In WA’s northern waters, Lummi keep sustainable, ancient salmon fishing techniques alive

The production of this article and accompanying photographs are the result of a collaboration between environment and science news platform, Mongabay, and McClatchy News.

“Some mornings, the sun’s hitting that reef net just right and it’s like I know it’s talking to me,” said Ellie Kinley, a member of the Lummi (Lhaq’temish) Nation and the last Indigenous permit holder of an ancient salmon fishing practice. Her reef net rig, parked on the shore of Lummi Nation Stommish grounds, serves as a reminder of a once-thriving Indigenous fishing tradition that, for now, sits idle. “It’s saying, ‘I’m sitting here. Don’t forget about me.’”

For centuries, Indigenous people of the Salish Sea relied on reef netting as a sustainable salmon fishing technique, but colonialism has left the tribes disconnected from a practice that once defined their cultural identity. Now, many find themselves balancing day-to-day economic realities with an ardent desire to revive reef net fishing and restore this vital link to what they say is their sacred heritage.

Reef net fishing intercepts chinook, coho, sockeye, chum and pink salmon as they travel from the Pacific Ocean to spawn in the Fraser River near present-day Washington state and British Columbia.

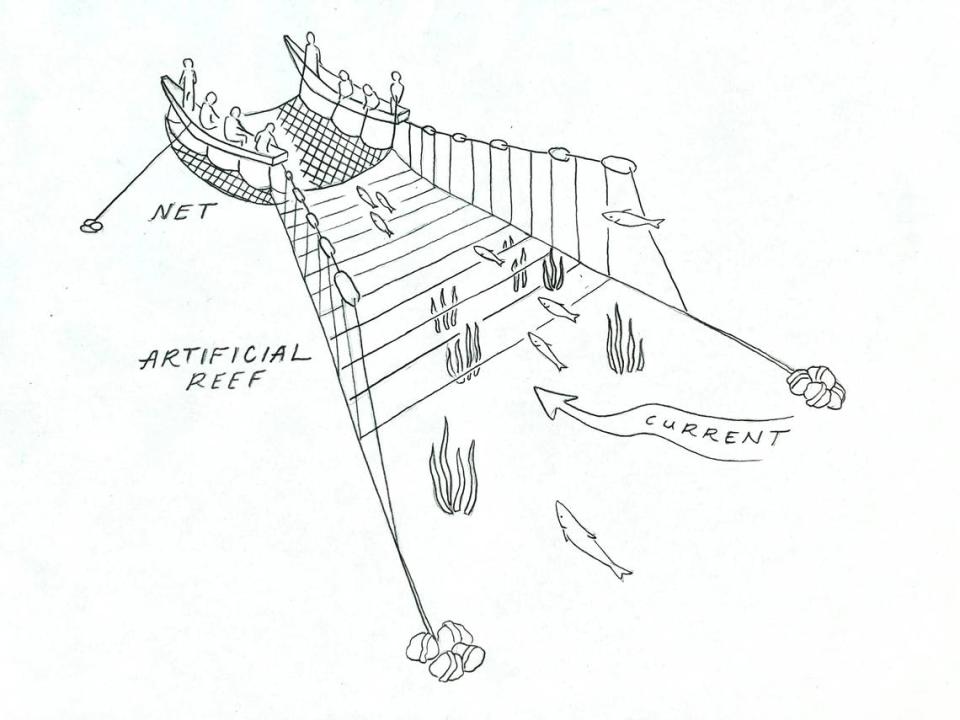

Rather than chasing the fish, this technique relies on a net stretched between two anchored boats. Long lines of rope run from the boats, creating an artificial reef that corrals the fish into the net. (Hence the name reef net). Once the salmon reach the net, the lookouts sound the alarm, and the crew quickly pulls the catch into the boat. Traditionally, Lummi built these rigs from cedar wood and fiber ropes and anchored the rigs along the salmons’ path using large boulders.

On the reef net, any non-target fish are tossed back into the water, resulting in almost no bycatch. In the old ways, a circular opening was built into the net to allow some salmon to pass through and continue their genetic line.

This ultra-selective and small batch harvesting method has been described as the most sustainable commercial salmon fishery practice. But for the Native people of the Salish Sea, a diverse group of independent nations with territories on both sides of the U.S.-Canadian border who created and perfected reef netting, the practice was more than a way to make money or even to put food on the table. For millennia, the reef net played a central role in their spirituality and community structure.

The reef netting technique

Lummi people passed reef net sites from generation to generation. “It was a private property right, not written down but passed like your bloodline,” Steve Solomon, a lifelong Lummi commercial fisherman and traditional knowledge holder of the reef net practice, told Mongabay. Many of the Lummi place names are tied to reef net sites, and “everyone in the village played some role in the harvest or preparation of salmon. Even the children and elders participated by praying in the salmon ceremonies.”

