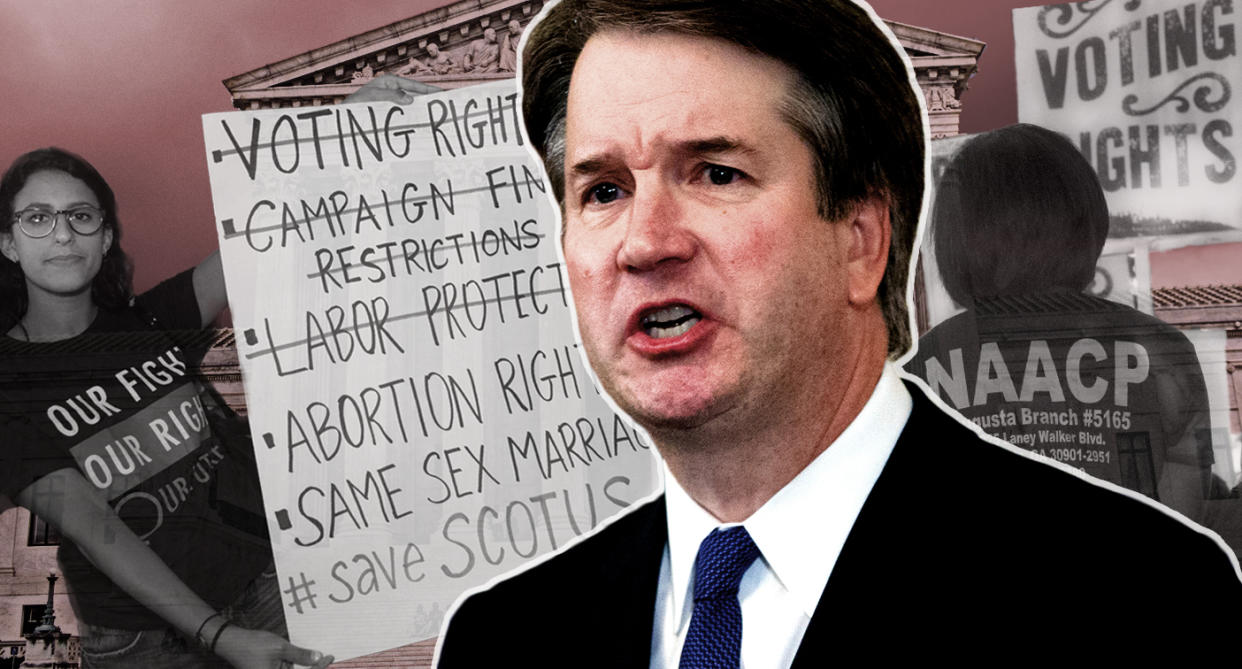

Voting rights advocates wary of Kavanaugh's nomination to Supreme Court

The nomination of Brett Kavanaugh, a federal appeals court judge, to the Supreme Court drew instant criticism from women’s rights groups that consider him a potential fifth vote to curtail or overturn the right to abortion. But ahead of his confirmation hearing — with midterms and the 2020 presidential election looming — voting rights advocates, alarmed about the trend toward disenfranchising young, poor and minority voters, are joining the #SaveSCOTUS and #StopKavanaugh movements.

“We had a really bad term in terms of voting rights,” said Kristine Lucius, executive vice president for policy at the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights, a key backer of the Save SCOTUS campaign. “And it really shows how the court has shifted against access to the ballot. My sad prediction is it could get even worse.”

“Kavanaugh’s track record on democracy raises serious concerns,” said Chiraag Bains, director of legal strategies for public policy organization Demos. “A Justice Kavanaugh on the Supreme Court could set us back when it comes to voting rights.”

The nomination of Kavanaugh to replace retiring Justice Anthony Kennedy came just two days before the Supreme Court ruling in the Ohio voter purge case, Husted v. Randolph Institute. The 5-4 decision upheld Ohio’s mass purges of “inactive” voters from the registration rolls, reversing a lower court finding that the policy violated the National Voter Registration Act (NVRA), enacted in 1993 to make it easier to register to vote and maintain registration.

Ohio’s voter purge followed the state’s policy: Registered voters who didn’t vote for a two-year period were sent notices. If, in the following four years, they failed to respond, vote or engage in any voter activity — like updating their registration or address — their names were removed from the rolls and they were required to reregister to vote.

“There are many reasons people choose not to vote in any given federal election,” said Lucius. “And the notion that you would respond to a piece of paper that you receive in the mail, probably folded in with all your junk mail, doesn’t seem like it really values the importance of voting rights.”

The challenge to the state’s procedures relied on a provision of the NVRA that says the failure to vote in previous elections cannot be the sole basis for purging people from the rolls. The Supreme Court decision held that Ohio’s multistep purging process did not violate federal laws.

Two weeks after the Ohio ruling, the court dealt another setback to voting rights groups and civil rights organizations in Abbott v. Perez. In that case, the high court reversed a lower court’s findings that a 2013 Texas redistricting plan was “tainted” by bias and intentionally discriminated against Latino and African-American voters to dilute their voter strength. Holding there was insufficient evidence proving “discriminatory intent,” the Supreme Court ruled 5-4 that just one of the many districts was racially gerrymandered. But civil rights advocates argue that proving “intent” is nearly impossible.

“Discrimination in all spheres, including in voting, is usually done by stealth,” said Bains. “When people intentionally discriminate based on race, they don’t usually tell you they’re doing it. Folks who are discriminating for whatever reason, whether animus against people of a certain race or to gain partisan advantage, have gotten smarter over the years.”

