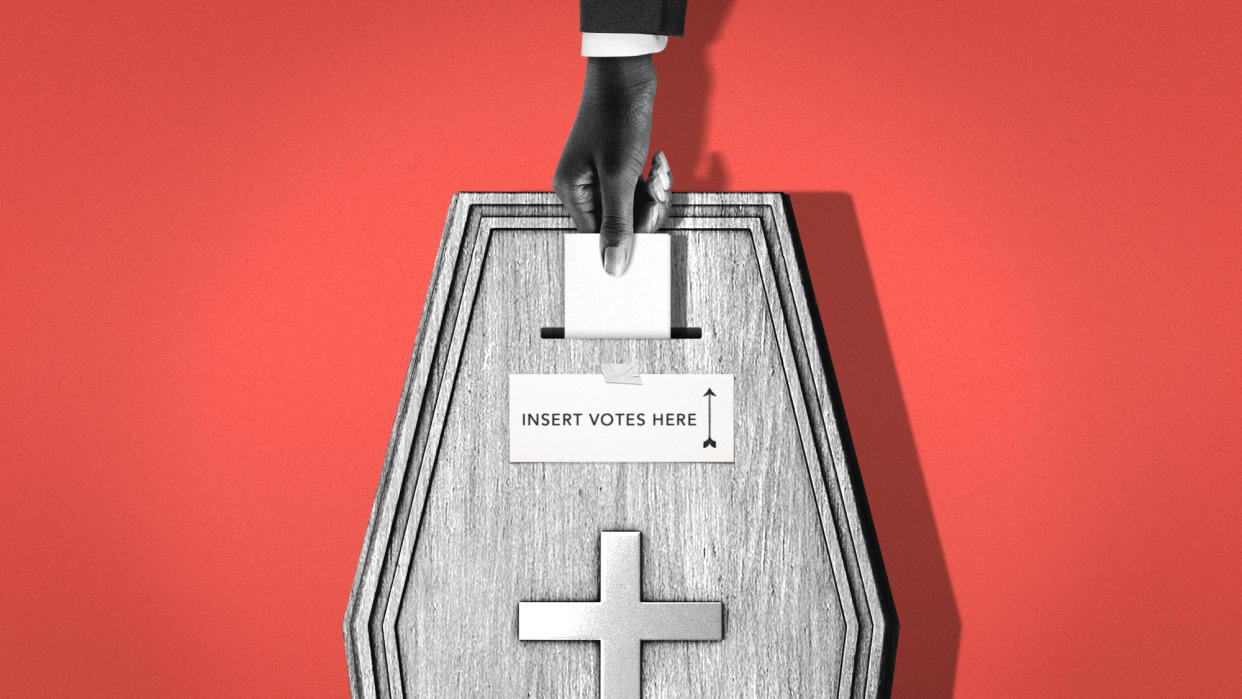

Is the Voting Rights Act nearly dead?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The Voting Rights Act is a landmark law of the Civil Rights Era — a key part of Martin Luther King Jr.'s legacy — and it's in big trouble. Again. A federal appeals court on Monday voted to "drastically weaken" the law, The New York Times reported, saying that only the federal government can bring challenges to racially discriminatory state and local election rules under the act, a decision that would "effectively bar private citizens and civil rights groups" from filing lawsuits to protect voting rights.

Why is that a big deal? Because, as election law attorney Marc E. Elias explained on X, there have been 182 successful cases brought under the VRA over the past four decades — and only 15 of those were brought by the Department of Justice. Monday's ruling is "quite a seachange in the way that everyone — Congress, the courts, plaintiffs, and even defendants — have thought" about how the law would be enforced, ACLU's Sophia Lin Lakin told Bloomberg Law. For the appellate judges, though, the reason for their ruling was simple: "The Voting Rights Act lists only one plaintiff who can enforce [the provision in question]: the Attorney General," Judge David R. Stras wrote for the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals in St. Louis.

That decision "could end voting rights," Adam Serwer argued at The Atlantic. The law, passed in 1965, "made America a true democracy for all of its citizens." Throughout its history, private citizens have used the law to challenge racial discrimination at the polls. Monday's ruling "would effectively outlaw most efforts to ensure that Americans are not denied the right to vote on the basis of race."

What the commentators said

"It's hard to overstate how important and detrimental this decision would be if allowed to stand," Rick Hasen wrote at Election Law Blog. The "vast majority" of claims to enforce the racial discrimination provisions of the Voting Rights Act are brought by private plaintiffs, because the Department of Justice has "limited resources." The attorney general probably won't be able to fill the gap. "If minority voters are going to continue to elect representatives of their choice, they are going to need private attorneys to bring those suits."

But the decision is actually quite narrow, Margot Cleveland countered at The Federalist, "solely a question of statutory interpretation." Yes, the law is "a go-to tool to strike down state laws regulating voting and congressional maps." But courts had mostly "sidestepped" the question of who gets to sue, and simply assumed that private groups and individuals have standing. That's not what the law says. "While Congress could have authorized private individuals to sue, it had not."

Maybe they should. "When the government discriminates against people, they should have a right to fight back in court," Paul Smith argued for the Campaign Legal Center. Private lawsuits, the center said, "are critical to ensuring that voters of color are able to secure fair maps and make their voices heard."

What next?

Monday's ruling "seems certain to instigate a new voting-rights showdown as the nation heads into a presidential election cycle," Joan Biskupic wrote at CNN. It's also a significant example "of former President Donald Trump's influence over the federal judiciary." Judge David R. Stras was one of Trump's first appellate court appointees, and issued a ruling that Justices Clarence Thomas and Neil Gorsuch — Trump's first higher court nominee — seemed to invite in their previous opinions in elections cases.

Those justices will almost certainly get a chance to weigh in. Monday's ruling "tees up" a likely fight at the Supreme Court, The Washington Examiner reported. And it could have a big impact on the 2024 presidential election. Forbes noted that for now the ruling only applies to eight states covered by the Eighth Circuit. If SCOTUS hears the case this term, though, it could become "significantly harder to challenge voting rules nationwide" in the runup to the likely Joe Biden-Donald Trump rematch.