“As a knowledge system, the Reef Net in many ways defined our existence and relationship to our homelands, and to one another as a people, and as a nation,” Nicholas XEMŦOLTW̱ Claxton a member of the W̱SÁNEĆ a First Nations who neighbor the Lummi to the north, in modern day Canada, wrote in his doctoral dissertation on reef netting.

However, centuries of colonialism and fishing laws enacted by the US and Canadian governments separated Native people from the reef nets. Now, just 12 permits exist, and only one belongs to a member of the Lummi Nation. Ellie Kinley inherited that permit from her late husband, the highly respected Lummi elder and fisherman, Larry Kinley. This year, Ellie and her sons didn’t set the reef nets, saying it didn’t make sense financially.

In 2023, just 8 of the 12 permitted reef net rigs anchored in the Salish Sea. One of these is owned and run by Riley Starks, director of the Salish Center for Sustainable Fishing Methods, who has worked on reef nets in Legoe Bay off the shore of Lummi Island since 1991.

In mid-September, when Mongabay and McClatchy visited Riley’s rig, the crew was motley, composed of a couple of software engineers, a former puppeteer turned ferryman, and a farmer. Some said they worked other jobs to support their fishing habit.

The reef net is a peaceful operation, quiet enough to still hear the cows mooing from the shore — until the salmon come. The modern reef net rigs use underwater cameras, sonar and lookout towers to spot the fish. Once spotted, the rig uses solar-powered winches to lift the net, guided and assisted by the crew. Fish are quickly funneled into a holding pen alongside the boat, leaving them alive and immersed in seawater. Any unintended catch is thrown back to swim another day.

The 2023 salmon fishing season

Once it’s time to end the day’s fishing, a crewmember holds each live fish and rips one of its gills before placing it back in the holding pen. The fish bleed out swimming in the saltwater. The resulting fillets are pristine and command a premium price at market due to this handling and the high-fat content of the fish coming back from the cold ocean. But this year’s poor salmon runs show that salmon fishing can be an uncertain business.

“This year, Fraser River-origin sockeye and chum salmon came in quite poor and below the historical average,” Mickey Agha, statewide salmon science and policy analyst at the Washington Department of Fish & Wildlife, said in an interview. Pink salmon returned “well above expectations,” but the price was too low to make commercial fishing worthwhile. Like corn, wheat and oil, salmon is considered a commodity. Prices fluctuate with the market, and this year, prices bottomed out.

In a good year, reef nets can catch hundreds of salmon a day. One day this year, Riley’s crew caught only thirty fish, the next only 12, all pinks. Within a few weeks, they shut the operation down.

Lummi Island Wild, the largest commercial reef netting operation, didn’t set their rigs this year.

Lifelong fisherman Steve Thatcher’s rig scooped up just over 4,000 fish in eleven days. “It’s a terrible year,” he said, noting that some years they’ve brought in more than 20,000 salmon over just a few weeks. Still, Thatcher said, he goes out because he loves the reef net.

“Current reefnetters hold this practice very dear. Some of these guys are third-generation reefnetters,” Thatcher said. “The fleet is how it is today because of people who have fought for it at the political level and cared enough about it to be sure managers knew and understood how it worked.”

Preserving reef netting for all

Both native and non-native fishers Mongabay spoke with said there is room for Native and non-Native people to practice reef netting. “It’s not a competition,” Ellie said.

“In my mind, we are keeping the practice going until the Lummi are able to join,” Starks, of the Salish Center for Sustainable Fishing Methods, said.

More time in the water could make the reef nets commercially viable, but in response to salmon declines, “commercial fisheries have been reduced in recent years to allow as many fish as possible to reach the spawning grounds and to meet escapement targets,” salmon science and policy analyst Agha said. This includes reef nets.

Nowadays, when there are enough fish for the reef net to be in the water, Ellie said she and her two sons need to be out purse seining instead, a fishing method that follows the fish and uses a large net to scoop up everything that it surrounds. This method tends to be more profitable, but is not as selective.

“The big boat’s the only chance we have to make money,” Ellie said. “As a fisher that chases fish, it is really hard to go back to a set-in position, just hoping the fish come to you. That’s a real adjustment.”