In both the Ohio and Texas cases, Kennedy voted with the conservative majority, so replacing Kennedy with Kavanaugh — who is Kennedy’s former law clerk — wouldn’t necessarily change the balance on the Supreme Court.

Those recent cases, combined with the closing of nearly 900 polling stations and purge of nearly 16 million voters from the rolls — a number of them purged incorrectly — between 2012 and 2016, increasing calls for stricter voter ID laws, elimination of early voting for workers with inflexible schedules, felon disenfranchisement — banning former felons from registering to vote — and a newly passed college student “poll tax,” have put voting rights advocates on alert, and vowing to make it an issue in Kavanaugh’s confirmation.

In 1999, as the Supreme Court was considering a challenge to Hawaii’s process for electing officials of the state Office of Hawaiian Affairs — only ethnic Polynesians were eligible to vote — Kavanaugh wrote an op-ed calling on the court to “adhere to the fundamental constitutional principle most clearly articulated by Justice Antonin Scalia: In the eyes of government, we are just one race here. It is American.”

Challengers argued the law was invalid under the 15th Amendment. But “there was a very specific discrimination against Native Hawaiians and a regime in the wake of that wanted to give them voting rights for a very specific purpose,” said Lucius. “[Kavanaugh] disregarded that and [showed] a lack of understanding about the rights of not just Indigenous people but other people who have suffered at the hands of government.”

Before the law was struck down by the Supreme Court 7-2 in an opinion delivered by Kennedy, Kavanaugh declared the case was a step toward an “inevitable conclusion within the next 10 to 20 years when the court says we are all one race in the eyes of government.”

By coincidence, if Kavanaugh is confirmed this year, his first term on the Supreme Court will be exactly 20 years after the Hawaii case was decided.

“Judge Kavanugh’s colorblind approach is a position fully at odds with the reality of ongoing racial discrimination that we have across our country today that manifests itself in the voting context,” said Kristen Clarke, president and executive director of the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law. “Voter suppression and racial gerrymandering remain alive and well. And there are no shortage of cases moving through the federal courts that make that clear. Judge Kavanaugh’s view raises grave concern about whether or not he would fully and fairly enforce our nation’s federal voting rights laws.”

More recently, in 2012, Kavanaugh sat on a three-judge panel ruling on a South Carolina voter identification law requiring registered voters to present a government-issued photo ID before they could cast their ballot. The law had been previously blocked by the Obama administration, which found that it would disenfranchise minority voters and violate the Voting Rights Act.

“The Justice Department did an investigation and found that black voters were significantly less likely to have the ID that the new state law required,” said Bains. “There are [tens of thousands of] registered voters who lack the required forms of ID, and all parties in the [South Carolina] case acknowledge that. And in that case, the court, with Kavanaugh writing for the court, upheld the law and approved its going into effect.”

In his opinion, Kavanaugh noted that “many states have enacted voter ID laws for the stated purposes of deterring voter fraud and enhancing citizens’ confidence in elections.” But “he didn’t give enough attention to the evidence of discriminatory intent,” said Bains about Kavanaugh, who also acknowledged that “minorities disproportionately lack photo IDs” and “the burden of obtaining a photo ID.”

While the panel’s decision was unanimous, Kavanaugh declined to sign a concurring opinion by the other two judges that cited “the vital function” the Voting Rights Act — which prohibits racial discrimination in voting — played in preventing an even stricter voter ID law.

“It’s a real dog whistle to those of us who pay attention to voting rights that Kavanaugh wouldn’t join a fellow Republican appointed judge in at least acknowledging the role that the Voting Rights Act plays in protecting voters before a discriminatory law goes into place,” said Lucius.

Meanwhile, Kavanaugh, outside of his judgeship, has acknowledged racial discrimination as a part of America’s reality. In a speech at a 2016 father-daughter Mass, he recommended the audience read one of his “all-time favorites, other than the Bible,” “To Kill a Mockingbird.” The book, Kavanaugh said, “forces you to confront the ugly history of racism in this country but also tells you about one of the key lessons a of life — to stand in someone else’s shoes to try to see things from their perspective.” Speaking at the White House event at which President Trump announced his nomination, Kavanaugh credited his mother, a former judge who taught at “two largely African-American public high schools in Washington, D.C.,” for teaching him “the importance of equality for all Americans.”

“The American people need to know where Judge Kavanaugh stands,” said Bains, referring to the nominee’s views on discrimination as it pertains to voting rights.

But others with a stake in the voter protection debate say Kavanaugh’s record is evidence enough. “In terms of where would Kavanaugh fit [on the Supreme Court], probably somewhere between Kennedy and the chief justice,” said Logan Churchwell, who is the spokesman for Public Interest Legal Foundation, a conservative group campaigning against voter fraud. “[Neil] Gorsuch was a total stealth candidate on voting rights. At least with Kavanaugh, we have the South Carolina case, and [that] case was a slam dunk by the time it was all said and done.”

If appointed, Kavanaugh will determine how the future Supreme Court decides voting rights cases, starting with a Wisconsin partisan gerrymandering case. Before the Supreme Court adjourned for the summer and Justice Kennedy announced his retirement, the justices in the Gill v. Whitford case unanimously rejected the challenge to legislative maps drawn in favor of Wisconsin GOP after the 2010 census. The justices sent the case back to district court due to lack of standing, giving the plaintiffs — 12 Wisconsin Democratic voters — a chance to re-argue their case.

“Odds are we should not see a big departure from what we saw in Gill this summer under Kavanaugh,” said Churchwell. “I don’t think anyone would disagree with that statement.”

Kavanaugh, according to a timeline issued by Senate Judiciary Committee Chairman Chuck Grassley, is expected to complete the confirmation process within 70 days.

_____

Read more from Yahoo News: