From ‘votes for women’ sashes to pussyhats, fashion makes political statements

Jayna Zweiman wasn’t trying to make an overt political statement when she came up with the idea to wear a pink knit hat the day of the 2017 Women’s March. She just wanted to feel connected.

Zweiman, 41, is a Los Angeles-based architecturally trained artist. In 2017, she was recovering from a serious back and neck injury that was going to prohibit her from attending the Women’s March, set to take place the day after Donald Trump was sworn in as the 45th president.

“Maybe we could make a hat?” she mused to her friend Krista Suh, a screenwriter.

“We kept coming back to the question, how do we get all these women who care about women’s rights to participate if the march itself is out of reach for a specific reason?” Zweiman says. “It became, let’s create a process where we can extend the march.”

Weeks later, knit and crocheted pussyhats — patterned with tiny kitten ears and named in an effort to reclaim a word often used in a derogatory manner — helped create a pink wave from coast to coast, as millions of women took to the streets to protest in furious response to Trump.

One month later, on the Milan Fashion Week runway, Angela Missoni of the legendary brand ended her fall 2017 show with glamorized versions of the pussyhats. In Los Angeles, Zweiman gasped.

“It was really, really trippy,” she recalls.

Missoni’s pussyhats might have caught the general public off guard, but those paying attention to history were not surprised.

For decades, women have been using fashion as a form of political protest, dressing and styling themselves in certain ways to convey certain messages. From the earliest days of the suffrage movement, when women used specific symbols and colors to emphasize their message, the echoes roll on through contemporary times. Pink pussyhats walking the runway during fashion week is hardly the only example.

“Fashion is about identity politics, period, for everybody,” says Vanessa Friedman, the chief fashion critic at The New York Times, who has worked in fashion criticism for more than 15 years. “Designers, when they’re doing their jobs, reflect changes in the world around them and create clothes that speak to that. That’s why people buy them — most people don’t actually need new clothes.”

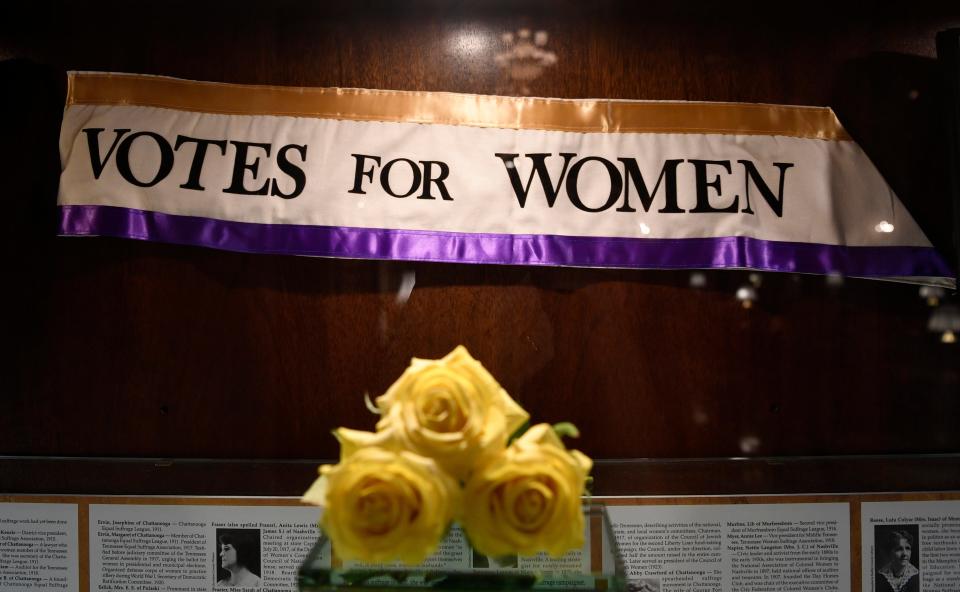

America commemorates this August the 100-year anniversary of the ratification of the 19th Amendment, which granted most women the right to vote (many women of color still remained practically, if not legally, disenfranchised). It was a long, dogged fight, punctuated by peaceful protests, hunger strikes and lots of “Votes For Women” sashes.

Raissa Bretaña is a fashion historian who teaches at the Fashion Institute of Technology in New York City whose master’s thesis explored fashion and the women’s suffrage movement. She says it’s important to recognize the obvious themes, like the suffragists' repeated use of white, purple and yellow. There are also some more subtle themes to analyze, like when suffragists’ "rehabbed” their images in the first decade of the 20th century.