The separation of the Lummi from the reef netting practice began with white settler colonialism, Lummi commercial fisherman Solomon said, and has a complex history. The 1855 Point Elliott Treaty brought a big change to the fishing landscape when it formalized fishing rights. The treaty did not “give” rights to the tribes, Solomon clarified, but rather formalized the rights they already had. It also extended rights to non-natives, who, in turn, began to encroach on Native traditional fishing grounds. In 1890s, the Alaska Packers company put fish traps in the path of Lummi reef nets, intercepting nearly all incoming fish and depriving Lummi of their catch. During this mass trapping era, many Lummi reef netting sites were also destroyed by white settlers including at Village Point on Lummi Island.

In 1987, reefnets were essentially outlawed. A new law stated that “fixed appliances” including reefnets, could not fish within the limits prescribed by law for the protection of the commercial fish traps.

“The state enforcement arm looked at all Indians as fishing criminals,” Solomon said. In response to violence and competition from trappers and fishing boats, Lummi communities adopted different techniques, such as purse seining and gillnetting, which they continue to this day.

Fish trappers continued to overharvest for decades until, in the name of conservation, Washington state officially outlawed all fish traps in 1934, including reef nets. A few years later, non-natives petitioned for an exemption to allow reef netting, which was granted. However, by this time the Lummi had been forced out of their traditional sites and non-native fishers had moved in.

Although the landmark Boldt Decision in 1974 affirmed the Lummi’s treaty rights to half the salmon catch, the ruling came after habitat loss, overfishing and pollution had already damaged salmon populations fishing laws had separated the tribes from the reef net.

“50% of nothing is nothing,” Solomon said.

The future of reef net fishing

In the U.S. Pacific Northwest 28 populations of salmon and steelhead are listed under the Endangered Species Act and around half of BC Pacific salmon populations are in decline.

The biggest threat to Fraser River-origin salmon today, Agha said, is a rapidly warming marine climate, which causes a lack of food resources and reduced survival. Additionally, droughts in the salmon’s freshwater habitat have reduced river flows to historic lows, causing mass die-offs on spawning grounds or isolating salmon so they can never reach their spawning grounds to lay eggs.

Some research indicates that salmon farming has also played a role in salmon declines by transmitting sea lice and viral loads to wild salmon, including juveniles as they exit from the mouth of the Fraser River into the Ocean. In February, Fisheries and Oceans Canadian Coast Guard announced their decision not to renew licenses for fifteen open-net pen Atlantic salmon farm sites in the Discovery Islands, stating that “many First Nations along the Fraser River were not able to access wild salmon needed to sustain their FSC [food social, and ceremonial] needs.”

But the salmon still stand a chance. “Researchers have identified that large-scale habitat protection and restoration are key factors to Fraser River-origin salmon recovery,” Agha said. Salmon need shade from vegetation along the streams and creeks where they come to spawn and where the young hatch and develop for months before heading back to sea.

Some of this restoration work is underway. The Nooksack Salmon Enhancement Association (NSEA), an NGO in Whatcom County, Washington, for example, plants vegetation to enhance river, creek and riparian habitat to reverse the trend of declining salmon runs.

For the Lummi Nation, who call themselves “salmon people,” the salmon decline has cut to the core of their cultural identity, said Solomon. “Without fishing, something is missing from our way of life.”

Some suggest subsidizing Indigenous participation in reef netting until the practice can support itself. In Italy, for example, the traditional Trabucco fisheries in the Adriatic Sea are subsidized by the government for their cultural and historical value and because they draw tourism and still provide some income.

“We don’t need to reinvent the wheel,” Solomon said. “The federal government already has farm and agriculture services… They just need to open those doors up to fishing. Reef netting should be on top of that list.”

“In the fishing industry, we all know how much the farmers are subsidized. And we’re left to starve some years,” Ellie said. “The only reason we’re starving is because of government decisions.”

As for the reef net, unpredictable and dwindling numbers of salmon, limits on fishing days, and a lack of workers make it an unreliable livelihood. And for some of the Lummi, sheer survival often forces focus away from preserving cultural practices.

Steve Solomon and his son, Troy Olson, another lifelong Lummi fisherman, said reviving reef net fishing is essential to restoring their cultural identity, the path towards cultural resurgence, and a path to sustainable salmon harvest. They hope to one day reestablish reef net fleets across their ancestral waters and teach new generations this sacred way of harvesting salmon.

This was also Larry Kinley’s vision. “His dream was to use it as a teaching platform, because it’s safe,” Ellie said. “He had really hoped that the Northwest Indian College would take it over…because there are generations who don’t know fishing at all, which makes me so sad. But everyone who goes out on the reef net falls in love with it. So, we need to get them out there… It’s their home and their heritage.”

For many in the Lummi Nation, reviving reef net fishing remains the vision, but the path there is still unclear. Until then, Ellie said she looks out at the rig in the mornings. “I know you’re there,” she said. “And I know I’ve got to continue that work. But for right now, I’ve got to make a living.”