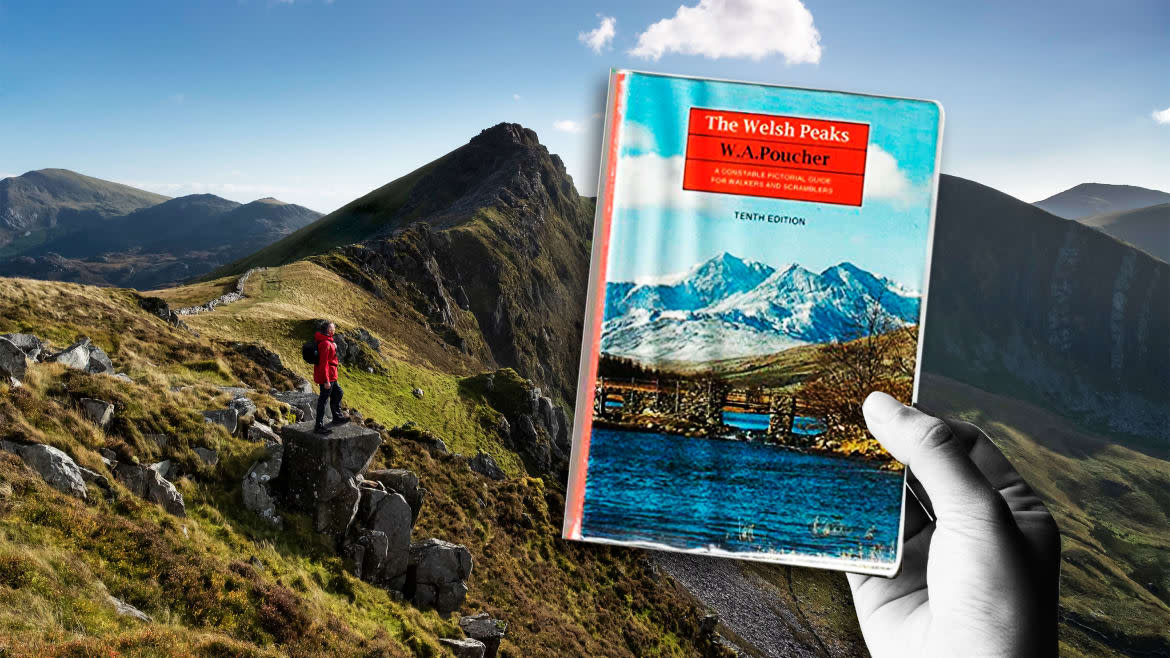

W.A. Poucher Helps You Climb Every Mountain From Your Couch. Start With “The Welsh Peaks” of Snowdonia.

Most of my books stand in disorderly piles, or haphazardly line shelves. But The Welsh Peaks by W.A. Poucher was, until the other day when I retrieved it to write this, in a drawer of treasured possessions. There are not many of those in my apartment. Like many émigrés, I packed light when I moved to America. This book, like old photographs and the scarf a very dear friend gave me, is one of those keepsakes that feels more necessity than whimsical.

This Mountain West Roadtrip Is One of America’s Most Underrated

The inscription, in my maternal grandmother’s writing, reads “April 1978,” with the words “Garndolbenmaen,” and a message of birthday wishes to my mother from my grandfather and grandmother. The book was first published in 1962, and this sixth edition was published by Constable in 1977. “Garndolbenmaen” is the name of the hamlet where we rented an isolated cottage for two weeks every Easter to climb the beautiful mountains of Snowdonia in Wales.

Time and wear has rendered the book cover-less, but I remember it showed Snowdon (in Welsh, “Yr Wyddfa”), the highest mountain in England and Wales (at 3,560 feet, 1,085 meters). It is one of those ’70s-typical technicolor images, richly colored with the greens of the hills, the greys of rock face and scree, drinkable blue skies, and wispy clouds kissing Snowdon’s peak, like cotton wool.

W.A. (William Arthur) Poucher, who wrote and photographed his walking adventures, would never use such language. The Welsh Peaks is not a flowery travel book. Poucher wrote this book for the dedicated walker out on the hills. Since the 1940s that is what he did, in Snowdonia, as well as the Lake District, the Scottish Highlands, the Peak District, the Isle of Skye, the Cairngorms, the Dolomites, Ireland, and the Surrey Hills of the English county of the same name—the closest of his adventures to his home in Reigate. He wrote walking books (and photographed them too) about all these places. He then shared his experiences in his practical, intimate books.

In The Welsh Peaks, the 56 mountain walk-routes Poucher talks about and photographs are so detailed that you know, rather than feel, that you are following in his footsteps. The routes Poucher lays out are multiple and detailed, crisply written and also idiosyncratic.

The black-and-white pictures—gorgeous interplays of light and shadow, sky and land mass—still delight me; the first is simply labeled “Tryfan in winter raiment,” and features two climbers gazing upon that mountain with its famous “Heather Terrace” thrown into relief by a winter blizzard.

The other images, like the first, are in black and white, and show beautiful panoramas, but with peaks named and black and white arrows pointing at things like cairns, or winding their way up the mountains to show you the way. There is a glossary of Welsh words, which explains the names of the hills all around you. Throughout, a simple R means right and L means left.

The names of the mountains and other landmarks are themselves immediate jolts of burnished memory; I can see their shapes and geography, at the same time as hearing their names again spoken from my parents’ lips: Cnicht (it really earns its nickname of “the Welsh Matterhorn”), Crib Goch, Glyder Fach, Carnedd Dafydd, Carnedd Llywelyn, the Cantilever (as magnificent as it sounds), Yr Aran, Moel Siabod, Llanberis, and Bristly Ridge (both mountain feature and perfect drag name).