As the fight for women’s rights was intensifying, American suffragists worked to tidy their images. In England, where women were granted the right to vote in 1918, Bretaña says, “the idea of the suffragist was of a dowdy shrew, a nag who dressed poorly, who was so dedicated to the cause, she couldn’t be bothered to look respectable.”

In response, American suffragists made a conscious effort to adopt “fashionable dress so they could be seen as ‘respectable’ members of society who also happen to be campaigning for the right to vote,” Bretaña explains.

And make no mistake that shifting to a more “respectable” dress was typically only available to wealthier white women, a purposeful distinction in a movement that often pushed women of color to the sidelines.

Each official suffrage color served a purpose: yellow was a nod to sunflowers, the state flower of Kansas, where the first suffrage referendum was held. Purple stood for dignity; white for purity. Then there was the official suffrage hat: shallow crown, wide brim with a yellow, purple or white ribbon. Together the sashes and hats created a uniform, donned by soldiers in the fight for equal rights.

Put simply, much of fashion history is actually social history, says Bretaña. And it’s no mistake that as women started to reject corsets and embrace freedom of movement, they were also embracing freedom of thought.

Speaking through clothing didn’t stop when women were finally allowed access to the voting booth, either. Bretaña points to other examples where women chose to make a statement without ever opening their mouths.

Around 1910, the time the suffrage movement really took off in the U.S., hemlines were starting to creep up, exposing ankles (scandalous!) just as women were starting to roam their towns without chaperones (unseemly!).

It was radical, Bretaña says, and maybe even downright brazen, to march in the street making a spectacle of oneself. To do so while toting a “Votes For Women” banner caused even more of a stir.

Then, women began to wear pants!

“For centuries, women had used corsets and hoop skirts to shape their bodies,” Bretaña says. “Then, with the dawn of modern fashion they were allowing their bodies to shape the clothing … (trousers) became kind of the emblem of this very forward-thinking, modern woman.”

Iconic Hollywood leading lady Katharine Hepburn — whose mother was the head of a Connecticut suffrage organization — was famous for wearing pants long before they were considered acceptable, much less fashionable.

Timeline: Women’s suffrage was a 70-year battle

5 movies, TV shows to watch to mark the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment

Equal Rights Amendment: Will women ever have equal rights under federal law?

In the World War II era, fabric was rationed, so skirts got considerably shorter. A skirt past the knee communicated that you were likely hoarding fabric, which came with its own set of politically-tinged questions and accusations. In 1947, when Christian Dior debuted haute couture in Paris and featured a collection with lots of full, long skirts “he was met with protesters, because that dress was suddenly seen as regressive,” Bretaña says.

More than 20 years later, as the women’s movement captivated America, it wasn’t the burning of bras that made a statement, but rather the millions of women who donned miniskirts. Putting that much of your body on display was another way of proving you were indeed liberated — whether or not the patriarchy wanted you to be.

More recently, it’s been pink pussyhats in the streets and on the runways, and Fashion Week T-shirts emblazoned with various political messages: “We should all be feminists”; “I am an immigrant”; “People are people”; “Revolution has no borders” and more.

Fashion can and will always be used to convey political messages. Zweiman, the pussyhat creator, finds comfort in this. She thought of the pussyhats as a way to make her feel connected to something bigger. And isn’t that what politics is about anyway, coming together in the name of a cause?

Truly everything is political, she says — and your body is merely another type of billboard to display your message.

More coverage

Women of the Century: They didn’t succeed despite adversity, but often because of it

50 states: Learn about notable women from every state

Who is your Woman of the Century?: Let us know

Recognizing women past and present: See all of our coverage

19th Amendment coverage

In fight for 19th Amendment, suffragists saw Tennessee as last hope and worst nightmare

Women suffragists persisted for 70 years to win the right to vote in 1920

Famous women's suffrage speeches come to life in augmented reality

‘Be a good boy’ and vote for suffrage: How a mother’s note carried the 19th Amendment

‘Sisters helping sisters’: The surprising role religion played in the women’s suffrage movement

Tennessee suffragists changed history ‘without firing a shot’

Think you know everything about women’s suffrage? Here’s the history to unlearn

Equal Rights Amendment: Will women ever have equal rights under federal law?

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Suffragists and modern women used fashion as political protest from pussyhats to sashes