analysts understand this, there is no understanding at the level of senior officials. That is why it needs to be acknowledged that neither Ukraine nor Poland has done their homework.

Time for a fresh start, or just keep going?

It's unlikely that historiography can ever be entirely separated from politics. Historiography depends in one way or another on making judgements. Therefore, it is at least subconsciously influenced by the author's civic position, even if not by the politics of remembrance.

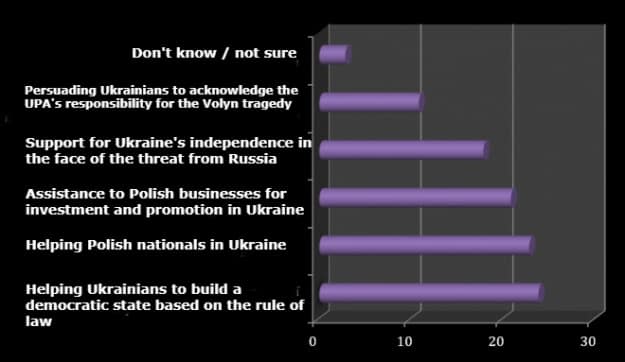

The number of Polish associations related to history, including the large percentage of references to the Volyn tragedy (almost half (44%) of those related to history and politics), is notable. It is no wonder, then, that when respondents to a 2020 opinion poll were asked what the objectives of Poland’s policy towards Ukraine should be, 11% said that Ukrainians should be urged to acknowledge the UPA's responsibility for the Volyn massacre.

Many Poles see the history of the OUN and UPA as exclusively about killing Poles, while Ukrainians perceive UPA soldiers primarily as fighters against communism.

What is worth highlighting and emphasising is the experts' conclusion that we need to learn as much as possible about the historical truth and dramatic past of Ukrainian-Polish relations as a necessary step towards reconciliation between these neighbouring peoples. And what is crucial is that the conclusions do not necessarily have to be identical, but they must be impartial.

The pursuit of an answer to the perennial question of "Who started it?" does not really make sense. Exchanging mutual accusations and measuring the weight of offences is a road to nowhere. After all, following Ivan Patryliak, a Ukrainian scholar and a specialist in the history of Ukrainian nationalism, let's ask a rhetorical question: what is more horrific - a brutal, bloody slave uprising, or the hundreds of years of slavery that preceded it; a rebellion by locals in the Congo, or the methods the Belgians used to rule over them; French policy in Algeria, or what Algerian rebels did to French settlers afterwards?

One thing is clear: the Volyn debate will keep going for a long time. It’s not only about the past, but also the moral maturity of Ukrainian and Polish societies. In any case, we should agree that we have to come to terms with the past for the sake of the future.

A compromise cannot and should not be based on sanctions, moratoriums, ultimatums or unilateral concessions, but on understanding and accepting the other side's views. This can be achieved by way of cooperation through existing institutions and forums. Forced reconciliation is a road to nowhere.

A unilateral "Volyn Nuremberg" is not only impossible in practice: it will lead volens nolens to a recurrence of the Armenian-Turkish deadlock in Ukrainian-Polish relations. Ukrainians and Poles need to remember that the anniversaries of this anti-Polish action will be followed by another day, and they should choose their words carefully to avoid making it impossible to communicate the day after.

By Oksana Kalishchuk, Professor of History, Lesia Ukrainka Volyn National University

Translation: Artem Yakymyshyn

Editing: Teresa Pearce