Here is also Cadair Idris, Castell y Gwynt (Castle of the Wind), the Devil’s Kitchen, the Pyg Track, Glaslyn, Llyn Gwynant, Miners’ Track, Watkin Path, Ogwen Cottage, Llyn Ogwen, the standing “Adam and Eve” boulders on top of Tryfan (my mother’s favorite mountain—she had been evacuated to North Wales as a child), and Moel Hebog, a name that always elicited a young-boy giggle because “bog” is Brit-shorthand for the restroom.

This is a book for those who love mountain walking and the challenge and characters of mountains. The reason this book was in a treasured possessions’ drawer was that it survived countless treks up and down the mountains Poucher wrote about and we delighted in walking.

The book was packed in rucksacks that would also have contained Ordnance Survey maps, compasses, cagoule tops and bottoms wrapped up as tight cylinders, spare hats, gloves, and—best of all, for a little boy—packed lunches of sandwiches, Thermoses of sweet tea, chocolate biscuits, packets of Golden Wonder crisps, and fruit.

Always on Poucher-written walks, you reach somewhere where he had stood. You saw what he had written down. He could have been standing next to you. “Halt awhile,” he writes describing the climb to the peak of Carnedd Llywelyn, “on the rim of Craig yr Ysfa which discloses the vast Ampitheatre, hemmed in on either side by sheer cliffs that are the treasured playground of the rock climber.”

The writing is instructional for the walker, but it describes nature at its most beautiful, and so ascends to the majestic and lyrical, such as when he describes the many ways to tackle the Snowdon Horseshoe, the name given to the walk that encompasses Snowdon and the surrounding mountains Y Lliwedd, Garnedd Ugain, and Crib Goch.

The voice is knowledgeable, chatty-though-with-brevity, and notices everything. “The path is unmistakable and soon crosses a level green clearing containing the ruin of a hut, long ago used as a place of refreshment, after which it rises more steeply over rock and scree ultimately to thread the boulders scattered in profusion on the broad crest of Llechog.”

The book is not just a list of routes. Poucher also recommends the kind of clothes you should wear, the equipment you need, the best cameras, how to take photographs, how to find your routes in mist, and—the phenomenon that scared me the most when I read it as a boy—Brocken spectres, an optical illusion of a looming human form (yours) created by mist.

Poucher’s advice when it comes to the best boots remains true now as it ever has been: “Those who can afford the best will be amply repaid by their comfort and service through years of tough wear.” He has particular advice for the best soles for dry rock and wet rock.

For Poucher, climbing was serious, and it was vital that readers went out in preparation for all possible conditions. Many is the walk that starts out in sunshine and birdsong, and then, two thousand foot higher, suddenly you can be enveloped in mist and a storm. Poucher had been there too.

The book is as familiar to me as the roads between Garndolbenmaen and the nearest small town Porthmadog, and then the lovely road of dense forest and flirtatious mountain glimpses from Porthmadog to Beddgelert (named after the ill-fated hound Gelert), and then from Beddgelert to Capel Curig and Betws-y-Coed—always the best part of the journey because mid-way, the views opened up to the magnificent views of the Snowdon Horseshoe.

On every car-ride, there was such anticipation to see if Snowdon, our diva, would be in full view or obscured by cloud (still we would park the car, and pass the bags of crisps around; any mountain walker knows that rain and mist can still be beautiful).

Until I wrote this, I never realized that Poucher was one of the other guests on the infamous 1980 edition of Russell Harty’s BBC chat show when the host was physically attacked by Grace Jones for turning his back on her. I also had no idea Poucher was a perfumier, and appeared on that show in make-up and ladies’ gloves. Poucher was 89 at the time.

Indeed, Poucher, one realizes re-reading The Welsh Peaks, is a man of precisely enjoyed passions. Mountaineering, even when doing with other people, is solitary in the moment you are doing it, breath upon breath as you move higher, or look around; it acts upon your senses and yours alone, even if it is shared.

Reading Poucher now, it feels to me that he loved being out on the hills for the reason—I think—that we, and many others did. Yes, we wanted to get to the tops of all the mountains we set out to climb, for sure. Any walker bores of the ridges and twists and turns in the early and middle parts of a climb before increased height is attained and the views open up, and before that final exhilarating dash to a summit.

Poucher conveys all those moments cloaked in patient instruction, recommending one route up Snowdon is best attempted not in the crowded summer months (especially by those non-climbers who have taken the train up Snowdon), but “in early spring or late autumn when the profound solitude of this lofty ridge will act as balm to your soul.”

It wasn’t about “bagging” peaks for Poucher—and wow, he racked them up. It was the physical act of exertion, the finding shelter from a sudden storm in the lee of a cairn or natural outcrop, that thrilled him. It was knowing the hills closely, step by step, scramble by scramble, finding a safe shortcut, chancing upon a magnificent view. It was taking a moment when, the higher you went the sudden panorama of Snowdonia would open up, and even further to the Irish Sea and peaks in the North of England.

Sometimes, as a little boy, I remember being up so high on a mountain that you would be above the military jets which would occasionally zoom below you on training exercises, following the path of valleys out to RAF Anglesey. The sound they made was first a wrenching screech, and then—long past you—the landscape might echo to a sonic boom, which sounded like an angry clap of thunder.

We would marvel at those jets and their power, and yet we felt (absurdly) more powerful and invincible just by the fact of being above them. After they’d gone—Poucher’s book jostling in a rucksack next to a well-buttered cheese and tomato sandwich (with salad cream in those days, not mayonnaise), Thermos, and Ordnance Survey maps—we turned around to face the mountain in hand and carried on climbing towards our next peak.

Get our top stories in your inbox every day. Sign up now!

Daily Beast Membership: Beast Inside goes deeper on the stories that matter to you. Learn more.